1thorold

When I was one-and-twenty

I heard him say again,

“The heart out of the bosom

Was never given in vain;

’Tis paid with sighs a plenty

And sold for endless rue.”

And I am two-and-twenty,

And oh, ’tis true, ’tis true.

(A.E. Housman)

2thorold

Well, I used lines from that poem already last year, and I'm a little older than twenty-two by now, but you get the idea. Welcome to my first 2022 thread!

For those who don’t know me, I’m Mark, from The Hague, Netherlands (but with roots in the North of England). Hiker, occasional sailor, retired bureaucrat, and (currently) incompetent beginner at bookbinding. This will be my seventh year in Club Read, assuming I counted right.

My reading interests are difficult to predict, but often guided to some extent by the quarterly themes of Reading Globally: I'm leading the "Around the Indian Ocean" theme in Q1, so expect to see a lot of duplication between this thread and that one.

The 2021 threads are here:

Q1: https://www.librarything.com/topic/327713

Q2: https://www.librarything.com/topic/331117

Q3: https://www.librarything.com/topic/333425

Q4: https://www.librarything.com/topic/335663

For those who don’t know me, I’m Mark, from The Hague, Netherlands (but with roots in the North of England). Hiker, occasional sailor, retired bureaucrat, and (currently) incompetent beginner at bookbinding. This will be my seventh year in Club Read, assuming I counted right.

My reading interests are difficult to predict, but often guided to some extent by the quarterly themes of Reading Globally: I'm leading the "Around the Indian Ocean" theme in Q1, so expect to see a lot of duplication between this thread and that one.

The 2021 threads are here:

Q1: https://www.librarything.com/topic/327713

Q2: https://www.librarything.com/topic/331117

Q3: https://www.librarything.com/topic/333425

Q4: https://www.librarything.com/topic/335663

3thorold

2021 stats:

In Q4:

I finished 47 books in Q4 (Q1: 36, Q2: 43, Q3: 55).

Author gender: F: 15, M: 32 (68% M) (Q1: 66% M, Q2: 77% M, Q3 73% M)

Language: EN 27, NL 11, DE 5, FR 4 (57% EN) (Q1: 52% EN, Q2: 33% EN, Q3 51% EN)

Translations: 2 from Portuguese (1 to Dutch, 1 to French), 1 each from Croatian and Italian

2 books were related to the Q3 Lusophone theme, 3 to the "Translation prize winners" theme

Publication dates from 1859 to 2021, mean 1992, median 2005; 9 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 25, physical books from the TBR 8, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 4, audiobooks 0, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 5 — 17% from the TBR (Q1: 52%, Q2: 58%, Q3: 51% from the TBR)

37 unique first authors (1.3 books/author; Q1 1.2, Q2 1.1, Q3: 1.0)

By gender: M 29, F 8 : 78% M (Q1 70% M, Q2 77% M, Q3 72% M)

By main country: UK 10, NL 8, FR 3, DE 3, US 4, and various singletons

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

30/9/2020 : 94 books (89465 book-days) (Change: 39 read, 39 added)

31/12/2020: 90 books (79128 book-days) (Change: 31 read, 27 added)

2/4/2021: 101 books (84124 book-days) (change: 19 read, 30 added)

2/7/2021: 88 books (80882 book-days) (change: 25 read, 12 added)

01/10/2021: 89 books (69902 book-days) (change: 28 read, 29 added)

01/01/2022: 93 books (77389 book-days) (change: 8 read, 12 added)

The average days per book still on the pile is 832 (1172 at the end of 2019; 879 at the end of 2020; 833 at the end of Q1, 919 at end of Q2, 785 at the end of Q3). Obviously the splurging on library books after a long period of not using my library card took its toll...

2021 was a much more "normal" reading year for me than 2020. I'm not quite sure why, but it's probably reassuring to find that the infection rate of my library is not increasing monotonically. There does seem to be an odd sort of seven-year cycle going on, though. Check back at the start of 2029 to see whether this was just a freak.

In Q4:

I finished 47 books in Q4 (Q1: 36, Q2: 43, Q3: 55).

Author gender: F: 15, M: 32 (68% M) (Q1: 66% M, Q2: 77% M, Q3 73% M)

Language: EN 27, NL 11, DE 5, FR 4 (57% EN) (Q1: 52% EN, Q2: 33% EN, Q3 51% EN)

Translations: 2 from Portuguese (1 to Dutch, 1 to French), 1 each from Croatian and Italian

2 books were related to the Q3 Lusophone theme, 3 to the "Translation prize winners" theme

Publication dates from 1859 to 2021, mean 1992, median 2005; 9 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 25, physical books from the TBR 8, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 4, audiobooks 0, paid ebooks 5, other free/borrowed 5 — 17% from the TBR (Q1: 52%, Q2: 58%, Q3: 51% from the TBR)

37 unique first authors (1.3 books/author; Q1 1.2, Q2 1.1, Q3: 1.0)

By gender: M 29, F 8 : 78% M (Q1 70% M, Q2 77% M, Q3 72% M)

By main country: UK 10, NL 8, FR 3, DE 3, US 4, and various singletons

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

30/9/2020 : 94 books (89465 book-days) (Change: 39 read, 39 added)

31/12/2020: 90 books (79128 book-days) (Change: 31 read, 27 added)

2/4/2021: 101 books (84124 book-days) (change: 19 read, 30 added)

2/7/2021: 88 books (80882 book-days) (change: 25 read, 12 added)

01/10/2021: 89 books (69902 book-days) (change: 28 read, 29 added)

01/01/2022: 93 books (77389 book-days) (change: 8 read, 12 added)

The average days per book still on the pile is 832 (1172 at the end of 2019; 879 at the end of 2020; 833 at the end of Q1, 919 at end of Q2, 785 at the end of Q3). Obviously the splurging on library books after a long period of not using my library card took its toll...

2021 was a much more "normal" reading year for me than 2020. I'm not quite sure why, but it's probably reassuring to find that the infection rate of my library is not increasing monotonically. There does seem to be an odd sort of seven-year cycle going on, though. Check back at the start of 2029 to see whether this was just a freak.

4thorold

2022 plans

Well, there are a lot of things I could be reading in 2022, and probably a lot of other things I shall be reading that have nothing to do with any plans I might make. Some general lines, at least:

— the Reading Globally theme reads, especially the Indian Ocean in Q1

— the CR Victorian theme — I've started David Copperfield already

— the Dutch mega-novel Het Bureau, where I got up to the end of part 4/7 last year

— Toni Morrison: I started a read-through of her work last year but only got as far as Beloved before I was side-tracked

— that pesky TBR pile and its 93 books. Especially the two hefty leftovers from my 2020 Christmas books, plus The books of Jacob from Christmas 2021...

— my RL book-club, where we do still occasionally manage to finish a book

I just hope there aren't any more books about Neutral Moresnet. I'm fairly sure I've exhausted that topic by now...

Well, there are a lot of things I could be reading in 2022, and probably a lot of other things I shall be reading that have nothing to do with any plans I might make. Some general lines, at least:

— the Reading Globally theme reads, especially the Indian Ocean in Q1

— the CR Victorian theme — I've started David Copperfield already

— the Dutch mega-novel Het Bureau, where I got up to the end of part 4/7 last year

— Toni Morrison: I started a read-through of her work last year but only got as far as Beloved before I was side-tracked

— that pesky TBR pile and its 93 books. Especially the two hefty leftovers from my 2020 Christmas books, plus The books of Jacob from Christmas 2021...

— my RL book-club, where we do still occasionally manage to finish a book

I just hope there aren't any more books about Neutral Moresnet. I'm fairly sure I've exhausted that topic by now...

5Dilara86

Happy New Year! Your thread is always a pleasure to read, although not terribly good for keeping a manageable wishlist...

7labfs39

I'm looking forward to the Indian Ocean theme read. I'm not sure yet what I'll read and will key an eye on the thread for suggestions.

8SassyLassy

Happy New Year!

Given your amazing reading pace, wondering how long it will take until your first review!

Seriously, I'm looking forward as always to all of them

Given your amazing reading pace, wondering how long it will take until your first review!

Seriously, I'm looking forward as always to all of them

9arubabookwoman

Hello Mark, I will be following your reading with interest this year. I am always impressed by how many books you read, especially since so many of the are what I would describe as serious or difficult books. But I get lots of ideas here for my TBR or wishlist. Here's to a good reading year.

