thorold thrusts out knees and feet in Q4 2018

CharlasClub Read 2018

Únete a LibraryThing para publicar.

Este tema está marcado actualmente como "inactivo"—el último mensaje es de hace más de 90 días. Puedes reactivarlo escribiendo una respuesta.

1thorold

Oh, good gigantic smile o’ the brown old earth,

This autumn morning! How he sets his bones

To bask i’ the sun, and thrusts out knees and feet

For the ripple to run over in its mirth;

Listening the while, where on the heap of stones

The white breast of the sea-lark twitters sweet.

That is the doctrine, simple, ancient, true;

Such is life’s trial, as old earth smiles and knows.

If you loved only what were worth your love,

Love were clear gain, and wholly well for you:

Make the low nature better by your throes!

Give earth yourself, go up for gain above!

Robert Browning - "Among the Rocks" - from Dramatis personae, 1864

Amsterdamse Waterleidingduinen, November 2017

2thorold

This is the follow-on from my Q3 thread, which was here: http://www.librarything.com/topic/293138

Unrealistic reading goals for Q4 - lazily updated from Q3:

- European history (only about900 300 pages to go in Jonathan Israel, and I want to find out who did it...); after that I've got Geoffrey Parker's Imprudent King and Tim Blanning's Frederick the Great lined up

-Central Asia Transitions for Reading Globally

- Travel writing/Great Outdoors - follow-up from Q2/Q3 and my own outdoor activities

- More Spanish

- Belle van Zuylen/Mme de Charrière - I was reminded about her by visiting Zuylen Castle a couple ofweeks months ago

- More 19th century - Zola, Trollope, Balzac, Hardy ...

- Maybe something Italian, as I've got another trip lined up...?

- The TBR pile (this time it's really going to be tackled ... No, wait, who am I kidding?)

Unrealistic reading goals for Q4 - lazily updated from Q3:

- European history (only about

-

- Travel writing/Great Outdoors - follow-up from Q2/Q3 and my own outdoor activities

- More Spanish

- Belle van Zuylen/Mme de Charrière - I was reminded about her by visiting Zuylen Castle a couple of

- More 19th century - Zola, Trollope, Balzac, Hardy ...

- Maybe something Italian, as I've got another trip lined up...?

- The TBR pile (this time it's really going to be tackled ... No, wait, who am I kidding?)

3thorold

Quick summary of Q3:

32 books read in Q3 (Q1: 51, Q2: 44):

Author gender: F 16; M 16

By main category: Crime 13; Fiction 12; Poetry 2; Travel 4; History 1

By language: French 7; English 20; Dutch 3; German 1; Spanish 1

(Of the 20 English books, 12 were translations - original language Swedish 10; Japanese 1; Turkish 1)

By original publication date: Earliest 1843; latest 2017; mean 1979, median 2000. 3 books were published in the last five years; 3 were published before 1900.

By format: 10 physical books from the TBR; 18 read-but-not-owned (free e-books or public library); 4 paid e-books

20 distinct authors read in Q3 (Q1: 41, Q2: 32):

Author gender: F 6; M 14

By country: UK 5; FR 4; NL 2; CA 1; AU 1; ES 1; TK 1; CH 1; IE 1; SE 1; MA 1; JP 1

- Hmm, I think I can see a trend in the number of books - three points counts as a straight line for an ex-physicist! Good weather and travel may have accounted for much of the decline, but it's also clearly got something to do with the presence of quite a few thick books, including two Zolas and a Balzac.

- And Jonathan Israel's The Dutch Republic, started in Q2, in which I advanced about 600 pages in Q3. Not a book that can be rushed, and at nearly 1.7kg it's not one that can be read on the train or in bed, either...

- On the other hand, I did read all ten of Helene Tursten's Swedish crime novels, at the rate of about one a day

Highlights of Q3:

- Illusions perdues by Honoré de Balzac - almost the perfect 19th century European novel

- The Makioka sisters by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki - a wonderful 20th century Japanese riff on the 19th century European novel

- The invention of tradition edited by Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger - why we shouldn't trust what we think we know about the past

- and the obligatory surprise entrant: Une enquête au pays by Driss Chraïbi

32 books read in Q3 (Q1: 51, Q2: 44):

Author gender: F 16; M 16

By main category: Crime 13; Fiction 12; Poetry 2; Travel 4; History 1

By language: French 7; English 20; Dutch 3; German 1; Spanish 1

(Of the 20 English books, 12 were translations - original language Swedish 10; Japanese 1; Turkish 1)

By original publication date: Earliest 1843; latest 2017; mean 1979, median 2000. 3 books were published in the last five years; 3 were published before 1900.

