1baswood

Time for a new thread imaginatively labelled Baswoods books 2

Reading projects.

Elizabethan literature

Reading chronologically I am coming towards the end of 1592, which seems to be a significant year in English drama: Christopher Marlowe, Robert Greene, George Peele, John Lyly and Thomas Kyd, who had been the backbone of the London theatres all stopped writing either because of death or retirement. Leaving one William Shakespeare to keep things going until a new breed of playwrights came along. So plenty of Shakespeare to read along with some poetry from the Elizabethan sonneteers and items from the pamphlet tradition.

Unread books from my shelves

Slowly getting through some of these concentrating on authors whose surname begins with B. I have read and reviewed so far

Simone de Beauvoir - Force of Circumstances

Iain M Banks - Matter

Dorothy Baker - Cassandra at the wedding

Samuel Becket - The Becket Trilogy

Anthony Burgess - The Malayan Trilogy

William Boyd - A Good man in Africa

Julian Barnes - Flauberts Parrot

Michael Baker - Vox

Iain Banks - The Bridge

Saul Bellow - The Victim

A S Byatt - Angels and Insects

Still quite a few to read, but the numbers are not increasing because I am turning around all new books within a three week period and so they do not get put on the shelves (however the pile of books on the floor is growing)

Iain Banks - Against a dark black

Alain De Botton - The art of Travel

Anthony Burgess - The Doctor is sick

Frederick Barthelme - Moon De-luxe

William Boyd - The Blue Afternoon

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

T C Boyle - Water Music

John Baxter - A pound of Paper

John Buchan - The Island of sheep

Balzac - Old Goriot

John Berendt - Midnight in the garden of good and evil

Julian Barnes - A history of the world in 10 and a half chapters

Anthony Burgess - The Devils Mode

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are

Iain Banks - Dead Air

Saul Bellow - Herzog

Arnold Bennet - Clayhanger

Marjorie Bowen - The Bishop of hell and other stories

A S Byatt - The Childrens Book

William Boyd - Armadillo

Julian Barnes - Arthur and George

Saul Bellow - Humbolds gift

Anthony Burgess -1985

Balzac - Lost Illusions

Iain Banks - The steep approach to Goobade

William Boyd - Ordinary Thunderstorms

Anthony Burgess - The Kingdom of the wicked

Science Fiction published in 1951

I have read:

Ray Bradbury - The illustrated man

L Sprague du camp - Rogue Queen

Arthur C Clarke - Prelude to Space

Hal Clement - Ice World

Philip Jose Farmer - The lovers

Austin Hall - The Blind Spot

Robert A Heinlien - The Green Hills of Earth

Clifford Simak - Time and Again

John Wyndham - The Day of the Triffids

Robert A Heinlein The puppet Masters

Still to read:

Leigh Brackett - People of the Talisman

Fritz Leiber - Gather Darkness

Stanislaw Lem - The Astronauts

H P Lovecraft - The Hunter of the dark

Isaac Asimov The stars like dust

E C Tub - Planetfall

Jack Vance - The Dying Earth

Nelson S Bond - Lancelot Biggs Spaceman

Frederic Brown - Space on my hands

Robert Spencer Carr - Beyond Infinity

Curme Gray - Murder in Milenium VI

Raymond F Jones - The Toymaker

Arthur Koestler - The age of Longing

Henry Kuttner and C L Moore - Tomorrow and Tomorrow and the fairy chessman

William F Temple - the four sided triangle

Jack Williamson (Will Stewart) - Seetee ship

Groff Conklin - Possible world of science fiction

Kendell Foster Crossen - Adventures in tomorrow

Gill Hunt - galactic storm

Science fiction from the Masterworks series 1950's is going quite well and I think I have a chance to finish it this year.

I have read

1952 Clifford D Simak - City

1952 Bernard Wolfe - Limbo

1953 Alfred Bester - The demolished Man

1953 Ward Moore - Bring the Jubilee

1953 Theodore Sturgeon - More than Human

1953 Frederik Pohl & C M Kornbluth - The Space Merchants

1953 Arthur C Clarke - Childhoods End

1954 Richard Matheson - I Am legend

1954 Hal Clement - Mission of Gravity

1955 Jack Finney - The Body Snatchers

1955 Leigh Brackett - The Long Tomorrow

1955 The Chrysalids - John Wyndham

1956 Arthur C Clarke - The City and the Stars

1956 Double Star - Robert A Heinlein

Still to read

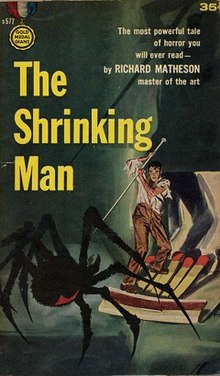

1956 Richard Matheson - The shrinking man

1956 Alfred Bester - The Stars my destiny

1957 Robert A Heinlein - The door into summer

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos - John Wyndham

1958 Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

1958 Brian W Aldiss Non-stop

1958 James Blish A case of conscience

1959 Philip K Dick - Time out of joint

1959 Kurt Vonnegut JR - The Sirens of Titan

1959 Walter M Miller - A Canticle for Leibowitz

I am also reading some proto-science fiction (before science fiction was invented) this seems to be consisting of books by Jules Verne at the moment as I have reached the 1870's

Reading projects.

Elizabethan literature

Reading chronologically I am coming towards the end of 1592, which seems to be a significant year in English drama: Christopher Marlowe, Robert Greene, George Peele, John Lyly and Thomas Kyd, who had been the backbone of the London theatres all stopped writing either because of death or retirement. Leaving one William Shakespeare to keep things going until a new breed of playwrights came along. So plenty of Shakespeare to read along with some poetry from the Elizabethan sonneteers and items from the pamphlet tradition.

Unread books from my shelves

Slowly getting through some of these concentrating on authors whose surname begins with B. I have read and reviewed so far

Simone de Beauvoir - Force of Circumstances

Iain M Banks - Matter

Dorothy Baker - Cassandra at the wedding

Samuel Becket - The Becket Trilogy

Anthony Burgess - The Malayan Trilogy

William Boyd - A Good man in Africa

Julian Barnes - Flauberts Parrot

Michael Baker - Vox

Iain Banks - The Bridge

Saul Bellow - The Victim

A S Byatt - Angels and Insects

Still quite a few to read, but the numbers are not increasing because I am turning around all new books within a three week period and so they do not get put on the shelves (however the pile of books on the floor is growing)

Iain Banks - Against a dark black

Alain De Botton - The art of Travel

Anthony Burgess - The Doctor is sick

Frederick Barthelme - Moon De-luxe

William Boyd - The Blue Afternoon

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

T C Boyle - Water Music

John Baxter - A pound of Paper

John Buchan - The Island of sheep

Balzac - Old Goriot

John Berendt - Midnight in the garden of good and evil

Julian Barnes - A history of the world in 10 and a half chapters

Anthony Burgess - The Devils Mode

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are

Iain Banks - Dead Air

Saul Bellow - Herzog

Arnold Bennet - Clayhanger

Marjorie Bowen - The Bishop of hell and other stories

A S Byatt - The Childrens Book

William Boyd - Armadillo

Julian Barnes - Arthur and George

Saul Bellow - Humbolds gift

Anthony Burgess -1985

Balzac - Lost Illusions

Iain Banks - The steep approach to Goobade

William Boyd - Ordinary Thunderstorms

Anthony Burgess - The Kingdom of the wicked

Science Fiction published in 1951

I have read:

Ray Bradbury - The illustrated man

L Sprague du camp - Rogue Queen

Arthur C Clarke - Prelude to Space

Hal Clement - Ice World

Philip Jose Farmer - The lovers

Austin Hall - The Blind Spot

Robert A Heinlien - The Green Hills of Earth

Clifford Simak - Time and Again

John Wyndham - The Day of the Triffids

Robert A Heinlein The puppet Masters

Still to read:

Leigh Brackett - People of the Talisman

Fritz Leiber - Gather Darkness

Stanislaw Lem - The Astronauts

H P Lovecraft - The Hunter of the dark

Isaac Asimov The stars like dust

E C Tub - Planetfall

Jack Vance - The Dying Earth

Nelson S Bond - Lancelot Biggs Spaceman

Frederic Brown - Space on my hands

Robert Spencer Carr - Beyond Infinity

Curme Gray - Murder in Milenium VI

Raymond F Jones - The Toymaker

Arthur Koestler - The age of Longing

Henry Kuttner and C L Moore - Tomorrow and Tomorrow and the fairy chessman

William F Temple - the four sided triangle

Jack Williamson (Will Stewart) - Seetee ship

Groff Conklin - Possible world of science fiction

Kendell Foster Crossen - Adventures in tomorrow

Gill Hunt - galactic storm

Science fiction from the Masterworks series 1950's is going quite well and I think I have a chance to finish it this year.