10thorold

>5 Dilara86:->9 arubabookwoman: Thanks all for the good wishes! I'll take your comments to heart and try to read more frivolous books in 2022 :-)

I came into 2022 partway through a long biography, so it may be a day or two before I post any reviews. But watch this space!

>1 thorold: Someone suggested that I should have chosen a photo with a French street name on it, in keeping with my subject-line. There doesn't seem to be anything really suitable in my photo stockpile. This could be another approach to infinite rue, perhaps:

I came into 2022 partway through a long biography, so it may be a day or two before I post any reviews. But watch this space!

>1 thorold: Someone suggested that I should have chosen a photo with a French street name on it, in keeping with my subject-line. There doesn't seem to be anything really suitable in my photo stockpile. This could be another approach to infinite rue, perhaps:

11baswood

Happy New Year Mark and good luck with the bookbinding. A dangerous occupation for an avid reader?

12NanaCC

>10 thorold: This picture and your comment made me smile. I’ll be following along, mostly lurking. You always have something of interest.

13dchaikin

Cool stats and impressed your TBR came down 12% over two years. I'm following again, of course. I've picked up a lot here over the last few years.

14lisapeet

I'm interested in bookbinding too, though not enough to have ever approached it in any organized way. I hope you post some pictures of projects. And Happy New Year!

15thorold

It's an unusually long time since I finished a book: 16 December was the last one. Various false starts, as well as seasonal distractions and the above-mentioned outbreak of bookbinding in my living room. There's a bookbinding post and a few pictures coming (>11 baswood:, >14 lisapeet:), but first it's about time for the first book of 2022, one of my Christmas books, and a follow-up to my reading about Beethoven and the Schumanns over the past few years:

Johannes Brahms : a biography (1997) by Jan Swafford (USA, 1946- )

Brahms is not the most obvious subject for a biography: he was a hard-working career musician, who put a lot of complexity into his music but kept his life almost ostentatiously simple. He was notoriously healthy, and never married or had a serious love-affair (plenty of flirtations, though, including one of forty years' duration with Clara Schumann). No-one has ever discovered any suggestion of him having sex with anyone other than a prostitute, but there's no mystery about the reasons for that: his experiences playing piano in sailors' dance-halls in Hamburg as a boy obviously left him with seriously distorted ideas about women and sexuality. But that's pretty much the only "dark spot" for biographers to illuminate, and it's soon dealt with.

Apart from that, there's the famous Brahmsians vs. Wagnerites divide that enlivened musical debate in the second half of the 19th century. Swafford has his fun with this, of course, but he also makes sure we understand that it was never quite as simple as that. Brahms himself was known to say positive things about Wagner's operas, and he owned a number of Wagner scores and knew them intimately. He often joked in later life that for an old man, the temptation to write operas was like the temptation to get married — he took care never to compete with Wagner on his own turf. There's also the bizarre way Brahms's (Jewish) former friend Hermann Levi became Wagner's preferred conductor after Hans von Bülow (whose wife had run away with Wagner) defected the other way to become the most respected interpreter of Brahms...

Even if his major works often took a while to work their way into the hearts of the public, Brahms was publishing a steady stream of stuff eminently suitable for middle-class people to play in their drawing-rooms or amateur choirs to sing, making him one of the first major composers to earn his living mostly from publications. Between the Wiegenlied ("Brahms's Lullaby") and the German Requiem, he pretty much offered a cradle-to-grave music service, with more Liebeslieder and Hungarian Dances than anyone could possibly want in between...

Swafford doesn't spend much time on this "mass-market" side of Brahms, but he does go into rewarding amounts of detail about the composition and reception of the symphonies, concertos and major chamber works. And that seems to be where this biography really scores: Swafford manages to make the mysterious and very technical process of composing music almost accessible for the non-musician. And that "almost" is only there because you do need at least a certain amount of background knowledge of music history and of basic concepts like forms and keys and time signatures to follow his explanations, without which you probably wouldn't be reading a book like this anyway.

The stress is on how Brahms built new and unexpected things on the existing structures of classical and romantic music: he was writing for a very informed public, and he took care to promote the wider understanding of music history, bringing out new editions of earlier composers and forcing the Viennese public to listen to Bach and Palestrina whether they liked it or not. Swafford credits Brahms with pushing through the switch in concert-hall repertoire from mostly contemporary programming — as it had been up to that point — to the canon-based programmes that still dominate things today. I suspect that's an exaggeration, but he obviously played a big part in making the listening public more aware that appreciating music implies knowing about where it comes from historically.

There are some minor things I don't like about the book: it's over-long, and Swafford repeats himself a lot when talking about non-musical background topics ("Ah yes, there's the "Antisemitism" theme from Chapter One again..."). And there's some carelessness about the use of idioms — it's not a good idea to fix in the reader's mind the image of Brahms putting failed works and early drafts "in the stove" to destroy them if you also talk about him putting pieces that need more refinement "back in the oven". But those are all very minor things, the point of this book is to talk about Brahms and his composition process and his relationships with his musical contemporaries, and that Swafford does extremely well.

Johannes Brahms : a biography (1997) by Jan Swafford (USA, 1946- )

Brahms is not the most obvious subject for a biography: he was a hard-working career musician, who put a lot of complexity into his music but kept his life almost ostentatiously simple. He was notoriously healthy, and never married or had a serious love-affair (plenty of flirtations, though, including one of forty years' duration with Clara Schumann). No-one has ever discovered any suggestion of him having sex with anyone other than a prostitute, but there's no mystery about the reasons for that: his experiences playing piano in sailors' dance-halls in Hamburg as a boy obviously left him with seriously distorted ideas about women and sexuality. But that's pretty much the only "dark spot" for biographers to illuminate, and it's soon dealt with.

Apart from that, there's the famous Brahmsians vs. Wagnerites divide that enlivened musical debate in the second half of the 19th century. Swafford has his fun with this, of course, but he also makes sure we understand that it was never quite as simple as that. Brahms himself was known to say positive things about Wagner's operas, and he owned a number of Wagner scores and knew them intimately. He often joked in later life that for an old man, the temptation to write operas was like the temptation to get married — he took care never to compete with Wagner on his own turf. There's also the bizarre way Brahms's (Jewish) former friend Hermann Levi became Wagner's preferred conductor after Hans von Bülow (whose wife had run away with Wagner) defected the other way to become the most respected interpreter of Brahms...

Even if his major works often took a while to work their way into the hearts of the public, Brahms was publishing a steady stream of stuff eminently suitable for middle-class people to play in their drawing-rooms or amateur choirs to sing, making him one of the first major composers to earn his living mostly from publications. Between the Wiegenlied ("Brahms's Lullaby") and the German Requiem, he pretty much offered a cradle-to-grave music service, with more Liebeslieder and Hungarian Dances than anyone could possibly want in between...

Swafford doesn't spend much time on this "mass-market" side of Brahms, but he does go into rewarding amounts of detail about the composition and reception of the symphonies, concertos and major chamber works. And that seems to be where this biography really scores: Swafford manages to make the mysterious and very technical process of composing music almost accessible for the non-musician. And that "almost" is only there because you do need at least a certain amount of background knowledge of music history and of basic concepts like forms and keys and time signatures to follow his explanations, without which you probably wouldn't be reading a book like this anyway.

The stress is on how Brahms built new and unexpected things on the existing structures of classical and romantic music: he was writing for a very informed public, and he took care to promote the wider understanding of music history, bringing out new editions of earlier composers and forcing the Viennese public to listen to Bach and Palestrina whether they liked it or not. Swafford credits Brahms with pushing through the switch in concert-hall repertoire from mostly contemporary programming — as it had been up to that point — to the canon-based programmes that still dominate things today. I suspect that's an exaggeration, but he obviously played a big part in making the listening public more aware that appreciating music implies knowing about where it comes from historically.

There are some minor things I don't like about the book: it's over-long, and Swafford repeats himself a lot when talking about non-musical background topics ("Ah yes, there's the "Antisemitism" theme from Chapter One again..."). And there's some carelessness about the use of idioms — it's not a good idea to fix in the reader's mind the image of Brahms putting failed works and early drafts "in the stove" to destroy them if you also talk about him putting pieces that need more refinement "back in the oven". But those are all very minor things, the point of this book is to talk about Brahms and his composition process and his relationships with his musical contemporaries, and that Swafford does extremely well.

16dchaikin

“notoriously healthy” :)

I don’t have to background concepts you mention, but I enjoyed your review and all this info on Brahms.