By format: 10 physical books from the TBR; 18 read-but-not-owned (free e-books or public library); 4 paid e-books

20 distinct authors read in Q3 (Q1: 41, Q2: 32):

Author gender: F 6; M 14

By country: UK 5; FR 4; NL 2; CA 1; AU 1; ES 1; TK 1; CH 1; IE 1; SE 1; MA 1; JP 1

- Hmm, I think I can see a trend in the number of books - three points counts as a straight line for an ex-physicist! Good weather and travel may have accounted for much of the decline, but it's also clearly got something to do with the presence of quite a few thick books, including two Zolas and a Balzac.

- And Jonathan Israel's The Dutch Republic, started in Q2, in which I advanced about 600 pages in Q3. Not a book that can be rushed, and at nearly 1.7kg it's not one that can be read on the train or in bed, either...

- On the other hand, I did read all ten of Helene Tursten's Swedish crime novels, at the rate of about one a day

Highlights of Q3:

- Illusions perdues by Honoré de Balzac - almost the perfect 19th century European novel

- The Makioka sisters by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki - a wonderful 20th century Japanese riff on the 19th century European novel

- The invention of tradition edited by Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger - why we shouldn't trust what we think we know about the past

- and the obligatory surprise entrant: Une enquête au pays by Driss Chraïbi

4thorold

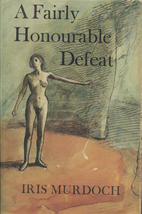

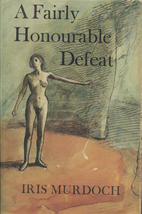

...and on to the first book I finished in Q4. It's rather wonderful how I still keep stumbling across Iris Murdoch novels I didn't know I still had to read. And even better that I found this one in a hardcover with John Sergeant art on the dust jacket, with a yellowing newspaper cutting of the review by H van der Kroft in the NRC still tucked into it (they liked it, with some reservations about the opening chapter):

A fairly honourable defeat (1970) by Iris Murdoch (UK, 1919-1999)

A staple of many classic comedy plots is the malevolent genius who - usually to prove a point or settle a bet - does the author's work by manipulating other characters into betraying their partners. Eventually it's all resolved and we leave everyone at the end of Act III confused and a little bit disillusioned but otherwise unharmed. Shakespeare uses it all the time, and possibly the most perfect example is in Mozart's Così fan tutte. And we all know it's a stage convention and enjoy it, even if Mozart reminds us that this is dangerous stuff to play with. But what if it wasn't a comedy, and someone started doing that sort of thing to real people like you and me? - Or at least people like the sort Iris Murdoch knew in 1970, the senior civil servants, academics, students and middle-class housewives of contemporary London.

Murdoch explores the nasty things that can happen when you deliberately take people's illusions away from them and play around cynically with their emotions. The mix of psychological realism and farce is full of strange twisted variants on comedy set-pieces, like the stolen letters, the eavesdropping scene, the nude scene, the burnt-dinner scene, and even the falling-in-the-pool scene, and it can't help being funny, but it's funny in a very grim sort of way, and you know this isn't going to end well. It sometimes seems to be taking Adorno's famous dictum a step further and showing where social comedy fails us in a mid-20th century world that has to deal with the Holocaust and the threat of global nuclear destruction. Or maybe it's saying that only (black) comedy can deal with such a world...?

A fairly honourable defeat (1970) by Iris Murdoch (UK, 1919-1999)

A staple of many classic comedy plots is the malevolent genius who - usually to prove a point or settle a bet - does the author's work by manipulating other characters into betraying their partners. Eventually it's all resolved and we leave everyone at the end of Act III confused and a little bit disillusioned but otherwise unharmed. Shakespeare uses it all the time, and possibly the most perfect example is in Mozart's Così fan tutte. And we all know it's a stage convention and enjoy it, even if Mozart reminds us that this is dangerous stuff to play with. But what if it wasn't a comedy, and someone started doing that sort of thing to real people like you and me? - Or at least people like the sort Iris Murdoch knew in 1970, the senior civil servants, academics, students and middle-class housewives of contemporary London.