I have read

1952 Clifford D Simak - City

1952 Bernard Wolfe - Limbo

1953 Alfred Bester - The demolished Man

1953 Ward Moore - Bring the Jubilee

1953 Theodore Sturgeon - More than Human

1953 Frederik Pohl & C M Kornbluth - The Space Merchants

1953 Arthur C Clarke - Childhoods End

1954 Richard Matheson - I Am legend

1954 Hal Clement - Mission of Gravity

1955 Jack Finney - The Body Snatchers

1955 Leigh Brackett - The Long Tomorrow

1955 The Chrysalids - John Wyndham

1956 Arthur C Clarke - The City and the Stars

1956 Double Star - Robert A Heinlein

Still to read

1956 Richard Matheson - The shrinking man

1956 Alfred Bester - The Stars my destiny

1957 Robert A Heinlein - The door into summer

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos - John Wyndham

1958 Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

1958 Brian W Aldiss Non-stop

1958 James Blish A case of conscience

1959 Philip K Dick - Time out of joint

1959 Kurt Vonnegut JR - The Sirens of Titan

1959 Walter M Miller - A Canticle for Leibowitz

I am also reading some proto-science fiction (before science fiction was invented) this seems to be consisting of books by Jules Verne at the moment as I have reached the 1870's

2baswood

There is always time for a new project and in previous years I have discovered many new authors by picking a year at random and reading books published in that year.

As I am reading science fiction books published in 1951 it would seem churlish not to expand this to most genre books from that year. So far I have already made some discoveries having read:

John Dickson Carr - The Devil in Velvet

Camilo Jose Cela - The Hive

Julio Cortazar - Bestiario

Daphne Du Maurier - My Cousin Rachel

Francois Mauriac - Le Sagouin

There are plenty more to have a go at and so far this is the list I have compiled - fairly exhaustive I think (I have excluded children's books)

Morley Calaghan - The Loved and the lost

Rachel Carson - The Sea around us

Truman Capote - The Grass Harp

Emile Danoen - Un maison souffleé aux vents

Owen Dodson - The boy in the window

Jean Dutourd - A Dog's Head

Georges Duhamel - Cri des Profondeurs

Howard Fast - Spartacus

Jean Giorno - Le Hussard sul le toit

Julien Gracq - The Opposing shore

John Hawkes - The Beetle Leg

Shirley Jackson - Hangsaman

James Jones - From here to Eternity

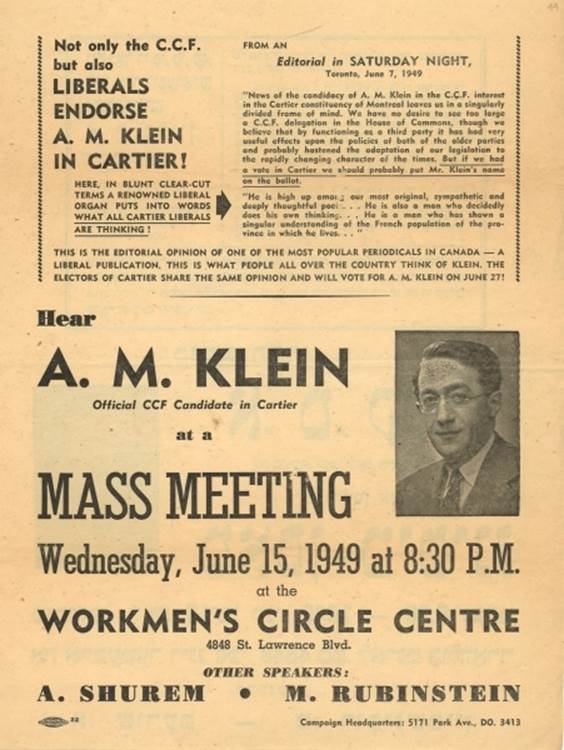

A M Klein - The second scroll

Wofgang Koeppen - Pigeons on the grass

Olivia Manning - School for love

Ngaio Marsh - Night of the Vulcan Opening night

John Masters - Nightrunners of Bengal

Nancy Mitford - The Blessing

Nicholas Monserrat - The Cruel Sea

Albert Moravia - The Conformist

Roger Nimier - Les enfants tristes

Anthony Powell - A question of upbringing

Lucien Rebatat - Les deux étendards

Sax Rohmer - Surumuru

Ernst von Salomon - The Questionaire

Ooka - Shohei - Fires on the plain

John Steinbeck - The log from the sea of Cortez

Rex Stout - Curtains for three

William Styron - Lie down in darkness

Elizabeth Taylor - A game of hide and seek

Dylan Thomas - Do not go so gentle into that good night

T H White - The Goshawk

Herman Wouk - The cain Mutiny

Marguerite Yourcenar - Memoirs of Hadrian

Eric Ambler - Judgement of Deltchev

Mulk Raj Anand - Seven summers

H E bates - Colonel Julian/selected short stories

Walter Baxter - Look Down in Mercy

Elizabeth Bowen - Early stories

John Collier - Fancies and good nights

Rhys Davies - Marianne

Alfred Duggan - Conscience of the king

James T Farrell - This man and this woman.

Nelson Algren - Chicago city on the make

W H Auden - Nones

A C Bentley - Clerihews complete

Charles Causely - Hands to dance

C Day Lewis - The poets talk

William Faulkner - Collected stories

E M Forster - Two cheers for democracy

Graham Greene - The end of the affair

Patrick Hamilton - The West Pier (Gorse Trilogy)

dasheill Hammett - Woman in the Dark

L P Hartley - The Go-between.

A P herbert - number 9

James Hilton - Morning journey

John Holloway - Language and intelligence.

Geoffrey Household - A rough shoot

sheila kaye-smith Mrs Gailey

Molly Keane - Loving without tears

Arthur koestler - The age of longing

Norman Lewis - Dragon Apparent

Sinclair Lewis - World so wide

Wyndham Lewis - Rotting Hill

Jack Lindsay - A passionate Pastoral

Eric Linklater - Laxdale Hall

Carson McCullers - The ballad of the sad Cafe

Compton Mackensie Eastern Epic

Norman Mailer - Barbary shore

Robin Maugham - The Rough and the smooth

Gladys Mitchell - Devils elbow

Wright Morris - Man and boy

Nicholas Mosely - Look at the dark

R H Mottram - One hundred and twenty eight witnesses

P H Newby - A season in England

John O'hara - The farmers hotel

V S Pritchett - Mr Beluncle

John Pudney Hero of a summer's day

Herbert Read - Byron writers and their work

J D Salinger - the catcher in the rye

William Sansom - The face of innocence

William Saroyan - Rock Wagram

C P Snow - The masters

Wallace Stevens - The Necessary Angel

William Styron - Lie down in darkness

Edith Templeton - Living on yesterday

Fred Urquhart - Jezebel's dust A

Calder Willingham - reach to the stars

Josephine Tey - The daughter of time

Agatha Christie - They came to Baghdad

Victor Serge - Memoires of a revolutionary

Ross Macdonald - The way some people die

Yukio Mishima - forbidden colors

Shohei Ooka - fires on the plain

Manuel Rojas - Hijo de Ladron - Born guilty

David Goodis - Cassidy's girl

John Gerard - autobiography of a hunted priest (Elizabethan originally in latin)

Ringstones and other curious tales - Sarban (john William Wall)

Elizabeth Yates - Amos Fortune, free man

Helen McCloy - Through a glass darkly

Cyril Hare - An English murder

Edward Atiyah - The thin line (murder my love)

Mickey Spillane - The big kill

Frederich Durrenmatt - The quarry

Robert Van Gulik - The Chinese Maze Murders

Charlotte Armstrong - Mischief

ERnst Von Salomon - The Questionnaire or answers to the 131 questions of the allied military government

Yasunari Kawabata - The Master of Go

Claud Cockburn - Beat the devil

Rex Stout - Murder by the book

Mary McMullen - Strange hold

Elswyth Thane - This was tomorrow

Thomas B Costain - The magnificent century

Robertson Davies Tempest-tost (First book of the salterton trilogy

Ann de Vries - Journey through the night

August Derleth - The memoirs of solar pons

Nevil Shute - Round the Bend

Stephen Spender - World within world

Maigret Takes a room Georges Simenon

Maigret and the burglars wife Georges Simenon

Maigret and the Gangsters Georges Simenon

The Strangers in the House Georges Simenon

Karl Kerenyl - The Gods of the Greeks

James A Michener - The Voice of Asia

Mark Van Doren - The selected letters of William Cowper

Arnold Hauser - The Social history of Art (4 volumes)

Menachem Begin - The Revolt, Begin

As I am reading science fiction books published in 1951 it would seem churlish not to expand this to most genre books from that year. So far I have already made some discoveries having read:

John Dickson Carr - The Devil in Velvet

Camilo Jose Cela - The Hive

Julio Cortazar - Bestiario

Daphne Du Maurier - My Cousin Rachel

Francois Mauriac - Le Sagouin

There are plenty more to have a go at and so far this is the list I have compiled - fairly exhaustive I think (I have excluded children's books)