I don’t have to background concepts you mention, but I enjoyed your review and all this info on Brahms.

17SassyLassy

There's a week long bookbinding course here every summer, but each year it seems I am away or people are visiting. Each year I vow "next year". Maybe this is the one.

>15 thorold: Enjoyed the Brahms review. That is odd about "in the stove" vs "back in the oven" (surely it would be a stove top simmer instead), and there's not even the intervention of translation.

>15 thorold: Enjoyed the Brahms review. That is odd about "in the stove" vs "back in the oven" (surely it would be a stove top simmer instead), and there's not even the intervention of translation.

18thorold

>17 SassyLassy: In German it would be even worse, "stove" and "oven" would both be "Ofen".

Shades of the "often/orphan" joke in Pirates of Penzance...

Shades of the "often/orphan" joke in Pirates of Penzance...

19rocketjk

Belated Happy New Year. I look forward to this year's supply of interesting writing and reviews on your thread. Cheers.

20thorold

Second book of the new year, and the first for the Indian Ocean theme read — this is a paperback I picked up from a local Little Library, which has been on my TBR for a few months. I didn't notice it when I picked it up, but the back part of the book has got damp at some point, and the pages start being wrinkly and slightly discoloured just about the point where the Ibis puts to sea at last. Almost as though it was done by design..

Sea of poppies (2008) by Amitav Ghosh (India, 1956- )

A historical novel set in 1838, with the East India Company's lucrative opium trade stalled because of the frivolous objections of the Chinese government to the import of large quantities of addictive drugs. There are rumours that Lord Palmerston may be contemplating firm action to teach them the value of Free Trade, but that's for the later parts of the trilogy.

In this first part, Ghosh sets himself the task of getting a bunch of very diverse characters on to the schooner Ibis, sailing from Calcutta to Mauritius with a cargo of indentured labourers ("coolies", or girmitiyas). But he has a lot of scene-setting to do, and social and historical background to fill in, and after all it is a trilogy, so there's plenty of time, and the ship doesn't sail until about three-quarters of the way into the book anyway.

The book picks up a lot of the typical themes of 19th century adventure stories: disguises, rescues, accidents, orphans fending for themselves, people passing as other races or genders, cruel tyrants, pirates, prisons, shipboard floggings, and all the rest of it. There's even a widow rescued from her husband's funeral pyre in the nick of time, although sadly Ghosh forgets that you're supposed to do this from a hot-air balloon... But this isn't a pastiche of Kipling or Jules Verne: there's a hard modern edge to the threats that the characters face, and you know that it isn't necessarily all going to turn out right in the end. And, perhaps more to the point, there's a sharp postcolonial view of life that questions what it sees and doesn't allow the reader to slip automatically into identifying with the European characters.

Ghosh is evidently deeply in love with the languages of the period, from the bizarre Indianised English of the British (what would later be called Hobson-Jobson) and the peculiarities of nautical English and the very specific shipboard pidgin used to communicate between European officers and their multiracial "lascar" crew members. Not to mention Bengali, Hindi, Urdu, Bhojpuri, etc. His exploration of odd words and their origins is perhaps a distraction from the unfolding of the story, but it is a great part of the enjoyment of reading the book.

The only place where he strikes a slightly wrong note linguistically is in the character Paulette, whom he makes to speak an implausible Hercule Poirot sort of Franglais, to remind us how different she is in her background from the British around her. But she's also a clever teenage girl, who has grown up bilingual in Bengali and French, in a city where (Indian) English was being spoken all around her, and has lived in a British family for a year when we first meet her. Young people accommodate to the language around them very fast: there's no way she would still be saying "attend" for "wait" and "regard" for "look", entertaining though that is to read. She'd be much more likely to have picked up "have a dekko..."

Sample of Ghosh at his most linguistically over the top, making fun of the English in India:

Sea of poppies (2008) by Amitav Ghosh (India, 1956- )

A historical novel set in 1838, with the East India Company's lucrative opium trade stalled because of the frivolous objections of the Chinese government to the import of large quantities of addictive drugs. There are rumours that Lord Palmerston may be contemplating firm action to teach them the value of Free Trade, but that's for the later parts of the trilogy.

In this first part, Ghosh sets himself the task of getting a bunch of very diverse characters on to the schooner Ibis, sailing from Calcutta to Mauritius with a cargo of indentured labourers ("coolies", or girmitiyas). But he has a lot of scene-setting to do, and social and historical background to fill in, and after all it is a trilogy, so there's plenty of time, and the ship doesn't sail until about three-quarters of the way into the book anyway.

The book picks up a lot of the typical themes of 19th century adventure stories: disguises, rescues, accidents, orphans fending for themselves, people passing as other races or genders, cruel tyrants, pirates, prisons, shipboard floggings, and all the rest of it. There's even a widow rescued from her husband's funeral pyre in the nick of time, although sadly Ghosh forgets that you're supposed to do this from a hot-air balloon... But this isn't a pastiche of Kipling or Jules Verne: there's a hard modern edge to the threats that the characters face, and you know that it isn't necessarily all going to turn out right in the end. And, perhaps more to the point, there's a sharp postcolonial view of life that questions what it sees and doesn't allow the reader to slip automatically into identifying with the European characters.

Ghosh is evidently deeply in love with the languages of the period, from the bizarre Indianised English of the British (what would later be called Hobson-Jobson) and the peculiarities of nautical English and the very specific shipboard pidgin used to communicate between European officers and their multiracial "lascar" crew members. Not to mention Bengali, Hindi, Urdu, Bhojpuri, etc. His exploration of odd words and their origins is perhaps a distraction from the unfolding of the story, but it is a great part of the enjoyment of reading the book.

The only place where he strikes a slightly wrong note linguistically is in the character Paulette, whom he makes to speak an implausible Hercule Poirot sort of Franglais, to remind us how different she is in her background from the British around her. But she's also a clever teenage girl, who has grown up bilingual in Bengali and French, in a city where (Indian) English was being spoken all around her, and has lived in a British family for a year when we first meet her. Young people accommodate to the language around them very fast: there's no way she would still be saying "attend" for "wait" and "regard" for "look", entertaining though that is to read. She'd be much more likely to have picked up "have a dekko..."

Sample of Ghosh at his most linguistically over the top, making fun of the English in India:

The unexpected dinner invitation from the budgerow started Mr Doughty off on a journey of garrulous reminiscence. ‘Oh my boy!’ said the pilot to Zachary, as they stood leaning on the deck rail. ‘The old Raja of Raskhali: I could tell you a story or two about him - Rascally-Roger I used to call him!’ He laughed, thumping the deck with his cane. ‘Now there was a lordly nigger if ever you saw one! Best kind of native - kept himself busy with his shrub and his nautch-girls and his tumashers. Wasn’t a man in town who could put on a burrakhana like he did. Sheeshmull blazing with shammers and candles. Paltans of bearers and khidmutgars. Demijohns of French loll-shrub and carboys of iced simkin. And the karibat! In the old days the Rascally bobachee-connah was the best in the city. No fear of pishpash and cobbily-mash at the Rascally table. The dumbpokes and pillaus were good enough, but we old hands, we’d wait for the curry of cockup and the chitchky of pollock-saug. Oh he set a rankin table I can tell you - and mind you, supper was just the start: the real tumasher came later, in the nautch-connah. Now there was another chuckmuck sight for you! Rows of cursies for the sahibs and mems to sit on. Sittringies and tuckiers for the natives. The baboos puffing at their hubble-bubbles and the sahibs lighting their Sumatra buncuses. Cunchunees whirling and tickytaw boys beating their tobblers. Oh, that old loocher knew how to put on a nautch all right! He was a sly little shaytan too, the Rascally-Roger: if he saw you eyeing one of the pootlies, he’d send around a khidmutgar, bobbing and bowing, the picture of innocence. People would think you’d eaten one too many jellybees and needed to be shown to the cacatorium. But instead of the tottee-connah, off you’d go to a little hidden cumra, there to puckrow your dashy. Not a memsahib present any the wiser - and there you were, with your gobbler in a cunchunee’s nether-whiskers, getting yourself a nice little taste of a blackberry-bush.’ He breathed a nostalgic sigh. ‘Oh they were grand old gollmauls, those Rascally burrakhanas! No better place to get your tatters tickled.’

Zachary nodded, as if no word of this had escaped him.