Murdoch explores the nasty things that can happen when you deliberately take people's illusions away from them and play around cynically with their emotions. The mix of psychological realism and farce is full of strange twisted variants on comedy set-pieces, like the stolen letters, the eavesdropping scene, the nude scene, the burnt-dinner scene, and even the falling-in-the-pool scene, and it can't help being funny, but it's funny in a very grim sort of way, and you know this isn't going to end well. It sometimes seems to be taking Adorno's famous dictum a step further and showing where social comedy fails us in a mid-20th century world that has to deal with the Holocaust and the threat of global nuclear destruction. Or maybe it's saying that only (black) comedy can deal with such a world...?

5tonikat

Interesting throes given your epigram. You've made me interested in this, I hadn't heard of it. You make me wonder what is black comedy and what is realism, but then I may be being blackly comic.

But on a lighter note, to get here i looked at your q3 epigram again and connected to it better than I had previously, I know it but it touched base today. But this epigram lovely too, I didn't know it, am working on my throes daily at the mo.

But on a lighter note, to get here i looked at your q3 epigram again and connected to it better than I had previously, I know it but it touched base today. But this epigram lovely too, I didn't know it, am working on my throes daily at the mo.

6thorold

>5 tonikat: Thanks! I'm not sure if the Hopkins epigraph worked out so well in the end - I wasn't quite happy with the line I picked and it was probably pretty opaque for anyone else who didn't know the poem well.

The Browning is a less well-known poem, but I think it's one I'm going to enjoy being made to look at repeatedly. Interesting too, to think about Browning in the dark years just after Elizabeth's death and to read it in that context. Throes indeed. And I love the little image of the earth taking its shoes and socks off to sunbathe...

(I just stopped myself in time from picking Sonnet 73 - that way lies horrible cliché!)

I'm working on the idea that it's comedy when you know the clown will stand up again after the pratfall, and realism when you're genuinely afraid he might not. Something like that.

The Browning is a less well-known poem, but I think it's one I'm going to enjoy being made to look at repeatedly. Interesting too, to think about Browning in the dark years just after Elizabeth's death and to read it in that context. Throes indeed. And I love the little image of the earth taking its shoes and socks off to sunbathe...

(I just stopped myself in time from picking Sonnet 73 - that way lies horrible cliché!)

I'm working on the idea that it's comedy when you know the clown will stand up again after the pratfall, and realism when you're genuinely afraid he might not. Something like that.

7tonikat

>6 thorold: epigraph! you know I do know the difference, but about a month ago I suddenly doubted myself and decided to look them both up, and ever since I've totally reset myself and this is no the first time I have said epigram. It probably sounds an excuse, and it is, please don't be too certain of my madness due to it.

I stopped myself from saying but it occurs to me that the Hopkins may be better sited to autumn? you may not agree. Part of me says summer can be pied too -- but autumn, well.

Oh I could have coped with sonnet 73. But your choice is good. I don't really know RB or EBB at all.

That's an interesting distinction. Something to do with faith, and subjective. It occurs to me that horror may then be when the clown is expected to stand up and doesn't. What would that make it if they stood up when not expected to? redemption? all the way to resurrection and renewal? (discovery/reminder of faith when it was most doubted?)

I stopped myself from saying but it occurs to me that the Hopkins may be better sited to autumn? you may not agree. Part of me says summer can be pied too -- but autumn, well.

Oh I could have coped with sonnet 73. But your choice is good. I don't really know RB or EBB at all.

That's an interesting distinction. Something to do with faith, and subjective. It occurs to me that horror may then be when the clown is expected to stand up and doesn't. What would that make it if they stood up when not expected to? redemption? all the way to resurrection and renewal? (discovery/reminder of faith when it was most doubted?)

8thorold

>7 tonikat: horror may then be when the clown is expected to stand up and doesn't

... but carries on as a zombie (provided a complicated set of requirements is accidentally satisfied, involving phases of the moon, lightning, religious symbols, and unseasonable weather for California).

I think you're right about "faith". In the theatre we've learnt that the clown stands up again, and we've built up a system of beliefs around that that protects us from being scared out of our wits when we see a performance (as small children sometimes are). Murdoch challenges that faith by asking us to imagine what happens if the clown falls down in the street and not on the stage...

...and I think I'm getting to the limits of this image!

... but carries on as a zombie (provided a complicated set of requirements is accidentally satisfied, involving phases of the moon, lightning, religious symbols, and unseasonable weather for California).

I think you're right about "faith". In the theatre we've learnt that the clown stands up again, and we've built up a system of beliefs around that that protects us from being scared out of our wits when we see a performance (as small children sometimes are). Murdoch challenges that faith by asking us to imagine what happens if the clown falls down in the street and not on the stage...