Morley Calaghan - The Loved and the lost

Rachel Carson - The Sea around us

Truman Capote - The Grass Harp

Emile Danoen - Un maison souffleé aux vents

Owen Dodson - The boy in the window

Jean Dutourd - A Dog's Head

Georges Duhamel - Cri des Profondeurs

Howard Fast - Spartacus

Jean Giorno - Le Hussard sul le toit

Julien Gracq - The Opposing shore

John Hawkes - The Beetle Leg

Shirley Jackson - Hangsaman

James Jones - From here to Eternity

A M Klein - The second scroll

Wofgang Koeppen - Pigeons on the grass

Olivia Manning - School for love

Ngaio Marsh - Night of the Vulcan Opening night

John Masters - Nightrunners of Bengal

Nancy Mitford - The Blessing

Nicholas Monserrat - The Cruel Sea

Albert Moravia - The Conformist

Roger Nimier - Les enfants tristes

Anthony Powell - A question of upbringing

Lucien Rebatat - Les deux étendards

Sax Rohmer - Surumuru

Ernst von Salomon - The Questionaire

Ooka - Shohei - Fires on the plain

John Steinbeck - The log from the sea of Cortez

Rex Stout - Curtains for three

William Styron - Lie down in darkness

Elizabeth Taylor - A game of hide and seek

Dylan Thomas - Do not go so gentle into that good night

T H White - The Goshawk

Herman Wouk - The cain Mutiny

Marguerite Yourcenar - Memoirs of Hadrian

Eric Ambler - Judgement of Deltchev

Mulk Raj Anand - Seven summers

H E bates - Colonel Julian/selected short stories

Walter Baxter - Look Down in Mercy

Elizabeth Bowen - Early stories

John Collier - Fancies and good nights

Rhys Davies - Marianne

Alfred Duggan - Conscience of the king

James T Farrell - This man and this woman.

Nelson Algren - Chicago city on the make

W H Auden - Nones

A C Bentley - Clerihews complete

Charles Causely - Hands to dance

C Day Lewis - The poets talk

William Faulkner - Collected stories

E M Forster - Two cheers for democracy

Graham Greene - The end of the affair

Patrick Hamilton - The West Pier (Gorse Trilogy)

dasheill Hammett - Woman in the Dark

L P Hartley - The Go-between.

A P herbert - number 9

James Hilton - Morning journey

John Holloway - Language and intelligence.

Geoffrey Household - A rough shoot

sheila kaye-smith Mrs Gailey

Molly Keane - Loving without tears

Arthur koestler - The age of longing

Norman Lewis - Dragon Apparent

Sinclair Lewis - World so wide

Wyndham Lewis - Rotting Hill

Jack Lindsay - A passionate Pastoral

Eric Linklater - Laxdale Hall

Carson McCullers - The ballad of the sad Cafe

Compton Mackensie Eastern Epic

Norman Mailer - Barbary shore

Robin Maugham - The Rough and the smooth

Gladys Mitchell - Devils elbow

Wright Morris - Man and boy

Nicholas Mosely - Look at the dark

R H Mottram - One hundred and twenty eight witnesses

P H Newby - A season in England

John O'hara - The farmers hotel

V S Pritchett - Mr Beluncle

John Pudney Hero of a summer's day

Herbert Read - Byron writers and their work

J D Salinger - the catcher in the rye

William Sansom - The face of innocence

William Saroyan - Rock Wagram

C P Snow - The masters

Wallace Stevens - The Necessary Angel

William Styron - Lie down in darkness

Edith Templeton - Living on yesterday

Fred Urquhart - Jezebel's dust A

Calder Willingham - reach to the stars

Josephine Tey - The daughter of time

Agatha Christie - They came to Baghdad

Victor Serge - Memoires of a revolutionary

Ross Macdonald - The way some people die

Yukio Mishima - forbidden colors

Shohei Ooka - fires on the plain

Manuel Rojas - Hijo de Ladron - Born guilty

David Goodis - Cassidy's girl

John Gerard - autobiography of a hunted priest (Elizabethan originally in latin)

Ringstones and other curious tales - Sarban (john William Wall)

Elizabeth Yates - Amos Fortune, free man

Helen McCloy - Through a glass darkly

Cyril Hare - An English murder

Edward Atiyah - The thin line (murder my love)

Mickey Spillane - The big kill

Frederich Durrenmatt - The quarry

Robert Van Gulik - The Chinese Maze Murders

Charlotte Armstrong - Mischief

ERnst Von Salomon - The Questionnaire or answers to the 131 questions of the allied military government

Yasunari Kawabata - The Master of Go

Claud Cockburn - Beat the devil

Rex Stout - Murder by the book

Mary McMullen - Strange hold

Elswyth Thane - This was tomorrow

Thomas B Costain - The magnificent century

Robertson Davies Tempest-tost (First book of the salterton trilogy

Ann de Vries - Journey through the night

August Derleth - The memoirs of solar pons

Nevil Shute - Round the Bend

Stephen Spender - World within world

Maigret Takes a room Georges Simenon

Maigret and the burglars wife Georges Simenon

Maigret and the Gangsters Georges Simenon

The Strangers in the House Georges Simenon

Karl Kerenyl - The Gods of the Greeks

James A Michener - The Voice of Asia

Mark Van Doren - The selected letters of William Cowper

Arnold Hauser - The Social history of Art (4 volumes)

Menachem Begin - The Revolt, Begin

3ELiz_M

>2 baswood: You seem to have a chunk of books listed twice (School for Love caught my eye, as I title I am interested in reading and, therefore, also interested in hearing your thoughts about it, and then it caught my eye again....).

4baswood

>3 ELiz_M: Thank you, that's reduced the numbers a little.

5baswood

Philip Wylie - The Disappearance, Philip Wylie

Thus American imagination is directed—as if in the whole of life no other aims or satisfactions could be found than those of being a consumer, avid, constant and catholic.

In America, the child is schooled, if a boy, toward fiscal endeavor. It is taught to want to be a “good provider,” if not a millionaire. From babyhood it is pursued by advertisements and commercials which give it the aggregate impression that the aim of life is to acquire funds wherewith to obtain all it hears recommended. The American media of communication hypnotize it into a set of special desires. A girl, of course, takes up the same doctrine. Her aim becomes to find a mate with money to act on every radio commercial or, at the very least, to set herself up in a career which will enable her so to act, independently.

Science Fiction from 1951 and Wylie's fine but overstuffed novel flies in the face of much of what was being published at the time; It signals its intentions by having as its principal characters a philosopher (Doctor William Percival Gaunt) and his able and intelligent wife Paula. The scenario is the sudden disappearance of all the women from the world; in the blink of an eye the only human beings on the earth are male, however the women experience the same catastrophe as from their perspective all the males suddenly disappear. Alternate chapters then tell the story of a world without women and others a world without men. Both scenarios are looking towards extinction of the human race, because creating children is an impossibility.

It is 1950's America when the biggest threat to the survival of the human race was a nuclear war. The world of men soon lurch precipitously into a war with Russia. The world of women fare better, being able to negotiate and to a certain extent work together with the enemy in the hope of finding a solution to the problem of procreation. Doctor Gaunt is summoned to the White House to confer with a group of the ablest men of his generation to find a solution to the dilemma, but their convocation is soon overtaken by the need for military action. What is left of America degenerates into lawlessness and central government is again forced to take military action this time against the militias and criminal gangs that roam the country. The women in their world have different problems because there are a lack of qualified women to run the power plants, pilot the aircraft, drive the trains. There is an acute shortage of doctors, builders and engineers and so the material fabric of their world starts to break down. A major theme of the novel is not only that the two sexes need each other, but they also need each other on equal terms. The problems that the women face is because of their their lack of expertise and knowledge.

The paper that Doctor Gaunt prepares for the convocation of great minds is psychological in nature emphasising the fact that man and women of the 'West' have inhabited two utterly discrete worlds; he goes on to say that by the demeaning of women men have demeaned themselves. The answer to the problem is that men and women must come together equally to form a single unit. The Disappearance of the other sex has highlighted an opportunity that has been missed and which now psychologically has caused the permanent separation. Wylie has headed his chapter 13 as:

"AN ESSAY ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF SEX, OR THE LACK THEREOF, EXTRANEOUS TO THE NARRATIVE AND YET ITS THEME, WHICH THE IMPATIENT MAY SKIP AND THE REFLECTIVE MIGHT ENJOY."