21labfs39

>20 thorold: Great review, Mark. I enjoyed Sea of Poppies when I read it a few years ago. Will you continue with the next one? I read the second, but not the third. Thank you for typing in the long passage. What a hoot!

22dchaikin

>20 thorold: I admit Ghosh didn't pull me into the sequel, but I remember the play with the language, which was great fun. Fun review, and, well, crazy quote.

23lilisin

>15 thorold:

I play as a violinist in an amateur orchestra and our April (spring) concert includes Brahm's 1st symphony, and his Tragic Overture. I'm playing 1st violin and 2nd violin respectively and boy is he hard to play. Maybe if he had flirted around a bit more he would have loosened up a little bit with his composing and allowed us violins a little rest for our fingers here and there. So hard!

I play as a violinist in an amateur orchestra and our April (spring) concert includes Brahm's 1st symphony, and his Tragic Overture. I'm playing 1st violin and 2nd violin respectively and boy is he hard to play. Maybe if he had flirted around a bit more he would have loosened up a little bit with his composing and allowed us violins a little rest for our fingers here and there. So hard!

24thorold

>23 lilisin: I can imagine! It was partly through the comments of a violinist friend that I started listening to Brahms more attentively.

Swafford talks a lot about Brahms’s long friendship with Joseph Joachim — apparently Joachim often had to read him the riot act about the unreasonable things he was asking string players to do, but it didn’t always help.

Swafford talks a lot about Brahms’s long friendship with Joseph Joachim — apparently Joachim often had to read him the riot act about the unreasonable things he was asking string players to do, but it didn’t always help.

25Dilara86

Having just read your answer to Question for the Avid Reader #2, I thought I'd tell you about a new book I've just reserved at the library (but haven't read yet!) called Rabalaïre that centers around a bicycling anti-hero. Here's the start of Marguerite Beaux's review:

Vous connaissez l’expression « avoir un petit vélo dans la tête » ? Elle ne saurait mieux s’appliquer qu’à « Rabalaïre », le nouveau roman massif, obsessionnel et totalement addictif du réalisateur Alain Guiraudie. Le narrateur, Jacques, est un quadragénaire homosexuel qui met à profit son chômage en faisant du vélo, en quête de beaux paysages et de rencontres. Un « rabalaïre », comme on dit en occitan : un type sans attaches, qui arrive d’on ne sait où, s’incruste un peu et puis repart.

26thorold

>25 Dilara86: Mmm. Tempting. But 1040 pages long…. Just what I don’t need right now.

28LolaWalser

>20 thorold:

Reading that para and what you say about the linguistic fireworks, I couldn't help flashing back to the strange and sly All about H. Hatterr--any chance you read it? It's just that it appears as if it may be an almost complementary piece to your book. Instead of the "Indianised British" there is the Anglicised Indian, Mr. Hatterr, whose language is no less baroque than that example but in the opposite direction.

Reading that para and what you say about the linguistic fireworks, I couldn't help flashing back to the strange and sly All about H. Hatterr--any chance you read it? It's just that it appears as if it may be an almost complementary piece to your book. Instead of the "Indianised British" there is the Anglicised Indian, Mr. Hatterr, whose language is no less baroque than that example but in the opposite direction.

29Dilara86

>26 thorold: Oh dear! I hadn't noticed the page count when I ordered it :-( And I've just started the collected works of Louis Guilloux - that's a 1114-page doorstop! Now I understand why it was available straight away despite featuring in the new acquisition highlights.

30thorold

>28 LolaWalser: No, I didn’t know about that, but it sounds interesting, especially with Salman Rushdie’s comment that Narayan and Desani are the Richardson and Sterne (respectively) of Indian literature…

All that history of loving baroque language is probably also a clue to why P G Wodehouse is so popular in India.

All that history of loving baroque language is probably also a clue to why P G Wodehouse is so popular in India.

31thorold

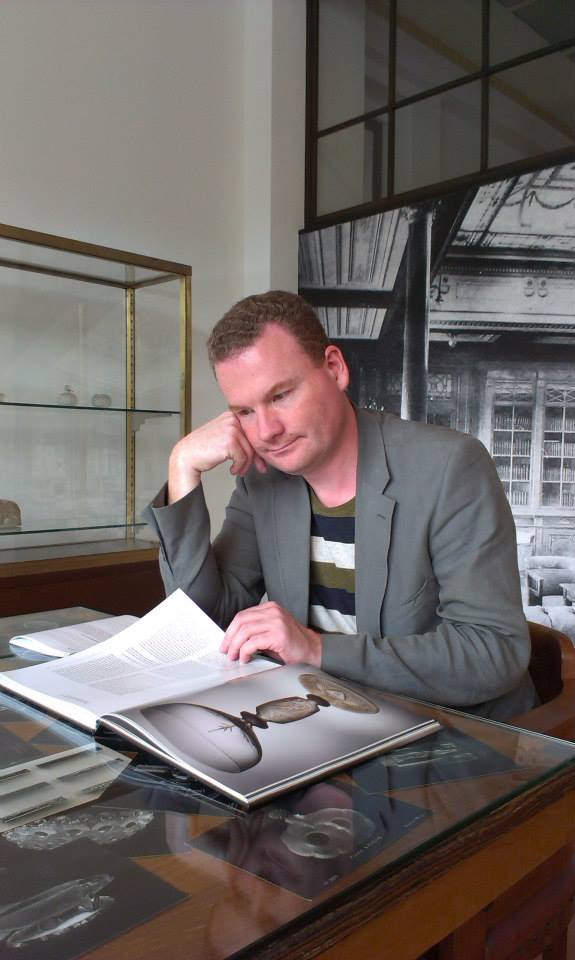

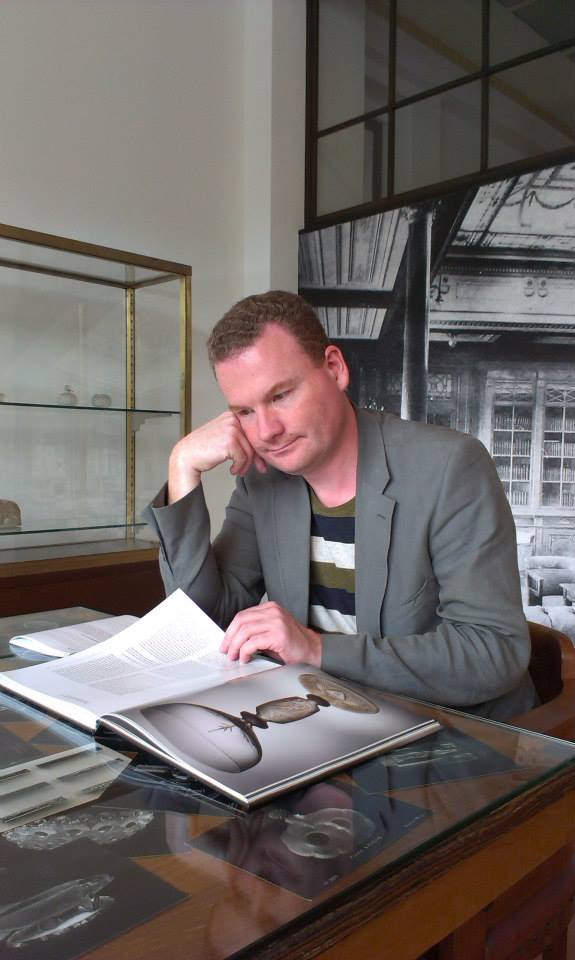

The next book seems to need a bit of introduction, because it's very closely linked with my current obsession with bookbinding. If you just want the review, skip to the next post.

I first came across French art historian Henry Havard (1838-1921) a few years ago, through a new Dutch translation of his travel book describing a summer holiday cruise around the Dead cities of the Zuiderzee. He wrote this in 1874, during a period when he was living as a political exile in the Netherlands, and it was an instant bestseller, rapidly translated into Dutch, English and German, and together with its two sequels it's credited with giving a major boost to the nascent Dutch tourist industry.

I was very interested to read what he had to say about the country as it was in the 1870s, and I looked around for a copy of the three books in the original French. All I was able to come up with inexpensively at the time, however, was a rather sorry-looking set still in the original publisher's temporary paper binding, liable to fall apart if you so much as looked at them.

I couldn't actually read them like that, so I ended up reading the second and third books as pdf's from archive.org

But I kept the idea in mind that I was going to do something to give the old books a useful life. I even had a recommendation from a friend of a local bookbinder who had done a good job for him on a similar project, but I somehow never got around to following that up.