...and I think I'm getting to the limits of this image!

9tonikat

>8 thorold: :) - or a comet maybe, that'd do it, so says my handbook of mcguffinry (imagined) -- or maybe that would be Triffids.

10thorold

Five months in the reading, 1.68kg of paper, 1231 pages, as much a physical endurance test as an intellectual one, it would probably have been better to tackle this book when it first came out and I still had strong wrists...

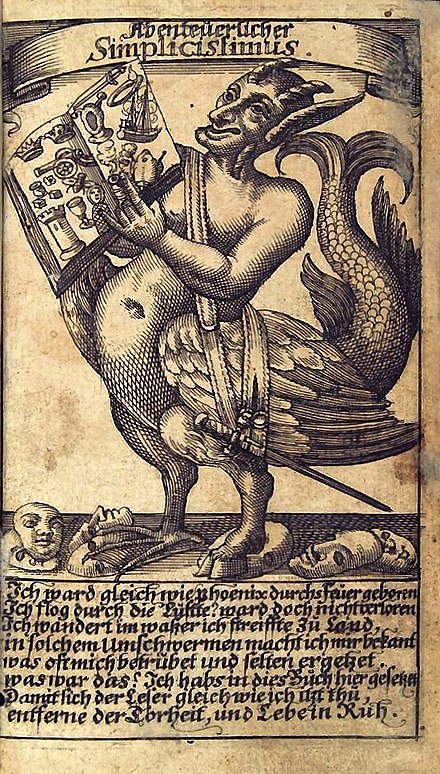

The Dutch republic : its rise, greatness, and fall, 1477-1806 (1995) by Jonathan I. Israel (UK, 1946- )

British-born Jonathan Israel currently holds a chair in history at Princeton; he was previously professor of Dutch history at UCL. As well as this book, he's known for his subsequent writings on the European Enlightenment, where he controversially gives the leading role to Spinoza.

It does what it says - a heavyweight (in every sense) overview of Dutch history from the late medieval period to Napoleon, focussing on how the Republic came into being, how it was governed, and how the political system related to developments in religious and intellectual life. Economic, military and colonial developments are covered as well, but not quite in the same level of detail.

What really interests Israel - probably to the despair of some readers, although I found it oddly fascinating - is the complicated way in which the Republic operated as a not-quite-federation of unequal and frequently disunited provinces, each of which had its own internal conflicts and divisions. In most of what I've read before about Dutch history, you only really get to hear about Holland, with the occasional passing mention of Geuzen in Zeeland and sieges in Brabant. But when you're reading Israel you also have to be aware of how the political manoeuvres in The Hague are affected by the complexities of relations between Groningen and its Ommelanden, or between the three quarters of Gelderland (I still don't know why they call them quarters if there are only three of them...). Endless fun, if you enjoy that kind of thing.

The other big element of the book is the analysis of what was going on in religion, science and philosophy (and to a lesser extent, the arts), and how it was enabled and sometimes restricted by the peculiarities of the Dutch political system. Israel makes it clear that there's a lot more to it than the standard idea that official tolerance created a kind of free market in ideas and gave the Netherlands an advantage over the repressive, absolutist rest of Europe. In fact, when it comes down to it, the religious establishment in the 17th century Netherlands had as little tolerance for divergent ideas as their protestant and catholic neighbours, and preachers were constantly campaigning to have sects other than their own shut down, books burnt, professors banned from teaching Descartes or Spinoza, and all the rest of it. There was always a strong "Voetian" element in the Dutch Reformed Church that felt that religious observance ought to be enforced by law. And it never took much to provoke the urban working classes to start an anti-Catholic riot. Where the Dutch Republic was different from the rest of Europe seems to have been in a pragmatic sense at the highest levels of government that public order mattered more than religious conformity. The state never regulated what people believed, but it could - and did - intervene to stop them causing unnecessary trouble, e.g. by publishing revolutionary ideas in Dutch, or by over-zealous preaching. Then as now, Dutch society was all about minimising overlast (nuisance). The other key thing in the 17th century Netherlands was that there was so much divergence from province to province and town to town, that you could almost always find somewhere where your views were acceptable. Spinoza moved from Amsterdam to Voorburg after he was expelled from the synagogue; professors who were too unorthodox for Leiden were generally welcomed in the rival universities at Franeker or Groningen (and vice-versa).