This is the paper that Doctor Gaunt contributes to the convocation, which finds no favour with the politicians, but sets out for the readers of the book the central idea running through the novel. A little clumsy maybe but it serves to bring together the story to its conclusion. Wylie is also not frightened to raise issues around same sex love and the need for sexual fulfilment. This is a novel that castigates humanities need for always wanting more, for stripping the planet of its resources, for the dominance of one sex over the other: enlightened themes which sometimes sit uncomfortably with the story. Having created the mystery of the disappearance Wylie has the difficult task of explaining it away and readers who are looking for a satisfactory conclusion may be disappointed. I also found that some of the dialogue especially on a political level seemed a bit simplistic, but then again after listening to President Trump, Wylie might have got it just right.

This is an ambitious novel that tries to introduce philosophical/psychological ideas into a science fiction novel. It would not be a candidate for serialisation in magazines such as Weird Science or Astounding Science fiction that were popular at the time, nor would it be taken completely seriously by readers not accustomed to science fiction. However I would not condemn it as falling between two stools, but admire it for its thoughtful telling of a story that sets the imagination running and also resonates with some deeper ideas and themes. This one surprised me and so a four star read.

Let Doctor Gaunt have the last word:

Gaunt nodded. “No future in it. Strip the resources off the planet. Leave nothing for any posterity—” “That. The cockeyedness of mass production. A plenty of having things and a total dearth of living a life. You were born, educated, and then what? You tended a machine. You sat in an office. You traveled to and from it. You aged and died. Most of your active self was spent in a long, nasty, unrewarding day. Dumb or bright, poor or rich, that was the schedule for nearly all. Crazy!” “Yet most of the men who retired were miserable.” “And slaves love chains. There were too many people. They exploited their ability to stay alive. Took no responsibility for selecting the stock. For dying. For anything but breeding. And then what? The more there were the harder and harder they had to work!”

6baswood

Morley Callaghan - The Loved and the Lost, Morley Callaghan

Was Canada a cultural desert for 20th century writers before Leonard Cohen burst on the scene with an album of songs (The Songs of Leonard Cohen) or was it more to the point that if writers chose to stay in Canada they would never get a foot on the world stage. Morley Callaghan was part of the group of writers centred around Paris in 1929 which included Ernest Hemingway, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, F Scott Fitzgerald and James Joyce, unfortunately for him (as far as international fame is concerned) he chose to return to Canada. Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Stein, Joyce, Pound and er.... um Morley Callaghan? His novels were published by Scribners and he regularly had stories published in the New Yorker, but none of his novels were published in the United Kingdom. When I read the wikipedia article it would seem he was more famous for an alleged boxing match with Ernest Hemingway than any book he wrote. So then what of The Loved and the Lost his novel published in 1951 and now available on kindle.

Jim McAlpine is a college professor who leaves his post to seek his fortune and widen his horizons in a new city. He has the chance to get a regular column in a prestigious newspaper and also to romance the wealthy owners daughter. He is a man with liberal some might say progressive views but he must overcome the suspicions of the editor in chief to get employment. He charms both the owner Mr Carver and his daughter Catherine and is made to believe his appointment is only a matter of a delay of a week or two. Meanwhile he is introduced to Peggy Sanderson a sort of femme fatale, with whom he quickly falls in love. Peggy is trying to make ends meet in the city, but is not helped by her associations with some black musicians who play jazz in a dive in the black district across the tracks. Jim starts to follow her around and into the cafe where the musicians play. He must balance his chance of employment with his growing obsession for Peggy whose reputation is becoming increasingly disreputable with the English and French white communities.

The city is obviously Montreal although it is not named and it is winter time and a bitterly cold period. The snow fall seems to mirror Jim's struggle as he moves through the city with some difficulty. He shivers in pursuit of Peggy who leads him around her regular haunts, while he seeks shelter in bars and eating houses. At times he becomes lost not able to find places in which he feels secure and although he is a confident man, he is cast into a world where he starts to feel out of his depth. Morley Callaghan paints a vivid portrait of the city and keys into the events and lives of the people surrounding Jim. It is a psychological approach and although detached; in as much as there is no moral tone the author lays bare the thoughts and feelings of Jim, however hazy they might be. Peggy of course remains an enigma, but a back story of her childhood (which she tells to Jim) of her joyous relationship with a large black family when she was a child uncovers her motives to become accepted by the black community. It is a snapshot of the lives of the communities in the city told through the experiences of a select group of people. The author refuses to make any moral judgements and although a major theme of the book is black and white relationships and those between the rich and not so rich, Morley Callaghan refrains from making or leading to any judgements. It is up to the reader to find his own way. The book has an overtone of tragedy almost from the start, but this is not overplayed and the excellent pacing moves through the gears to its unsurprising conclusion. It is a dose of sharply observed reality with suspense and anticipation building through its wintry urban landscapes.

Morley Callaghan was a journalist and his sharp observations reflect this background, but there is no clipped journalistic style in his beautifully turned prose. His psychological interest do not at any stage hint at a crusade. He tells the story of the relationships between the communities with sympathy for the economic deprivation of the black people, but any stance on racism is not evident from this novel, however It was written in 1951 and so black people are referred to as negroes or mulattos and by more colloquial terms by some of the white characters. Morley Callaghan from the evidence of this novel is a major discovery for me and I look forward to reading more by him. Evidently he was an excellent writer of short stories. 4.5 stars.

7dchaikin

>5 baswood: love the quote you open this Wylie review up with

>6 baswood: Morley Callaghan? Interesting find, Bas.

>6 baswood: Morley Callaghan? Interesting find, Bas.

8baswood

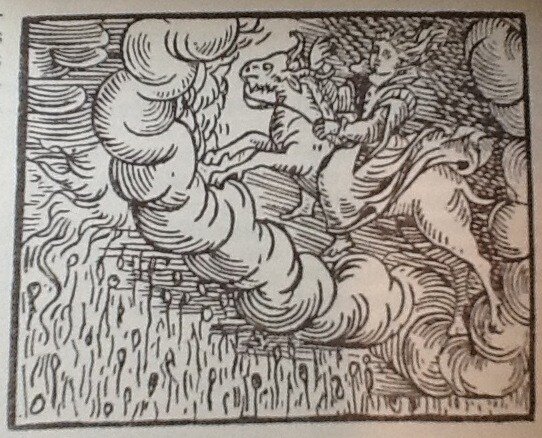

Kind-Harts Dream - Henry Chettle

Printed in 1592 the Kind-Hart; a tooth puller dreams of five apparitions that tell him of abuses by certain kinds of people. Anthony Now Now an itinerant fiddler, Dr Burcot a foreign physician, Robert Greene dramatist and poet, Tarlton the celebrated comedian and William Cuckoe an expert in coosenage, it is a series of invectives against sharp practice and confidence tricks in Elizabethan times. It is told in the style of Robert Greene in some instances and in others bears a similarity to the Martin Prelate pamphlets.

Chettle in his early career was involved in the printing industry in some capacity, which may account for this pamphlet getting into print. It does not have much to recommend it apart from bandying about the names of Elizabethan celebrities. However in his epistle to Gentlemen readers Chettle details his role in the printing of Robert Greene's Groatsworth of Wit, which had sold well. Chettle claimed that he had put the pamphlet together from Greene's papers left behind after his death. This curious explanation was probably as a result of the controversy stirred up by Groatsworth of Wit amongst writers connected with the theatre, but it has led some historians to claim that Chettle was actually the author of Groatsworth. Be that as it may Chettle's kind-Harts Dream is only for the completist.

Printed in 1592 the Kind-Hart; a tooth puller dreams of five apparitions that tell him of abuses by certain kinds of people. Anthony Now Now an itinerant fiddler, Dr Burcot a foreign physician, Robert Greene dramatist and poet, Tarlton the celebrated comedian and William Cuckoe an expert in coosenage, it is a series of invectives against sharp practice and confidence tricks in Elizabethan times. It is told in the style of Robert Greene in some instances and in others bears a similarity to the Martin Prelate pamphlets.

Chettle in his early career was involved in the printing industry in some capacity, which may account for this pamphlet getting into print. It does not have much to recommend it apart from bandying about the names of Elizabethan celebrities. However in his epistle to Gentlemen readers Chettle details his role in the printing of Robert Greene's Groatsworth of Wit, which had sold well. Chettle claimed that he had put the pamphlet together from Greene's papers left behind after his death. This curious explanation was probably as a result of the controversy stirred up by Groatsworth of Wit amongst writers connected with the theatre, but it has led some historians to claim that Chettle was actually the author of Groatsworth. Be that as it may Chettle's kind-Harts Dream is only for the completist.

9baswood

Truman Capote - The Grass harp including a tree of night and other stories.

Weird and weirder: Capote's early stories delve into small town America. The Grass Harp was published in 1951, but the other stories included in this edition are from the late 1940's. Strange characters, oddball events was it really like this? Is it still like this in America? or is this more typical of Capote, there is no hint of modernity these stories could have taken place 40 years earlier. Anachronistic perhaps because of the character profiles that Capote presents to his readers. Elderly ladies, young girls, pre teens people the stories, dysfunctional characters who rarely lift their heads from their own private worlds, but when they are forced to do so they present a challenge that must be snuffed out. The Americans in these small town stories seem to live with a certain amount of oddball behaviour: it is part of the fabric of their lives, but when weird gets weirder people get hurt.