Recently, with the combination of lockdowns and winter weather, I decided I would like to have a go myself. Apart from the Havard project, I have quite a few battered old books on my shelves that could do with a bit of repair, but certainly aren't valuable enough to justify paying someone to work on them. And I have a lot of journal issues in cardboard storage boxes that could do with binding...

YouTube didn't exactly make it look easy, but it did make it intelligible, and it looked as though you could get somewhere without needing to invest in a lot of fancy equipment. I found these two channels particularly helpful (both from the Southern Hemisphere, oddly enough):

https://www.youtube.com/c/DASBookbinding

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCVummyss9psNW1k1w4E2IuQ

There's a lot more out there that could be relevant, of course, but a lot of what comes up when you search for "bookbinding" is more about creating interesting craft projects than about making or repairing actual functional books. I also read a couple of classic textbooks, The art of bookbinding (1880) by Joseph William Zaehnsdorf, and Bookbinding and the care of books (1901) by Douglas Cockerell.

From there it was a short step to trying it out! Most of the tools you need are things you already have (cutting-mat, knives, glue, needle and thread, awl, rulers, etc.), and most of the supplies are things you can get from shops that sell artists' materials. It turns out that I also have a specialist stationer quite nearby who stocks book cloth, grey board, and all sorts of fancy papers — and was even happy to drop an order off at my front door during lockdown. The only scarce and exotic things you need, really, are presses for holding the work and for squishing it flat: proper bookbinding presses are things you would either need to find secondhand or commission from a craftsman, but in practice you can manage with boards, clamps, and heavy weights.

My sewing set-up vs. Cockerell's. I still have to work on that "harpist" pose!

I got started on a few small projects where I couldn't do any real harm if it all went wrong: I made a new case for a dictionary that had lost its spine long ago and was on the point of losing its covers as well, I bound some old journals from the 1970s, and so on. I was quite pleased to find that I could produce books that seemed perfectly robust and functional, even if they were by no means perfect — it obviously needs experience to judge the right width for the spine and the amount of "square" in the boards.

That gave me the courage to tackle the Havard books. It didn't go completely straightforwardly, in particular dismantling the original bindings without further damaging the old paper was quite tricky, and I had to do a certain amount of repair. I wouldn't advise anyone to try this on books that are of any real value. But the binding part was fine, and I ended up with three quite pleasant (if still slightly clumsy) matching bindings:

I've also been busy with my stock of journals. I've gone into a kind of mass-production mode there, with about fifty volumes bound to date and another twenty or so I'd like to do. Instead of a full case-binding, I'm doing these in the same style the bindery at work used to use, with a flexible cloth spine ("simplified German binding"). I've got some volumes saved from recycling that were bound that way in the thirties, so I'm assuming it will be more than durable enough for a personal library.

I first came across French art historian Henry Havard (1838-1921) a few years ago, through a new Dutch translation of his travel book describing a summer holiday cruise around the Dead cities of the Zuiderzee. He wrote this in 1874, during a period when he was living as a political exile in the Netherlands, and it was an instant bestseller, rapidly translated into Dutch, English and German, and together with its two sequels it's credited with giving a major boost to the nascent Dutch tourist industry.

I was very interested to read what he had to say about the country as it was in the 1870s, and I looked around for a copy of the three books in the original French. All I was able to come up with inexpensively at the time, however, was a rather sorry-looking set still in the original publisher's temporary paper binding, liable to fall apart if you so much as looked at them.

I couldn't actually read them like that, so I ended up reading the second and third books as pdf's from archive.org

But I kept the idea in mind that I was going to do something to give the old books a useful life. I even had a recommendation from a friend of a local bookbinder who had done a good job for him on a similar project, but I somehow never got around to following that up.

Recently, with the combination of lockdowns and winter weather, I decided I would like to have a go myself. Apart from the Havard project, I have quite a few battered old books on my shelves that could do with a bit of repair, but certainly aren't valuable enough to justify paying someone to work on them. And I have a lot of journal issues in cardboard storage boxes that could do with binding...

YouTube didn't exactly make it look easy, but it did make it intelligible, and it looked as though you could get somewhere without needing to invest in a lot of fancy equipment. I found these two channels particularly helpful (both from the Southern Hemisphere, oddly enough):

https://www.youtube.com/c/DASBookbinding

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCVummyss9psNW1k1w4E2IuQ

There's a lot more out there that could be relevant, of course, but a lot of what comes up when you search for "bookbinding" is more about creating interesting craft projects than about making or repairing actual functional books. I also read a couple of classic textbooks, The art of bookbinding (1880) by Joseph William Zaehnsdorf, and Bookbinding and the care of books (1901) by Douglas Cockerell.

From there it was a short step to trying it out! Most of the tools you need are things you already have (cutting-mat, knives, glue, needle and thread, awl, rulers, etc.), and most of the supplies are things you can get from shops that sell artists' materials. It turns out that I also have a specialist stationer quite nearby who stocks book cloth, grey board, and all sorts of fancy papers — and was even happy to drop an order off at my front door during lockdown. The only scarce and exotic things you need, really, are presses for holding the work and for squishing it flat: proper bookbinding presses are things you would either need to find secondhand or commission from a craftsman, but in practice you can manage with boards, clamps, and heavy weights.

My sewing set-up vs. Cockerell's. I still have to work on that "harpist" pose!

I got started on a few small projects where I couldn't do any real harm if it all went wrong: I made a new case for a dictionary that had lost its spine long ago and was on the point of losing its covers as well, I bound some old journals from the 1970s, and so on. I was quite pleased to find that I could produce books that seemed perfectly robust and functional, even if they were by no means perfect — it obviously needs experience to judge the right width for the spine and the amount of "square" in the boards.

That gave me the courage to tackle the Havard books. It didn't go completely straightforwardly, in particular dismantling the original bindings without further damaging the old paper was quite tricky, and I had to do a certain amount of repair. I wouldn't advise anyone to try this on books that are of any real value. But the binding part was fine, and I ended up with three quite pleasant (if still slightly clumsy) matching bindings:

I've also been busy with my stock of journals. I've gone into a kind of mass-production mode there, with about fifty volumes bound to date and another twenty or so I'd like to do. Instead of a full case-binding, I'm doing these in the same style the bindery at work used to use, with a flexible cloth spine ("simplified German binding"). I've got some volumes saved from recycling that were bound that way in the thirties, so I'm assuming it will be more than durable enough for a personal library.

32thorold

All of which brings me to Henry Havard again. Whilst I was busy with his books about the Netherlands, I found that he'd also written a book about Flanders. I downloaded a facsimile of that from archive.org as well, but instead of reading it as a pdf on my e-reader, I had the mad idea of creating an extremely labour-intensive and unnecessarily costly print-on-demand version. After all, up until then everything I'd bound had been something I'd already read...

I cleaned up the pdf in ScanTailor, printed out the 420 pages on nice paper using a booklet creator utility to get them in the right order for folding, stitched the sections together and bound them to match the three Dutch books.

The result isn't bad, and was quite agreeable to read, even with the slight fuzziness you get from scan + print (I scaled the print up from the original about 10%). Obviously pointless in all sorts of ways, but quite fun to do once in a while.

So, what about the contents of the book?

La terre des Gueux. Voyage dans la Flandre flamingante (1879) by Henry Havard (France, 1838-1921)

Imagine a travel book about Flanders. It will certainly talk about bicycle-racing, beer, bandes-dessinées, surrealism, art nouveau, the Congo, and the First World War, won't it? What else is there?

Now try to imagine that book as it might have been written in the 1870s...

Havard's approach to Flanders is a little bit different from the line he takes in his three Dutch books: this doesn't really pretend to be an account of a specific journey, and there's a lot less direct description of the author's subjective experience. And he didn't have his artist-friends with him, so there are no illustrations. But there's still a lot of colourful anecdote, a lot of it from the medieval period — Havard clearly enjoys nothing more than a good Burgundian story, and regards Charles V and Philip II as the spoilsports who put an end to the really colourful phase of European history. There are some entertaining digressions where he lays into the Belgian clergy whilst pretending to praise their work, and there's a general theme of the opposition between the liberal, enlightened capitalism of the Flemish towns and the conservatism and superstition of the countryside that he sees as the defining element in Flemish history. The book takes its title from the name (Gueux/Geuzen: "beggars") ironically adopted by the 16th century rebels against Spanish authority, revived in the 1870s by Havard's contemporaries in the Flemish liberal movement.