Whilst reading this book, I more than once had to wonder why OUP didn't split it into two (or more) volumes. This is essentially narrative history that you want to read sequentially and at leisure, not a reference book for dipping into. But a dictionary-sized book like this (1130 pages of text plus another hundred of index and bibliography) is just far too heavy to hold comfortably. My Everyman edition of Motley is about the same total number of pages in total, but in three nice, pocket-sized volumes. You could easily slip one of those into your backpack. Not that you can in any way compare Motley's chatty style and unconcealed protestant propaganda with what Israel is doing...

The Dutch republic : its rise, greatness, and fall, 1477-1806 (1995) by Jonathan I. Israel (UK, 1946- )

British-born Jonathan Israel currently holds a chair in history at Princeton; he was previously professor of Dutch history at UCL. As well as this book, he's known for his subsequent writings on the European Enlightenment, where he controversially gives the leading role to Spinoza.

It does what it says - a heavyweight (in every sense) overview of Dutch history from the late medieval period to Napoleon, focussing on how the Republic came into being, how it was governed, and how the political system related to developments in religious and intellectual life. Economic, military and colonial developments are covered as well, but not quite in the same level of detail.

What really interests Israel - probably to the despair of some readers, although I found it oddly fascinating - is the complicated way in which the Republic operated as a not-quite-federation of unequal and frequently disunited provinces, each of which had its own internal conflicts and divisions. In most of what I've read before about Dutch history, you only really get to hear about Holland, with the occasional passing mention of Geuzen in Zeeland and sieges in Brabant. But when you're reading Israel you also have to be aware of how the political manoeuvres in The Hague are affected by the complexities of relations between Groningen and its Ommelanden, or between the three quarters of Gelderland (I still don't know why they call them quarters if there are only three of them...). Endless fun, if you enjoy that kind of thing.

The other big element of the book is the analysis of what was going on in religion, science and philosophy (and to a lesser extent, the arts), and how it was enabled and sometimes restricted by the peculiarities of the Dutch political system. Israel makes it clear that there's a lot more to it than the standard idea that official tolerance created a kind of free market in ideas and gave the Netherlands an advantage over the repressive, absolutist rest of Europe. In fact, when it comes down to it, the religious establishment in the 17th century Netherlands had as little tolerance for divergent ideas as their protestant and catholic neighbours, and preachers were constantly campaigning to have sects other than their own shut down, books burnt, professors banned from teaching Descartes or Spinoza, and all the rest of it. There was always a strong "Voetian" element in the Dutch Reformed Church that felt that religious observance ought to be enforced by law. And it never took much to provoke the urban working classes to start an anti-Catholic riot. Where the Dutch Republic was different from the rest of Europe seems to have been in a pragmatic sense at the highest levels of government that public order mattered more than religious conformity. The state never regulated what people believed, but it could - and did - intervene to stop them causing unnecessary trouble, e.g. by publishing revolutionary ideas in Dutch, or by over-zealous preaching. Then as now, Dutch society was all about minimising overlast (nuisance). The other key thing in the 17th century Netherlands was that there was so much divergence from province to province and town to town, that you could almost always find somewhere where your views were acceptable. Spinoza moved from Amsterdam to Voorburg after he was expelled from the synagogue; professors who were too unorthodox for Leiden were generally welcomed in the rival universities at Franeker or Groningen (and vice-versa).

Whilst reading this book, I more than once had to wonder why OUP didn't split it into two (or more) volumes. This is essentially narrative history that you want to read sequentially and at leisure, not a reference book for dipping into. But a dictionary-sized book like this (1130 pages of text plus another hundred of index and bibliography) is just far too heavy to hold comfortably. My Everyman edition of Motley is about the same total number of pages in total, but in three nice, pocket-sized volumes. You could easily slip one of those into your backpack. Not that you can in any way compare Motley's chatty style and unconcealed protestant propaganda with what Israel is doing...

11dchaikin

A mental and physical workout? Sounds fascinating. I know very little about Dutch history, but I’ve always been curious how it got to be that kind of place.

12thorold

>11 dchaikin: Go for it! I’m sure it would be a breeze for someone used to swinging a geologist’s hammer. Simon Schama’s The embarrassment of riches is very good too, if you’re more interested in the culture and less in day to day politics.

13thorold

This is one of the pile of random Simenon paperbacks I picked up from the charity shop a few years ago, and which has been on holiday with me a few times "in case the e-reader stops working". I finally got fed up with seeing it on the TBR shelf...