The Grass Harp is of novella length taking up nearly half of this publication and is the best and most developed of this collection. It is narrated by Colin a young teenager small for his age a runt who when his mother dies is sent away to live with the Talbo sisters, who are well into their sixties. Verena is a business woman and runs the household; Dolly wears a veil outside the house; she ventures out once a week with her friend/servant/companion Catherine Creek a coloured woman. They collect herbs, bark and grasses to make a potion that they sell as a cure for dropsy, strictly by mail order. Dolly and Catherine live apart from Verena in their own part of the house and Colin becomes their new friend confessing that he is in love with Dolly. The event which fractures this strange household is when Verena seeing a business opportunity attempts to take over the selling of the Dropsy cure. Dolly, Catherine and Colin run away to an abandoned tree house in the woods, where they make their last stand against the forces of law and order. A young roustabout Riley Henderson and a 70 year old judge join the unlikely trio as they defend themselves against the extreme redneckery of the sheriff and his posse. There is hardly room enough in the old tree house.

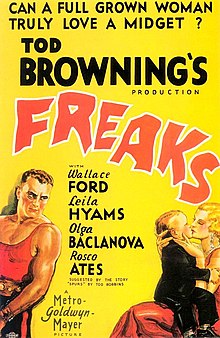

Capote treats his oddball characters with sympathy in most of his stories, they are tolerated by their community and it is only when their actions challenge others that they run into problems. His characters are not quite in the same realm as Todd Brownings film "Freaks" (1932) but some come pretty close for example in Tree of Night a young woman meets a couple on a train and the man appears to be suffering from some sort of somnambulism. The woman reveals they have a stage act entitled Lazarus where the man is buried alive. Miriam is another typical story a precocious young teen haunts the flat of a lonely 60 year old woman, taking over her life.

In another story Miss Bobbit is a precocious ten year old who moves into a small town and dominated the local people. What sets these stories apart from other weird tales collections that were popular in the 1950's is the quality of the writing and Capote's affinity with his characters. Although the Grass Harp stands head and shoulders above some of the other shorter stories Capote does not fail to provide an atmosphere of strangeness in nearly all of them. Some readers may be offended by Capote's references to black people, but one has to remember that these tales were set in 1950's small town America. Not an essential collection but worth it for the Grass Harp and so 3.5 stars.

10baswood

Iain M Banks - Against a Dark Background

This was the first Of Banks' science fiction novels that I have not enjoyed. Published in 1993 it was the first of his science fiction novels not to feature the Culture: an advanced utopian machine based empire that had become guardians of the universe. I think I probably missed the Culture which until Against a Dark Background had given Banks' novels added depth. The trouble with this book in my opinion is a lack of any depth. It is an adventure story that moves on from one incredible escapade to another. An old team of adventurers get back together in a quest to find a weapon of mass destruction, amidst a war between various religious rival sects. Death and destruction is the order of the day along with some nasty villains who specialise in torture. The heroic team are only slightly less villainous than the bad guys and the body count starts to stack up.

Banks fills out the background of his leading character: the Lady Sharrow and her family with a series of flashbacks, but in my opinion they did not add anything much to the novel. A dysfunctional family that were so dysfunctional that the destruction of their siblings seemed to be the prime mover for most of their actions. The action sequences are noisy and brutal with too much happening too quickly, the reader hardly has time to get his breath back before the novel lurches on to another confrontation. There is plenty of evidence here that Banks could write a more satisfying book: he creates some imaginative fictional worlds, full of atmosphere in which his characters must adapt to and overcome challenges and problems, for example the end of the world feel of the Sea House or Miykenns with its vegetation consisting of one single large plant, but these just seem exotic backdrops to a treasure hunting storyline that could have taken place anywhere. I found the plotting cliched and predictable. Some fine descriptive writing tends to be spoilt with some flabby dialogue by characters that could be interchangeable.

Readers of science fiction will feel that they have read plenty of stories just like this one, although the writing is of a better quality than much in this genre. This has the feel of a reworked unpublished manuscript which is exactly what it is. Three stars from me and a definite blip in my enjoyment of Banks' science fiction.

11thorold

>2 baswood: Out of curiosity, I checked my list for 1951 books, and came up with quite a few you have in your list already, plus Nevil Shute's Round the bend, which might interest you if you don't know it already. Also Stephen Spender's memoir World within world, which is something of a classic, but I don't know if you want to expand your reach to non-fiction...

You've still got Elizabeth Taylor's A game of hide and seek in your list twice. Worth reading twice, though! :-)

Wasn't Le hussard sur le toit one of the 1951 books you read earlier?

You've still got Elizabeth Taylor's A game of hide and seek in your list twice. Worth reading twice, though! :-)

Wasn't Le hussard sur le toit one of the 1951 books you read earlier?

12baswood

>11 thorold: Thanks for the heads up on World within World I have recently read a review in the LRB by Seamus Perry on Poems Written Abroad: The Lilly Library Manuscript By Stephen Spender and so an autobiography of his early years certainly merits inclusion on my list.

I will also add the Nevil Shute novel which led me to think about other prolific authors of the late 1940's early 1950s and Georges Simenon immediately sprang to mind and so four more books to add:

Maigret Takes a room

Maigret and the burglars wife

Maigret and the Gangsters

The Strangers in the House

I have deleted the double entry for Elizabeth Taylor

I have started Le Hussard sur le toit which is my current french reading - I am even slower reading in French than reading in English and so don't expect to finish it very soon.

I will also add the Nevil Shute novel which led me to think about other prolific authors of the late 1940's early 1950s and Georges Simenon immediately sprang to mind and so four more books to add:

Maigret Takes a room

Maigret and the burglars wife

Maigret and the Gangsters

The Strangers in the House

I have deleted the double entry for Elizabeth Taylor

I have started Le Hussard sur le toit which is my current french reading - I am even slower reading in French than reading in English and so don't expect to finish it very soon.

13baswood

Christopher Marlowe - Edward the Second

Ever the subversive; when Christopher Marlowe decided to write a history play he had at his disposal probably all of Raphael Holinshed's chronicles from which to chose and he chose the reign of Edward the Second. Edward was no hero king but a weak minded individual who was accused of letting his country go to rack and ruin while he indulged his favourites at court in a milieu of homoerotic dalliances. Marlowe not only succeeded in telling the story of Edwards reign but also created a tragedy with psychological dramatic overtones. Despite telescoping the action of a twenty year reign into a matter of months Marlowe created a play that works on paper and works on the stage: the number of modern revivals plays witness to its playability.

Edward II's reign has been labelled as just one squabble after another as the nobles of England sought to gain power at the expense of a king who had no stomach for war. During his reign the Scots defeated the English army at Bannockburn and the French King had seized part of Normandy. Edward surrounded himself with favourites at court particularly the Frenchman Gaveston. The Earls of Warwick, Lancaster, and the Earl of March: Mortimer plot to kill Gaveston. Edward is mortified and with the support of The Spencers (his new favourites) he declares war on the nobles. At first he is successful, but Mortimer who flees to France returns with Isabel Edwards Queen to defeat the King and his followers. Mortimer arranges for the captive king to be murdered, while making himself protector of the new KIng the young Edward III. The play ends with Edward III asserting his authority and executing Mortimer and putting his mother Isabel in the Tower of London.

Marlowe's characters develop over the course of the play; Mortimer appears first as an indignant patriot but develop into a scheming machiavellian lusting for power. Queen Isabella changes from being a patient suffering wife to a conspiring adulteress. Spencer and his attendant Baldock appear as parasitic sycophants but become loyal supporters of the king and suffer courageous deaths. Edward from a weak indulgent king to a heroic king triumphant in battle and finally to a broken and weary ruler who elicits our pity as we witness the last trace of regal dignity struggling vainly against dispare. It is king Edward who dominates the play and modern productions tend to emphasise the homosexual relationship with Gaveston that leads to the nobles incipient rage against the court favourite. Certainly the kings love for Gaveston influences and controls all his actions and homoerotic references in Marlowe's text are evident, however the overriding struggle is one of class. Gaveston and Spenser after him were not nobles by birth and the continual references to their birth right outdoes any accusations against homosexuality. The nobles force the king to send Gaveston into exile again and Edward is distraught which causes Lancaster to remark:

What passions call you these?

Afterwards Mortimer sets out his complaints against Gaveston

Uncle, his wanton humour grieves not me;

But this I scorn, that one so basely-born

Should by his sovereign's favour grow so pert,

And riot it with the treasure of the realm,

While soldiers mutiny for want of pay.

He wears a lord's revenue on his back,

And, Midas-like, he jets it in the court,

With base outlandish cullions at his heels,.......