He starts out with Ypres and West Flanders, and slowly works across to cover Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp in the closing chapters. Typically for him, he spends most time on less well-known places like Veurne and Nieuwpoort, and in the three main cities he refers us to other books for the "obvious" stuff and focuses on things he happened to notice (...usually in old manuscripts in the municipal archives) that we probably don't know about. There's a lot about the destructive armed conflicts between neighbouring towns or between trades in the same town, about the complicated relationship between the towns and their (nominal) feudal overlords, but also about the modern traces of medieval institutions like the guilds of crossbowmen and the chambers of rhetoric.

Fun, if you like that sort of thing.

I cleaned up the pdf in ScanTailor, printed out the 420 pages on nice paper using a booklet creator utility to get them in the right order for folding, stitched the sections together and bound them to match the three Dutch books.

The result isn't bad, and was quite agreeable to read, even with the slight fuzziness you get from scan + print (I scaled the print up from the original about 10%). Obviously pointless in all sorts of ways, but quite fun to do once in a while.

So, what about the contents of the book?

La terre des Gueux. Voyage dans la Flandre flamingante (1879) by Henry Havard (France, 1838-1921)

Imagine a travel book about Flanders. It will certainly talk about bicycle-racing, beer, bandes-dessinées, surrealism, art nouveau, the Congo, and the First World War, won't it? What else is there?

Now try to imagine that book as it might have been written in the 1870s...

Havard's approach to Flanders is a little bit different from the line he takes in his three Dutch books: this doesn't really pretend to be an account of a specific journey, and there's a lot less direct description of the author's subjective experience. And he didn't have his artist-friends with him, so there are no illustrations. But there's still a lot of colourful anecdote, a lot of it from the medieval period — Havard clearly enjoys nothing more than a good Burgundian story, and regards Charles V and Philip II as the spoilsports who put an end to the really colourful phase of European history. There are some entertaining digressions where he lays into the Belgian clergy whilst pretending to praise their work, and there's a general theme of the opposition between the liberal, enlightened capitalism of the Flemish towns and the conservatism and superstition of the countryside that he sees as the defining element in Flemish history. The book takes its title from the name (Gueux/Geuzen: "beggars") ironically adopted by the 16th century rebels against Spanish authority, revived in the 1870s by Havard's contemporaries in the Flemish liberal movement.

He starts out with Ypres and West Flanders, and slowly works across to cover Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp in the closing chapters. Typically for him, he spends most time on less well-known places like Veurne and Nieuwpoort, and in the three main cities he refers us to other books for the "obvious" stuff and focuses on things he happened to notice (...usually in old manuscripts in the municipal archives) that we probably don't know about. There's a lot about the destructive armed conflicts between neighbouring towns or between trades in the same town, about the complicated relationship between the towns and their (nominal) feudal overlords, but also about the modern traces of medieval institutions like the guilds of crossbowmen and the chambers of rhetoric.

Fun, if you like that sort of thing.

33labfs39

>31 thorold: >32 thorold: Fascinating! Thank you for sharing. I will probably never try it myself, but I loved hearing about your experiences and seeing the photos. Keep us posted!

34LolaWalser

New level achieved, you're reading books you've published & bound yourself! The bindings look great, the text blocks are perfectly lined... very nice job.

36lisapeet

Very cool. I've always been interested in the mechanics of bookbinding but never actually got into the act itself.

37raton-liseur

What a nice hobby! I don't think I would be brave enough to do the same, but it seems a lot of fun (and patience)!

38rhian_of_oz

>31 thorold: >32 thorold: I think this is super cool, thanks for sharing.

39thorold

>33 labfs39: - >38 rhian_of_oz: Thanks, all! At the level where I am it is mostly patience, really — most of the individual steps aren't that difficult, but there are a lot of them, and a lot of that is repetitive stuff.

Something completely different: a book I came across whilst looking for something else, and picked up more as a reference book than to read from cover to cover:

Toutes les lignes & les gares de France en cartes: L'annuaire Pouey de 1933 (2019) by Clive Lamming (France, 1938- )

(Author picture from French Wikipedia)

The Pouey company, founded in the 1880s by a former employee of the Midi railway, filled a gap in the French market of the time by publishing a useful business handbook to freight tariffs. These annual handbooks are prized by modern historians because of the accurate, very up-to-date maps of the French railway system they contained.

Clive Lamming has put together this reprint of the maps for each Département from the 1933 edition of Pouey, each reproduced with a summary on the facing page of the situation in the Département and the changes (closures) that have taken place there since 1933. The maps are reproduced in colour, but reduced from the original to fit on an A4 page, and they are at the limit of legibility. All the same, there's a lot of very interesting information here about railways that have long-since disappeared: I'm sure this is something I'll often be referring to.

Something completely different: a book I came across whilst looking for something else, and picked up more as a reference book than to read from cover to cover:

Toutes les lignes & les gares de France en cartes: L'annuaire Pouey de 1933 (2019) by Clive Lamming (France, 1938- )

(Author picture from French Wikipedia)

The Pouey company, founded in the 1880s by a former employee of the Midi railway, filled a gap in the French market of the time by publishing a useful business handbook to freight tariffs. These annual handbooks are prized by modern historians because of the accurate, very up-to-date maps of the French railway system they contained.

Clive Lamming has put together this reprint of the maps for each Département from the 1933 edition of Pouey, each reproduced with a summary on the facing page of the situation in the Département and the changes (closures) that have taken place there since 1933. The maps are reproduced in colour, but reduced from the original to fit on an A4 page, and they are at the limit of legibility. All the same, there's a lot of very interesting information here about railways that have long-since disappeared: I'm sure this is something I'll often be referring to.

40dchaikin

Love your book binding and obscure reading. The whole description of book binding was fascinating to me, and I appreciate the pictures.

41NanaCC

Thank you for sharing your book binding experience. Very interesting along with the pictures. You will have to let us know when you’ve mastered the “harpist pose”. :-)

42baswood

>31 thorold: and >32 thorold: Good job. Standing back in admiration to your giving life back to old books.

43lilisin

Fascinating posts about book binding!

I certainly could use you for my copy of Balzac's Old Goriot. Although I don't think it needs anything more than a re-glue but the spine is falling off and I have to be careful with how I hold it as I read so it doesn't completely fall apart. The pages do seem to still be connected by the binding string though.

I certainly could use you for my copy of Balzac's Old Goriot. Although I don't think it needs anything more than a re-glue but the spine is falling off and I have to be careful with how I hold it as I read so it doesn't completely fall apart. The pages do seem to still be connected by the binding string though.

44thorold

>43 lilisin: If you want to try, search for “book repair” on YouTube, and you’ll find some useful demonstrations by librarians of how to deal with books that are falling apart. (But bear in mind that they are librarians, and thus have absolutely no scruples when it comes to being violent with books…)

45thorold

This was a spur of the moment purchase at the Gare du Nord last year, mostly because I was intrigued by the apparent incongruity of the eye-catching flowery cover (by Aline Zalko) on what was evidently a crime novel.

It's a cliché that you know you're getting old when the policemen start looking young, but it's even worse when you learn that that traumatic event in the policeman's distant past happened in the year 2000...

Claire Berest seems to be best-known for Gabriële, a book about their great-grandmother the Dadaist artist Gabriële Buffet-Picabia she co-wrote with her sister Anne Berest, but she's also written several novels independently since 2011.

Artifices (2021) by Claire Berest (France, 1982- )

(author photo French Wikipedia)

Abel Bac is a police officer with an impeccable twenty-year service record, no known vices and no private life to speak of. But he does seem to have a weak spot in the distant recesses of his adolescent memories, and there's someone out there who knows about it and is pressing on it hard, putting Abel's mental health — and his career — in peril. Not such an unusual scenario for a crime story, perhaps, except that the torture is inflicted in this case by means of highly sophisticated conceptual art installations, which all seem to be riffing in obscure fashion off a La Fontaine fable.

As a crime story it's a bit too straightforward and tightly plotted, without much room for mystery and unexpected twists, but it works well as a straight novel. The knowing send-up of the modern-art world and the unusual and relatively cliché-free personalities of the two main characters are enough to keep you interested, even if Abel's colleague Camille is a bit too much the obvious Siobhan to his (low-alcohol) Rebus.

It's a cliché that you know you're getting old when the policemen start looking young, but it's even worse when you learn that that traumatic event in the policeman's distant past happened in the year 2000...