La mort d'Auguste (1966, The old man dies) by Georges Simenon (France, 1903-1989)

Antoine and his father Auguste have worked hard for twenty years to build up what was just a market-workers' bistro outside Les Halles into a profitable and fashionable restaurant with two stars in Michelin. But when Auguste has a stroke and dies unexpectedly, Antoine realises that he has never talked to his father - still a suspicious old peasant at heart, even after more than sixty years in Paris - about wills or inheritance, and he doesn't even know what his father has done with his share of the earnings from the business. A question that Antoine's two impecunious brothers would like to have answered fairly promptly, and which even leads them to suspect Antoine of cheating them...

This counts as one of Simenon's "straight" novels, not a Maigret or even really a crime story in the usual sense, and it's not the technical question of "where's the money?" that drives the plot, but the way in which Antoine has to find a way to handle this annoying (but potentially crucial) irrelevance at the same time as coming face to face with the arbitrary brutality of death and dealing with the normal emotional stresses of the loss of a parent. And, of course, it being Simenon, we get some brief but very telling little glimpses into the restaurant trade, the mentality of Auvergnats who migrated to Paris, and the lost world of Les Halles, already designated for relocation and redevelopment at the time of writing (it actually happened in 1971).

La mort d'Auguste (1966, The old man dies) by Georges Simenon (France, 1903-1989)

Antoine and his father Auguste have worked hard for twenty years to build up what was just a market-workers' bistro outside Les Halles into a profitable and fashionable restaurant with two stars in Michelin. But when Auguste has a stroke and dies unexpectedly, Antoine realises that he has never talked to his father - still a suspicious old peasant at heart, even after more than sixty years in Paris - about wills or inheritance, and he doesn't even know what his father has done with his share of the earnings from the business. A question that Antoine's two impecunious brothers would like to have answered fairly promptly, and which even leads them to suspect Antoine of cheating them...

This counts as one of Simenon's "straight" novels, not a Maigret or even really a crime story in the usual sense, and it's not the technical question of "where's the money?" that drives the plot, but the way in which Antoine has to find a way to handle this annoying (but potentially crucial) irrelevance at the same time as coming face to face with the arbitrary brutality of death and dealing with the normal emotional stresses of the loss of a parent. And, of course, it being Simenon, we get some brief but very telling little glimpses into the restaurant trade, the mentality of Auvergnats who migrated to Paris, and the lost world of Les Halles, already designated for relocation and redevelopment at the time of writing (it actually happened in 1971).

14FlorenceArt

>10 thorold: "Where the Dutch Republic was different from the rest of Europe seems to have been in a pragmatic sense at the highest levels of government that public order mattered more than religious conformity."

I suppose it’s mostly because I’m re-reading a Discworld novel, but I couldn’t help thinking of Ank-Mopork and Lord Vetinari as I read this.

The Dutch Republic sounds interesting but intimidating. The Embarassment of Riches sounds even better.

I suppose it’s mostly because I’m re-reading a Discworld novel, but I couldn’t help thinking of Ank-Mopork and Lord Vetinari as I read this.

The Dutch Republic sounds interesting but intimidating. The Embarassment of Riches sounds even better.

15thorold

And the next stage of my stroll through the work of eccentric Swiss genius Robert Walser:

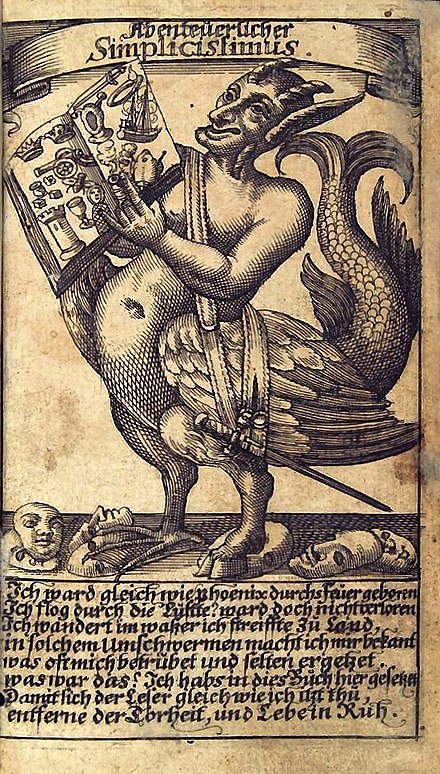

Der Spaziergang, Prosastücke und Kleine Prosa (originally published 1916-1917; in the complete works 1985; The walk, etc.) by Robert Walser (Switzerland, 1878-1956)