While others walk below, the king and he,

From out a window, laugh at such as we,

And flout our train, and jest at our attire.

Uncle, 'tis this that makes me impatient.

Some critics read between the lines and claim that Mortimer's jealousy is sexual jealousy or abhorrence of homosexuality, but I don't read it this way. There is no doubt that Gaveston and the king were in some sort of love relationship, but this was hardly an issue at the time unless it was so overt it caused offence. Marlowe himself fell foul of being accused of sodomy, but was not in real danger of being sent to prison although at the time it was an offence.

The real interest for me and what makes this a great Elizabethan play is the final third starting from when Edward has lost his war with Mortimer and Queen Isabel and has sought sanctuary in an abbey. He is there with his followers Spencer and Baldock and one feels drawn to a magnetic personality, Edward was not a warrior king, but attracts people to him and his long sojourn of imprisonment and torture elicits sympathy from the reader. A tortured Edward proves difficult to kill and Mortimer must carefully select a villain to carry out the murder, one who will not feel pity for the dignified king. Marlowe tells us of the method of the murder and why it is done this way: A red hot iron spit is inserted into his anus to avoid any detection of the murder. Marlowe spares us the gory details, but lets one of the murderers say:

I fear me that this cry will raise the town.

Marlowe gives Edward some excellent speeches especially towards the end when he gives the impression of a king at a loss to understand why he is being ill treated and why he must give up his kingship, but there are moments of clear prescience when he says:

But what are kings, when regiment is gone,

But perfect shadows in a sunshine day?

The king never completely loses his dignity under duress, but one could say that earlier in the play he does lose his dignity in his declarations of love for Gaveston.

Marlowe's text is mainly in iambic pentameters with some rhyming couplets and passages of prose as is appropriate to the speaker. It flows well, but becomes a little pedestrian in the battle scenes. Marlowe introduces scenes of anti-catholicism and critiques of the kings courtiers in lively exchanges between his characters. This is one of the earliest plays to make use of Holinshed's Chronicles and tells the story of a king out of step with the need to be a strong forceful monarch in a time when the nobility were warrior princes looking to get their hands on the levers of power. This was a five star read for me and I finish with Marlowe imagining what Edwards court would be like under the influence of Pier Gaveston: (sounds good to me)

I must have wanton poets, pleasant wits,

Musicians, that with touching of a string

May draw the pliant king which way I please:

Music and poetry is his delight;

Therefore I'll have Italian masks by night,

Sweet speeches, comedies, and pleasing shows;

And in the day, when he shall walk abroad,

Like sylvan nymphs my pages shall be clad;

My men, like satyrs grazing on the lawns,

Shall with their goat-feet dance the antic hay;

Sometime a lovely boy in Dian's shape,

With hair that gilds the water as it glides

Crownets of pearl about his naked arms,

And in his sportful hands an olive-tree,

To hide those parts which men delight to see,

Shall bathe him in a spring; and there, hard by,

One like Actæon, peeping through the grove,

Shall by the angry goddess be transform'd,

And running in the likeness of an hart,

By yelping hounds pull'd down, shall semm to die:

Such things as these best please his majesty.—

Here comes my lord the king, and the nobles,

From the parliament. I'll stand aside.

14thorold

>13 baswood: Yes, but what about the bit where Annie Lennox sings "Every time we say goodbye"...? :-)

I'm just reading a biography of Frederick the Great — maybe I should re-read the Marlowe (or dig out the VHS tape of Jarman's version, at least) for "compare and contrast" purposes.

ETA: ...and I'd never spotted that that was where Huxley got Antic hay from!

I'm just reading a biography of Frederick the Great — maybe I should re-read the Marlowe (or dig out the VHS tape of Jarman's version, at least) for "compare and contrast" purposes.

ETA: ...and I'd never spotted that that was where Huxley got Antic hay from!

15dchaikin

Great review, great prep should get to Marlowe

I noticed my library has 17 books tagged 1951. (Not all are novels, some are books for kids. Also several are duplicates, including Arnold Hauser’s 4 volume Social History of Art, that I put it as 4 separate entries.) direct link: https://www.librarything.com/catalog/dchaikin&tag=1951

I noticed my library has 17 books tagged 1951. (Not all are novels, some are books for kids. Also several are duplicates, including Arnold Hauser’s 4 volume Social History of Art, that I put it as 4 separate entries.) direct link: https://www.librarything.com/catalog/dchaikin&tag=1951

16baswood

Time to take stock of the reading projects - half way through the year

Elizabethan Literature

This one has gone quite well - I have now read all of the available plays by the early pre-Shakespeare dramatists: John Lyly, George Peele, Thomas Kyd, Robert Greene and Christopher Marlowe and other bits and pieces published in 1591 and find myself halfway through 1592 and so I am on course to crash through into 1593.

Unread books from my shelves (authors surnames beginning with B)

I have 38 books listed and so far I have read only 12

Still to read

Alain De Botton - The art of Travel

Anthony Burgess - The Doctor is sick

Frederick Barthelme - Moon De-luxe

William Boyd - The Blue Afternoon

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

T C Boyle - Water Music

John Baxter - A pound of Paper

John Buchan - The Island of sheep

Balzac - Old Goriot

John Berendt - Midnight in the garden of good and evil

Julian Barnes - A history of the world in 10 and a half chapters

Anthony Burgess - The Devils Mode

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are

Iain Banks - Dead Air

Saul Bellow - Herzog

Arnold Bennet - Clayhanger

Marjorie Bowen - The Bishop of hell and other stories

A S Byatt - The Childrens Book

William Boyd - Armadillo

Julian Barnes - Arthur and George

Saul Bellow - Humbolds gift

Anthony Burgess -1985

Balzac - Lost Illusions

Iain Banks - The steep approach to Goobade

William Boyd - Ordinary Thunderstorms

Anthony Burgess - The Kingdom of the wicked

Science fiction books published in 1951

29 books listed and 10 read so far

Still to read:

Leigh Brackett - People of the Talisman

Fritz Leiber - Gather Darkness

Stanislaw Lem - The Astronauts

H P Lovecraft - The Hunter of the dark

Isaac Asimov The stars like dust

E C Tub - Planetfall

Jack Vance - The Dying Earth

Nelson S Bond - Lancelot Biggs Spaceman

Frederic Brown - Space on my hands

Robert Spencer Carr - Beyond Infinity

Curme Gray - Murder in Milenium VI

Raymond F Jones - The Toymaker

Arthur Koestler - The age of Longing

Henry Kuttner and C L Moore - Tomorrow and Tomorrow and the fairy chessman

William F Temple - the four sided triangle

Jack Williamson (Will Stewart) - Seetee ship

Groff Conklin - Possible world of science fiction

Kendell Foster Crossen - Adventures in tomorrow

Gill Hunt - galactic storm

Science fiction from the masterworks series 1950's

24 listed and fifteen read - this looks promising

still to read:

1956 Richard Matheson - The shrinking man

1956 Alfred Bester - The Stars my destiny

1957 Robert A Heinlein - The door into summer

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos - John Wyndham

1958 Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

1958 Brian W Aldiss Non-stop

1958 James Blish A case of conscience

1959 Philip K Dick - Time out of joint

1959 Kurt Vonnegut JR - The Sirens of Titan

1959 Walter M Miller - A Canticle for Leibowitz

Books published in 1951 looks like it's going to be two year project 128 books and I have read 7

Elizabethan Literature

This one has gone quite well - I have now read all of the available plays by the early pre-Shakespeare dramatists: John Lyly, George Peele, Thomas Kyd, Robert Greene and Christopher Marlowe and other bits and pieces published in 1591 and find myself halfway through 1592 and so I am on course to crash through into 1593.