Claire Berest seems to be best-known for Gabriële, a book about their great-grandmother the Dadaist artist Gabriële Buffet-Picabia she co-wrote with her sister Anne Berest, but she's also written several novels independently since 2011.

Artifices (2021) by Claire Berest (France, 1982- )

(author photo French Wikipedia)

Abel Bac is a police officer with an impeccable twenty-year service record, no known vices and no private life to speak of. But he does seem to have a weak spot in the distant recesses of his adolescent memories, and there's someone out there who knows about it and is pressing on it hard, putting Abel's mental health — and his career — in peril. Not such an unusual scenario for a crime story, perhaps, except that the torture is inflicted in this case by means of highly sophisticated conceptual art installations, which all seem to be riffing in obscure fashion off a La Fontaine fable.

As a crime story it's a bit too straightforward and tightly plotted, without much room for mystery and unexpected twists, but it works well as a straight novel. The knowing send-up of the modern-art world and the unusual and relatively cliché-free personalities of the two main characters are enough to keep you interested, even if Abel's colleague Camille is a bit too much the obvious Siobhan to his (low-alcohol) Rebus.

46thorold

This is one I've been dipping into for a while, but keep forgetting to write up, mostly because it lives on the "outsize" shelf:

150 jaar Nederlandse Spoorwegaffiches (2021) by Arjan den Boer (Netherlands, 1972- )

There's a special magic in railway posters that other advertisements rarely seem to have — maybe it's because they are so often promoting travel, adventure, and far-away places (or at least cheap tickets to the seaside), or maybe it's because of the circumstances in which we look at them. But whatever the reason, railway posters do very often seem to be memorable images that call up all sorts of pleasant associations when we see them again, even if they are from 150 years ago...

Arjan den Boer takes us through the history of (graphic) advertising on Dutch railways, looking in turn at the different purposes that posters were used for, and their evolution from dense tables of information to evocative (and often quite abstract) artworks designed to be taken in at a glance. Every artist mentioned in the book also gets an entry in a separate biographical section at the end.

There isn't very much in the book about the production processes used for the posters, or about the way railway companies deployed them and evaluated their effectiveness, although we do sometimes hear about posters that were considered too controversial in one way or another.

Railways have a lot of walls to cover, and those walls are seen by a great many people in the course of a day, so when they commission artwork for their advertisements they can afford to go for the best. There are quite a few unexpected names here — the famous marine painter H W Mesdag was commissioned by the Holland Railway to create posters advertising the ferry service from Harwich to Hoek van Holland; the architect H P Berlage did another (less successful) poster for Harwich-Hoek, as well as a very architectural design advertising the North Holland Tramway Company. The artwork of illustrator Dick Bruna (famous for Nijntje/Miffy) was also very present on stations, albeit in his case advertising on behalf of the Bruna family firm, which owned an important station-bookstall concession and published a popular series of paperback books. Sadly, Piet Mondriaan never seems to have designed a railway poster, but he has certainly inspired quite a few. Most posters, of course, were and are designed by specialist commercial artists, but there also seems to have been a steady trickle of railway employees who produced artwork in their spare time.

This is a big, glossy book, published to coincide with an exhibition at the Dutch Railway Museum in Utrecht. It contains reproductions, large and small, of dozens of railway posters, many of them from Arjan den Boer's personal collection, and all very clearly and sharply reproduced.

150 jaar Nederlandse Spoorwegaffiches (2021) by Arjan den Boer (Netherlands, 1972- )

There's a special magic in railway posters that other advertisements rarely seem to have — maybe it's because they are so often promoting travel, adventure, and far-away places (or at least cheap tickets to the seaside), or maybe it's because of the circumstances in which we look at them. But whatever the reason, railway posters do very often seem to be memorable images that call up all sorts of pleasant associations when we see them again, even if they are from 150 years ago...

Arjan den Boer takes us through the history of (graphic) advertising on Dutch railways, looking in turn at the different purposes that posters were used for, and their evolution from dense tables of information to evocative (and often quite abstract) artworks designed to be taken in at a glance. Every artist mentioned in the book also gets an entry in a separate biographical section at the end.

There isn't very much in the book about the production processes used for the posters, or about the way railway companies deployed them and evaluated their effectiveness, although we do sometimes hear about posters that were considered too controversial in one way or another.

Railways have a lot of walls to cover, and those walls are seen by a great many people in the course of a day, so when they commission artwork for their advertisements they can afford to go for the best. There are quite a few unexpected names here — the famous marine painter H W Mesdag was commissioned by the Holland Railway to create posters advertising the ferry service from Harwich to Hoek van Holland; the architect H P Berlage did another (less successful) poster for Harwich-Hoek, as well as a very architectural design advertising the North Holland Tramway Company. The artwork of illustrator Dick Bruna (famous for Nijntje/Miffy) was also very present on stations, albeit in his case advertising on behalf of the Bruna family firm, which owned an important station-bookstall concession and published a popular series of paperback books. Sadly, Piet Mondriaan never seems to have designed a railway poster, but he has certainly inspired quite a few. Most posters, of course, were and are designed by specialist commercial artists, but there also seems to have been a steady trickle of railway employees who produced artwork in their spare time.

This is a big, glossy book, published to coincide with an exhibition at the Dutch Railway Museum in Utrecht. It contains reproductions, large and small, of dozens of railway posters, many of them from Arjan den Boer's personal collection, and all very clearly and sharply reproduced.

47thorold

...and, while I'm busy with picture-books, here's another one that came up via Monica's proposal that we should collectively try to read the books on RebeccaNYC 's "Hope to read soon" list (see here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/337945#). I was curious about it as a book by John Fowles I'd never come across, and I managed to find a secondhand copy.

The tree (1979) by John Fowles (UK, 1926-2005) and Frank Horvat (Italy, France, 1928-2020)

This is a collection of some sixty photographs from Frank Horvat's series "Portraits of Trees", accompanied on the facing pages by an essay by Fowles in which he reflects on the ways he and Horvat and other creative artists engage with nature in general and trees in particular, and how impoverished we are when we only see nature in a reductive, scientific, utilitarian way. It's sometimes quite difficult to focus on his quite abstract arguments when you have Horvat's gorgeous images leaping out at you from the opposite page, but it's worth it: there's more to it than holistic seventies tree-hugging.

It is quite amusing the way Fowles insists on the complexity and interelatedness of the forest whilst Horvat is doing everything he can to sterilise and isolate his specimens. You sense that his ideal tree is the one standing by itself in a snowy French field where there is no clear distinction to be seen in the background between earth and sky, whereas Fowles imagines himself in the densely wooded dells of the Undercliff at Lyme Regis. Of course, that's an oversimplification, Horvat admits a few groupings of trees and Fowles also talks about his father's immaculately pruned fruit trees, but they don't seem to have a huge amount in common.

The tree (1979) by John Fowles (UK, 1926-2005) and Frank Horvat (Italy, France, 1928-2020)

This is a collection of some sixty photographs from Frank Horvat's series "Portraits of Trees", accompanied on the facing pages by an essay by Fowles in which he reflects on the ways he and Horvat and other creative artists engage with nature in general and trees in particular, and how impoverished we are when we only see nature in a reductive, scientific, utilitarian way. It's sometimes quite difficult to focus on his quite abstract arguments when you have Horvat's gorgeous images leaping out at you from the opposite page, but it's worth it: there's more to it than holistic seventies tree-hugging.

It is quite amusing the way Fowles insists on the complexity and interelatedness of the forest whilst Horvat is doing everything he can to sterilise and isolate his specimens. You sense that his ideal tree is the one standing by itself in a snowy French field where there is no clear distinction to be seen in the background between earth and sky, whereas Fowles imagines himself in the densely wooded dells of the Undercliff at Lyme Regis. Of course, that's an oversimplification, Horvat admits a few groupings of trees and Fowles also talks about his father's immaculately pruned fruit trees, but they don't seem to have a huge amount in common.

49baswood

>47 thorold: Nice idea about an under the surface possible conflict of interest between the author and the photographer. In my view the photographer will always win because people look at the photographs first and last. I know I would.

50thorold

>47 thorold: I just noticed Horvat posted a lot of the images on his own website, if anyone wants a look. They are quite something: https://www.horvatland.com/WEB/en/THE70s/PP/PORTRAITS%20OF%20TREES/album.htm

51arubabookwoman

The tree photographs are fabulous. Seeing the photo of the book cover, I wasn't expecting so much color in many of the images (though the more muted ones are also beautiful). Each was something to savor.