Frustrated at his inability to find a way to follow up the modest success of his three novels, Walser left Berlin in March 1913 and returned to Switzerland, to settle in Biel for the next few years. He continued to publish pieces in newspapers and magazines, and he even won a literary prize for the last of his collections published in Germany, Kleine Dichtungen (the money was trapped in a German bank account and wiped out by inflation before he was able to touch it), but the outbreak of war interrupted his relations with his German publishers. In 1916 he was approached independently by three different Swiss publishers looking to include him in their catalogue of home-grown authors, which resulted in the publication within a short space of time of the novella-length Der Spaziergang, and two collections of short pieces, the pamphlet Prosastücke and the book-length Kleine Prosa. These three are brought together in Vol.5 of the Suhrkamp complete works, but you might find other combinations in translations.

Der Spaziergang sets the tone for all the pieces in the book - superficially a very simple account of a stroll the narrator takes on a sunny day in the Swiss town where he lives. He comments on shops and people he passes, reflects on the weather and the scenery, talks about a couple of encounters that sound significant but don't seem to lead to anything, and describes a lunch he's been invited to and a few small errands he has reserved for the afternoon (posting a letter, a fitting with the tailor, an appointment at the town hall). It's all set up in a very modest, self-deprecating and ironic tone, but we soon realise that there's something else going on under the surface. The prose defies the apparently realistic context by looping away in grand, rhythmic structures that often take the reader's breath away. The conversations the narrator describes clearly aren't meant to be taken as realistic accounts of what he has said (or what anyone could get away with saying in real life), but rather what he wishes he could have said, or what he was thinking when he said whatever he did actually say. This creates an uneasy sense of disconnection, alienation, from the banal, ordinary events of life. Images and chance remarks keep reminding us that there's a horrific war going on just offstage. Although all the explicit references are to German Romanticism of the Brentano era, this is unmistakably the voice of modernism - you can't help reading Walser's strolling writer posting his letters, eating his lunch and worrying about his tailor as a contemporary (or precursor) of Bloom wandering through Dublin, Mrs Dalloway buying her flowers or Prufrock walking on the beach.

In the two collections of prose pieces - most of which slide between categories like essay, sketch, story, memoir and review in undefinable ways - there's a similar sense of disconnection between the writer and the world, and a slightly amused astonishment at how strange everything is. We read pieces that are about nothing but themselves and the language they are made of, pieces about great writers (Dickens is chastised for being so good at what he did that he discourages all others from even trying to write), about a sausage, about odd characters who reject social norms, about fairy-tale-like incidents, and very frequently about young writers with various different names (in one case three different names in the same story) who work in offices or factories, become domestic servants, or live in isolation and penury in the suburbs and try to write - all things that Walser had done at various points in his career. Fascinating and delightful!

Der Spaziergang, Prosastücke und Kleine Prosa (originally published 1916-1917; in the complete works 1985; The walk, etc.) by Robert Walser (Switzerland, 1878-1956)

Frustrated at his inability to find a way to follow up the modest success of his three novels, Walser left Berlin in March 1913 and returned to Switzerland, to settle in Biel for the next few years. He continued to publish pieces in newspapers and magazines, and he even won a literary prize for the last of his collections published in Germany, Kleine Dichtungen (the money was trapped in a German bank account and wiped out by inflation before he was able to touch it), but the outbreak of war interrupted his relations with his German publishers. In 1916 he was approached independently by three different Swiss publishers looking to include him in their catalogue of home-grown authors, which resulted in the publication within a short space of time of the novella-length Der Spaziergang, and two collections of short pieces, the pamphlet Prosastücke and the book-length Kleine Prosa. These three are brought together in Vol.5 of the Suhrkamp complete works, but you might find other combinations in translations.

Der Spaziergang sets the tone for all the pieces in the book - superficially a very simple account of a stroll the narrator takes on a sunny day in the Swiss town where he lives. He comments on shops and people he passes, reflects on the weather and the scenery, talks about a couple of encounters that sound significant but don't seem to lead to anything, and describes a lunch he's been invited to and a few small errands he has reserved for the afternoon (posting a letter, a fitting with the tailor, an appointment at the town hall). It's all set up in a very modest, self-deprecating and ironic tone, but we soon realise that there's something else going on under the surface. The prose defies the apparently realistic context by looping away in grand, rhythmic structures that often take the reader's breath away. The conversations the narrator describes clearly aren't meant to be taken as realistic accounts of what he has said (or what anyone could get away with saying in real life), but rather what he wishes he could have said, or what he was thinking when he said whatever he did actually say. This creates an uneasy sense of disconnection, alienation, from the banal, ordinary events of life. Images and chance remarks keep reminding us that there's a horrific war going on just offstage. Although all the explicit references are to German Romanticism of the Brentano era, this is unmistakably the voice of modernism - you can't help reading Walser's strolling writer posting his letters, eating his lunch and worrying about his tailor as a contemporary (or precursor) of Bloom wandering through Dublin, Mrs Dalloway buying her flowers or Prufrock walking on the beach.