Unread books from my shelves (authors surnames beginning with B)

I have 38 books listed and so far I have read only 12

Still to read

Alain De Botton - The art of Travel

Anthony Burgess - The Doctor is sick

Frederick Barthelme - Moon De-luxe

William Boyd - The Blue Afternoon

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

T C Boyle - Water Music

John Baxter - A pound of Paper

John Buchan - The Island of sheep

Balzac - Old Goriot

John Berendt - Midnight in the garden of good and evil

Julian Barnes - A history of the world in 10 and a half chapters

Anthony Burgess - The Devils Mode

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are

Iain Banks - Dead Air

Saul Bellow - Herzog

Arnold Bennet - Clayhanger

Marjorie Bowen - The Bishop of hell and other stories

A S Byatt - The Childrens Book

William Boyd - Armadillo

Julian Barnes - Arthur and George

Saul Bellow - Humbolds gift

Anthony Burgess -1985

Balzac - Lost Illusions

Iain Banks - The steep approach to Goobade

William Boyd - Ordinary Thunderstorms

Anthony Burgess - The Kingdom of the wicked

Science fiction books published in 1951

29 books listed and 10 read so far

Still to read:

Leigh Brackett - People of the Talisman

Fritz Leiber - Gather Darkness

Stanislaw Lem - The Astronauts

H P Lovecraft - The Hunter of the dark

Isaac Asimov The stars like dust

E C Tub - Planetfall

Jack Vance - The Dying Earth

Nelson S Bond - Lancelot Biggs Spaceman

Frederic Brown - Space on my hands

Robert Spencer Carr - Beyond Infinity

Curme Gray - Murder in Milenium VI

Raymond F Jones - The Toymaker

Arthur Koestler - The age of Longing

Henry Kuttner and C L Moore - Tomorrow and Tomorrow and the fairy chessman

William F Temple - the four sided triangle

Jack Williamson (Will Stewart) - Seetee ship

Groff Conklin - Possible world of science fiction

Kendell Foster Crossen - Adventures in tomorrow

Gill Hunt - galactic storm

Science fiction from the masterworks series 1950's

24 listed and fifteen read - this looks promising

still to read:

1956 Richard Matheson - The shrinking man

1956 Alfred Bester - The Stars my destiny

1957 Robert A Heinlein - The door into summer

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos - John Wyndham

1958 Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

1958 Brian W Aldiss Non-stop

1958 James Blish A case of conscience

1959 Philip K Dick - Time out of joint

1959 Kurt Vonnegut JR - The Sirens of Titan

1959 Walter M Miller - A Canticle for Leibowitz

Books published in 1951 looks like it's going to be two year project 128 books and I have read 7

17baswood

>Thanks for that link Dan I have added the following to my list

Karl Kerenyl - The Gods of the Greeks

James A Michener - The Voice of Asia

Mark Van Doren - The selected letters of William Cowper

Arnold Hauser - The Social history of Art (4 volumes)

Menachem Begin - The Revolt, Begin

Karl Kerenyl - The Gods of the Greeks

James A Michener - The Voice of Asia

Mark Van Doren - The selected letters of William Cowper

Arnold Hauser - The Social history of Art (4 volumes)

Menachem Begin - The Revolt, Begin

18baswood

Time to take stock of the reading projects - half way through the year

Elizabethan Literature

This one has gone quite well - I have now read all of the available plays by the early pre-Shakespeare dramatists: John Lyly, George Peele, Thomas Kyd, Robert Greene and Christopher Marlowe and other bits and pieces published in 1591 and find myself halfway through 1592 and so I am on course to crash through into 1593.

Unread books from my shelves (authors surnames beginning with B)

I have 38 books listed and so far I have read only 12

Still to read

Alain De Botton - The art of Travel

Anthony Burgess - The Doctor is sick

Frederick Barthelme - Moon De-luxe

William Boyd - The Blue Afternoon

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

T C Boyle - Water Music

John Baxter - A pound of Paper

John Buchan - The Island of sheep

Balzac - Old Goriot

John Berendt - Midnight in the garden of good and evil

Julian Barnes - A history of the world in 10 and a half chapters

Anthony Burgess - The Devils Mode

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are

Iain Banks - Dead Air

Saul Bellow - Herzog

Arnold Bennet - Clayhanger

Marjorie Bowen - The Bishop of hell and other stories

A S Byatt - The Childrens Book

William Boyd - Armadillo

Julian Barnes - Arthur and George

Saul Bellow - Humbolds gift

Anthony Burgess -1985

Balzac - Lost Illusions

Iain Banks - The steep approach to Goobade

William Boyd - Ordinary Thunderstorms

Anthony Burgess - The Kingdom of the wicked

Science fiction books published in 1951

29 books listed and 10 read so far

Still to read:

Leigh Brackett - People of the Talisman

Fritz Leiber - Gather Darkness

Stanislaw Lem - The Astronauts

H P Lovecraft - The Hunter of the dark

Isaac Asimov The stars like dust

E C Tub - Planetfall

Jack Vance - The Dying Earth

Nelson S Bond - Lancelot Biggs Spaceman

Frederic Brown - Space on my hands

Robert Spencer Carr - Beyond Infinity

Curme Gray - Murder in Milenium VI

Raymond F Jones - The Toymaker

Arthur Koestler - The age of Longing

Henry Kuttner and C L Moore - Tomorrow and Tomorrow and the fairy chessman

William F Temple - the four sided triangle

Jack Williamson (Will Stewart) - Seetee ship

Groff Conklin - Possible world of science fiction

Kendell Foster Crossen - Adventures in tomorrow

Gill Hunt - galactic storm

Science fiction from the masterworks series 1950's

24 listed and fifteen read - this looks promising

still to read:

1956 Richard Matheson - The shrinking man

1956 Alfred Bester - The Stars my destiny

1957 Robert A Heinlein - The door into summer

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos - John Wyndham

1958 Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

1958 Brian W Aldiss Non-stop

1958 James Blish A case of conscience

1959 Philip K Dick - Time out of joint

1959 Kurt Vonnegut JR - The Sirens of Titan

1959 Walter M Miller - A Canticle for Leibowitz

Books published in 1951 looks like it's going to be a 2/3 year project - 128 books (now 136 after >15 dchaikin:)

I have read 7 so far.

Elizabethan Literature

This one has gone quite well - I have now read all of the available plays by the early pre-Shakespeare dramatists: John Lyly, George Peele, Thomas Kyd, Robert Greene and Christopher Marlowe and other bits and pieces published in 1591 and find myself halfway through 1592 and so I am on course to crash through into 1593.

Unread books from my shelves (authors surnames beginning with B)

I have 38 books listed and so far I have read only 12

Still to read

Alain De Botton - The art of Travel

Anthony Burgess - The Doctor is sick

Frederick Barthelme - Moon De-luxe

William Boyd - The Blue Afternoon

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

T C Boyle - Water Music

John Baxter - A pound of Paper

John Buchan - The Island of sheep

Balzac - Old Goriot

John Berendt - Midnight in the garden of good and evil

Julian Barnes - A history of the world in 10 and a half chapters

Anthony Burgess - The Devils Mode

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are

Iain Banks - Dead Air

Saul Bellow - Herzog

Arnold Bennet - Clayhanger

Marjorie Bowen - The Bishop of hell and other stories

A S Byatt - The Childrens Book

William Boyd - Armadillo

Julian Barnes - Arthur and George

Saul Bellow - Humbolds gift

Anthony Burgess -1985

Balzac - Lost Illusions

Iain Banks - The steep approach to Goobade

William Boyd - Ordinary Thunderstorms

Anthony Burgess - The Kingdom of the wicked

Science fiction books published in 1951

29 books listed and 10 read so far

Still to read:

Leigh Brackett - People of the Talisman

Fritz Leiber - Gather Darkness

Stanislaw Lem - The Astronauts

H P Lovecraft - The Hunter of the dark

Isaac Asimov The stars like dust

E C Tub - Planetfall

Jack Vance - The Dying Earth

Nelson S Bond - Lancelot Biggs Spaceman

Frederic Brown - Space on my hands

Robert Spencer Carr - Beyond Infinity

Curme Gray - Murder in Milenium VI

Raymond F Jones - The Toymaker

Arthur Koestler - The age of Longing

Henry Kuttner and C L Moore - Tomorrow and Tomorrow and the fairy chessman

William F Temple - the four sided triangle

Jack Williamson (Will Stewart) - Seetee ship

Groff Conklin - Possible world of science fiction

Kendell Foster Crossen - Adventures in tomorrow

Gill Hunt - galactic storm

Science fiction from the masterworks series 1950's

24 listed and fifteen read - this looks promising

still to read:

1956 Richard Matheson - The shrinking man

1956 Alfred Bester - The Stars my destiny

1957 Robert A Heinlein - The door into summer

1957 The Midwich Cuckoos - John Wyndham

1958 Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

1958 Brian W Aldiss Non-stop

1958 James Blish A case of conscience

1959 Philip K Dick - Time out of joint

1959 Kurt Vonnegut JR - The Sirens of Titan

1959 Walter M Miller - A Canticle for Leibowitz

Books published in 1951 looks like it's going to be a 2/3 year project - 128 books (now 136 after >15 dchaikin:)

I have read 7 so far.

19dchaikin

“I have now read all of the available plays by the early pre-Shakespeare dramatists”

That’s pretty amazing, Bass. Looking forward to your 1593.

That’s pretty amazing, Bass. Looking forward to your 1593.

20baswood

John Hawkes -The Beetle Leg

When I pick up a book by an author new to me who has gained some critical appreciation over the years, I look for clues as to style and content. I will usually read the first fifty or so pages and hope by that time I will have a handle on the writing that will enhance my enjoyment of the book. The Beetle Leg has a front cover that could be described as contemporary featuring a black on white jagged design which is anything but comfortable. The inside page tells me that it is "a new directions book" I was not surprised therefore to find a piece of experimental writing with sentences of unusual constructions, not that they were ungrammatical, but they turned this way and that with nouns adjectives and verbs that made them seem as jagged as the design on that front cover. I was not surprised that there was no narrative shape to speak of or that the book failed to follow a linear progression. I got used to the fact that events jumped around in time, but was thankful that the characters seemed to appear regularly enough to give some sense of consistency. However fifty pages in and I needed more information on the author and his style.