52avaland

A very belated happy New Year, Mark. Lovely photo at the top. You are reading some great stuff...but then my eye caught the "Tree" book, thanks for that and the link. Will stop by from time to time.

53MissBrangwen

I enjoyed reading about the book binding. I would never have the patience required, but it was interesting to learn about the process. What a great skill to have!

54lisapeet

>47 thorold: That sounds terrific. Made me think of a favorite book from a while back, Meetings with Remarkable Trees—I think more of a coffee table type book than the one you read, but a similar way of conceptualizing trees as characters in narrative.

55thorold

Back to the Indian Ocean:

Afterlives (2020) by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Tanzania, 1948- )

This novel is set against the background of Tanzanian history from the beginning of the German colonial period until after independence, through the experiences of a family living in an unnamed coastal trading town. It looks very like a sequel to Paradise: one of the characters has a back-story that matches that book very closely, but Gurnah has changed all the names to get away from that label, and there's certainly no need to have read the earlier book.

At the centre of the book is the experience of the First World War in East Africa. This is often treated in general history books as a mere sideshow to be summed up in a rag-bag chapter on "colonial actions", but of course it was enormously disruptive for the people directly involved, the thousands of African and Asian soldiers who fought it out on behalf of the colonial powers, and the hundreds of thousands of civilians who found themselves in the path of the action and were robbed, murdered, raped, or forced to become refugees. We see this through the eyes of Hamza, who has volunteered as an Askari in the Schutztruppe to get away from his previous life, and who goes through most of the war as servant to a German officer, to emerge wounded and with a knowledge of Schiller and Heine that isn't going not help him much under British rule.

But really, something that's probably true for everything Gurnah writes, it's all about gloriously fluent, engaging storytelling, as much when he's dealing with the horrors of war as with the quiet contentments of everyday family life. He is supremely good at making you feel that you know these people and can identify with their way of seeing the world, even when it's completely different from anything you might ever have experienced yourself.

Afterlives (2020) by Abdulrazak Gurnah (Tanzania, 1948- )

This novel is set against the background of Tanzanian history from the beginning of the German colonial period until after independence, through the experiences of a family living in an unnamed coastal trading town. It looks very like a sequel to Paradise: one of the characters has a back-story that matches that book very closely, but Gurnah has changed all the names to get away from that label, and there's certainly no need to have read the earlier book.

At the centre of the book is the experience of the First World War in East Africa. This is often treated in general history books as a mere sideshow to be summed up in a rag-bag chapter on "colonial actions", but of course it was enormously disruptive for the people directly involved, the thousands of African and Asian soldiers who fought it out on behalf of the colonial powers, and the hundreds of thousands of civilians who found themselves in the path of the action and were robbed, murdered, raped, or forced to become refugees. We see this through the eyes of Hamza, who has volunteered as an Askari in the Schutztruppe to get away from his previous life, and who goes through most of the war as servant to a German officer, to emerge wounded and with a knowledge of Schiller and Heine that isn't going not help him much under British rule.

But really, something that's probably true for everything Gurnah writes, it's all about gloriously fluent, engaging storytelling, as much when he's dealing with the horrors of war as with the quiet contentments of everyday family life. He is supremely good at making you feel that you know these people and can identify with their way of seeing the world, even when it's completely different from anything you might ever have experienced yourself.

56labfs39

>55 thorold: Excellent review of Afterlives. I read Paradise a few months ago and should look for this one.

57raton-liseur

>55 thorold: I've bought and plan to read Paradise. If I like it, Afterlives might be on my list. I enjoyed reading your review, it makes me even more willing to get to this new-to-me author.

58dchaikin

>55 thorold: happy to read this. Noting!

59thorold

I've finished a book again after a long gap — caused by minor distractions and getting bogged down in several long books at once, nothing serious:

Empires of the monsoon (1996) by Richard Seymour Hall (UK, Zambia, Australia, etc., 1925-1997)

British-born journalist Dick Hall lived in Zambia during the fifties and sixties and worked for various African papers before moving back to the UK to write for the Observer. This is the last of several books he wrote on contemporary and historical African topics.

This is the classic three-decker sandwich: in the first part, we get an overview of the long-established trading patterns in the Indian Ocean driven by the predictable winds of the monsoon: the triangular traffic between Arabia, India and East Africa and the links between India and South-East Asia and China. Hall obviously loves a good story and an eye-witness, so he spends a lot of time on the stories of Captain Buzurg, Ibn Battuta, Marco Polo and various other less well-known travel-writers, as well as on the surviving accounts of China's brief flirtation with naval superpower status in the 14th century under Admiral Zheng He. But in between also manages to slip in a pretty clear account of how it all hung together, and how little medieval Europe knew of the geography and politics of the countries around the Indian Ocean.

That ignorance was in many ways at its crassest with the first incursions by European ships, the Portuguese "voyages of discovery" around the end of the fifteenth century, which are covered in the second part of the book. The treaty of Tordesillas had given the Portuguese the — supposed — right to claim most of Africa and Asia for themselves, but the people who already lived there weren't too impressed by that legal detail. Portugal didn't have the manpower and resources to establish colonial territories in the way Spain was doing in the Americas, so they relied on setting up a few small trading enclaves, in places like Goa, Sofala, and Mombasa, and on terrorising local shipping into compliance with their trading rules using their superior naval firepower. The combination of engrained Portuguese hatred for Islam with the need to make a very small number of warships impress people over a very large area resulted in some very public atrocities that often make the activities of the Spanish Conquistadors look relatively harmless in comparison. Captured seafarers and their passengers were regularly submitted to mutilation and burning alive, preferably within sight of the shore.

Needless to say, Portugal soon faced active resistance from the Ottoman Turks (helped on the quiet by their Venetian trading partners) and competition from other European ships that started to arrive in the ocean, and the Portuguese dominion over Africa and Asia never came to very much beyond Goa and a few slave plantations along the Zambezi. One odd part of the story, that Hall spends quite some time on, is King Manuel's obsession with forming an alliance with the legendarily wealthy Christian emperor Prester John, who of course never existed either in Africa or India (the legends allowed for both possibilities). The closest match that could be found was in Ethiopia, a country that was certainly Christian, but had little to offer as an ally — Portuguese efforts to establish a presence there and convert the Ethiopians to Roman Catholicism were predictably disastrous.

The final part of the book fast-forwards us through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries into the post-Napoleonic period, with a focus on Zanzibar under the crafty Sultan of Oman, Seyid Said, and his successors. The political situation has some interesting parallels to the present day: Seyid spent a lot of money with British arms manufacturers (especially in British India), so the British government, committed as it was to ending slavery, tended to overlook the fact that he controlled all the main slave-markets and most of the slave-ships in the region. And had tens of thousands of slaves working on his own plantations.

Hall also looks at how European trade goods (especially guns) and the increasing incursions of European explorers and missionaries created the volatile situation in which European colonies started to be established in East Africa, in the famous "race for Africa" of the 1870s and 80s. We get cool, hard looks at colourful figures like Burton, Speke, Livingstone and Stanley, and a few reminders of the abuses that went along with the establishment of "benign" protectorates. This process is mostly just sketched in: Hall obviously takes it for granted that readers will already know the outlines of the 20th-century history of Africa, which seems fair enough.

An interesting, lively book, with a good balance of colourful narrative and hard facts. Probably not the only book you will want to read about the region — it's pretty light on India, for example — but a good overview that also comes with with a lot of detail about East Africa that will be new to most readers.

Empires of the monsoon (1996) by Richard Seymour Hall (UK, Zambia, Australia, etc., 1925-1997)

British-born journalist Dick Hall lived in Zambia during the fifties and sixties and worked for various African papers before moving back to the UK to write for the Observer. This is the last of several books he wrote on contemporary and historical African topics.

This is the classic three-decker sandwich: in the first part, we get an overview of the long-established trading patterns in the Indian Ocean driven by the predictable winds of the monsoon: the triangular traffic between Arabia, India and East Africa and the links between India and South-East Asia and China. Hall obviously loves a good story and an eye-witness, so he spends a lot of time on the stories of Captain Buzurg, Ibn Battuta, Marco Polo and various other less well-known travel-writers, as well as on the surviving accounts of China's brief flirtation with naval superpower status in the 14th century under Admiral Zheng He. But in between also manages to slip in a pretty clear account of how it all hung together, and how little medieval Europe knew of the geography and politics of the countries around the Indian Ocean.