The most quotable reference from the author himself was:

''I began to write fiction on the assumption that the true enemies of the novel were plot, character, setting and theme, and having once abandoned these familiar ways of thinking about fiction, totality of fiction or structure was really all that remained. And structure -- verbal and psychological coherence -- is still my largest concern as a writer.''

and then that the New York Times had said Mr Hawkes:

was called a figure ''in a post-modern pantheon of experimental novelists who include John Barth, William Gass and William Gaddis'' by Mel Gussow in The New York Times in 1996.

Mr. Gaddis once said Mr. Hawkes's ''sentences are themselves 'events.' ‘'

Armed with this information I could read on in confidence knowing I was just going along for the sheer hell of the ride. I didn't need to worry about plot, characterisation or narrative drive, but I did have to pay attention to what those sentences were telling me or it would all pass me by in something like a blur so that I would be hard pressed to come to any conclusion about what I had just read.

The Beetle leg was published in 1951 and was the second of Hawkes fourteen published books. I had bought an electronic copy, because any surviving printed copies are quite expensive, which may tell its own story. It has a setting and there are recurring themes that can be picked out. The setting is Minnesota (America) Clare county in a small town that sat beside a dam and at some point in the narrative the dam burst (the great slide)flooding some or all of a town which now lies beneath a lake. There was one fatality Mulge Lampson brother of Luke Lampson and his family and friends have him on their mind as they go about their lives.

It is a harsh landscape that is stifling hot in the summer and very cold in the winter, it is a landscape for hardy people and native Americans and Hawkes sketches in the feel of the first arrivals to the area coping with the harsh conditions in a sort of tent city. It has the feel of a western which is enhanced by the current sheriff of the town and his dealing with a motorcycle gang known as the red Devils. We meet the sheriff in the first pages of the novel who reflects "It is a lawless country" a bit like the novel itself.

There is a primitive feel to the whole thing. Ma (Lukes Ma) prepares herself and her wagon for a wedding: she might be re-enacting a marriage to Mulge, but at her age she must face down the other women. Camper comes back to the town after an absence and wants to fish in the lake, Cap. Leech runs a medical business from the back of his wagon which is primitive in the extreme. Both of these characters stir up old hostilities. It is a mean hard world where people just get on with their lives.

The novel has its share of shocking images:

He lifted the huckleberry pole and there, biting the hook, swung the heavy body of a baby that had been dropped, searched for, and lost in the flood. The eyes slept on either side of the fish line and a point of the barb protruded near the nose stopped with silt. It turned slowly around and around on the end of the wet string that cut in half its forehead. It had been tumbled under exposed roots and with creatures too dumb to swim, long days through the swell, neither sunk nor floating. The white stomach hung full with all it had swallowed. God’s naked child lay under Luke’s fingers on the spread poncho, as on his knees and up to his thighs in the river, he loosed the hook, forcing his hand to touch the half-made face. His hook cracked through the membrane of the palate; he touched cold scales on the neck. One of the newborn sucked inside a gentle wave to the bottom of a stunted water black tree, its body rolled on the slippery poncho while the crouching figure of a young man shut his eyes, wet his lips. In both hands he picked it up, circling the softened chest inside of which lay the formless lungs, and stooped again to the water. As his feet moved it thickly eddied, splashed. He held the body closer to the surface, water touched the back of his knuckles, and letting go, he gently pushed it off as if it would turn over and quickly swim away to the center of the bankless stream.

I was not expecting any resolution and I was not disappointed, but we do get a reflection by Cap Leech when he finds the body of the drowned Lampson brother. I was intrigued by the reading experience and once used to the style of the writing there was enough to cling onto and to enjoy the vignettes without worrying too much about where it was all leading. To be fair we know this almost from the start when the Sheriff talks about the one fatality and the great slide. 3.5 stars.

21baswood

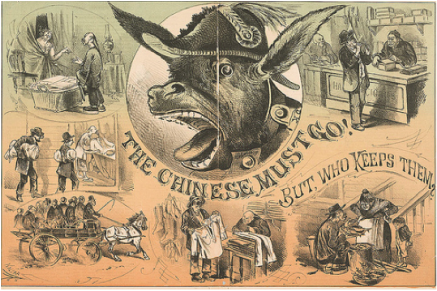

The Last Days of the Republic, P W Dooner - P W Dooner

This book has been listed in a genre of anti-enlightenment invasion fiction. Published in 1880 it foretold the invasion of America by China from the vantage point of a historian looking back from the early years of the 20th century. Neither Pierton W Dooner or his book has a page on wikipedia, but he can be tracked down in 1870 when he was the editor of a weekly newspaper: the Arizonian based is Tuscon. Described as a pioneer editor Dooner certainly had run-ins with local politicians which resulted in him having to close down his paper and leave the territory. He moved on to California where he later practiced law. His altercations with politicians may have been responsible for his views of the state of America in 1880 which take up the first four chapters of his book. According to him it is a country riven with political controversy and greed and therefore ripe for invasion.

It was probably the fears of Asian invasions sparked off by the employment of Chinese labour on the Central Pacific Railroad in the 1860's leading to the Californian State Legislature passing an Anti-Coolie Act that gave Dooner the idea for his book. He describes California as a state where the rich were getting richer by hiring Chinese labourers and undercutting the American workers. This resulted in racial tensions and politicians needed to agree on how to deal with the issues, but owing to individual self interest no consensus could be achieved. It has to be said that Dooner is deeply prejudiced against the Chinese workers and saw them as an advanced force for an invasion by the mother country:

‘This unwholesome spirit (a servile attitude), seconded by a consuming avarice and directed by a most incredible cunning; laid the foundations of a scheme of conquest, unparalleled in the human race.'

The Chinese took the place of the negro workers in the Southern States, because they would work hard in worse conditions, however they were organised amongst themselves and the advanced guard of Chinese coolies became militarised as more and more of them flooded into America. They formed their own army and quick local victories were supported by mainland China. They were more ruthless than their American counterparts and better organised and although the American fought bravely they were overcome in a matter of a few years, mainly because of the numbers of Chinese on the battlefield and their ability to put up with atrocious conditions and needing only a bowl full of rice for sustenance. The American resistance was fractured by disagreements and the old divisions between the North and the South reappeared.

This is a political diatribe rather than a novel. A diatribe that would play on the fears of its english readership. Populist fiction dressed up to look like a well thought out road map of the future. Reprehensible of course, but it has ben considered as an example of invasion literature. It all sounds half-baked today and I hope it did when it was published. 2 stars.

22rocketjk

>20 baswood: In grad school I took a seminar during which we spent the semester reading John Barth and John Hawkes. We didn't read The Beetle Leg, though. According to the professor, who was a huge Hawkes devotee, Hawkes was influenced by Graham Greene, and The Lime Twig was inspired by Brighton Rock. The professor was a bit of a character and more than a little opinionated (I got called "erudite" in class once for speaking up to agree with him about something) but passionate and I would think only someone with those qualifications could teach an effective class about these two authors.

>21 baswood: Interesting.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in California actually wasn't repealed until 1943, as China had become America's ally in World War Two.

Anyway, fascinating reading and great reviews as always.

>21 baswood: Interesting.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in California actually wasn't repealed until 1943, as China had become America's ally in World War Two.

Anyway, fascinating reading and great reviews as always.

23dchaikin

(The hell with Dooner.) I enjoyed your take on Hawkes, who I’m unfamiliar with. I partially agree with his comment about the novel. I could maybe see “plot, character, setting and theme” as an enemy to a novelist, but I’m not sure they need be abandoning altogether. Obviously he has a little of them all within this book.

24baswood

>22 rocketjk: Interesting about your semester reading John Barth and John Hawkes. It would seem that Hawkes has faded from view a little over the years. I would be happy to attempt something else by him. Hawkes himself took creative writing classes.

>23 dchaikin: I agree Dan (The hell with Dooner)

>23 dchaikin: I agree Dan (The hell with Dooner)

25baswood

Samuel Daniel - Delia, the Complaint of Rosamond.

The critical view of the Delia sonnet sequence is that it is beautiful but mediocre, well written but limited in scope. A masterpiece of phrasing and melody, but which offers no ideas, no psychology and no story. Perhaps it could be summed up as a sequence that will appeal to poets and lovers of form, but may leave the general reader a little cold. This would be a pity because two themes emerge which are treated at length: a sustained elegiac lament on the passing of youth (and beauty) and a declaration of faith in the survival of the poets vision. These are not new themes for the Elizabethan sonneteers and some may feel they are too dominant in a sequence that is meant to be about love, although to be fair courtly love.