In the two collections of prose pieces - most of which slide between categories like essay, sketch, story, memoir and review in undefinable ways - there's a similar sense of disconnection between the writer and the world, and a slightly amused astonishment at how strange everything is. We read pieces that are about nothing but themselves and the language they are made of, pieces about great writers (Dickens is chastised for being so good at what he did that he discourages all others from even trying to write), about a sausage, about odd characters who reject social norms, about fairy-tale-like incidents, and very frequently about young writers with various different names (in one case three different names in the same story) who work in offices or factories, become domestic servants, or live in isolation and penury in the suburbs and try to write - all things that Walser had done at various points in his career. Fascinating and delightful!

16thorold

>14 FlorenceArt: I couldn’t help thinking of Ank-Mopork and Lord Vetinari

Yes! Maybe Pratchett had something like that in mind. Not that anyone in the Republic was ever able to exercise the amount of personal power that Vetinari seems to have. Even the most competent and devious Stadholders (William I, Maurits and William III) had to mix coercion with a lot of lobbying and bribing to get what they wanted, and even then it didn't always work for them.

Yes! Maybe Pratchett had something like that in mind. Not that anyone in the Republic was ever able to exercise the amount of personal power that Vetinari seems to have. Even the most competent and devious Stadholders (William I, Maurits and William III) had to mix coercion with a lot of lobbying and bribing to get what they wanted, and even then it didn't always work for them.

17thorold

It's been a good weekend for finishing things off...

No. 6 in the Zolathon:

Son Excellence Eugène Rougon (1876; His Excellency) by Emile Zola (France, 1840-1902)

This is a sort of counterpoise to La Curée: we're back in Paris, in the second half of the 1850s, but the focus is on national rather than local politics, and the central character this time is Aristide's brother Eugène Rougon, a career politician in Napoleon III's government, with the highly desirable quality in a man of his profession that he can bounce back almost effortlessly into office from the depths of whatever scandal he lands in.

Astonishingly, for once, Zola manages to put together a plot without any doomed under-age sexual relationships in it: the main axis of erotic tension this time is between Eugène and the beautiful Clorinde, a femme fatale clawing her way up into Second Empire society from nowhere. Since they are both far more turned on by power than by conventional sexual allure, and neither of them wants to concede an inch to the other, their relationship is far from straightforward, but Zola wouldn't be Zola without a magnificently symbolic sex-scene, so at one point in the story they are allowed to get hands-on with a horsewhip in the riding-stables. Zola would definitely have enjoyed the possibilities of cinema.

A narrative trick that Zola re-uses from La fortune des Rougons is to tell us a lot of the story through a group of minor characters, here Eugène's hangers-on, the little people who spread propaganda on his behalf in exchange for the prospect of favours when he gets into office, in a less well regulated version of the 18th century clientage system. And of course it is usually the greed and ingratitude of these people that push him into over-reaching and get him into trouble so that he has to start clawing his way back again.

The main point of the book, though, is to show us the corrupt and hypocritical workings of government under Napoleon III: We open with the puppet Assembly of 1856, in an atmosphere of the deepest possible tedium and pointlessness, voting through a huge budget allocation for the baptismal ceremonies for the Emperor's infant son; there is more high-level royal tedium in a hunting party at Compiègne (Zola turns out to be surprisingly good at conveying boredom entertainingly); We move forward to the Orsini assassination plot of 1858, which gives Eugène another chance to come back into power, this time as the minister charged with implementing repressive anti-terrorism measures; There's a glorious set-piece cabinet meeting at which Eugène argues convincingly that only a policy of hardline repression and a climate of fear can sustain an absolutist empire in 19th century Europe - possibly Eugène is the only person in the room who misses the obvious conclusion that this is an argument against absolutism, not one in favour of repression - and then digs himself in deeper by condemning a "subversive" popular education book which - again, Zola doesn't tell us in so many words, but we can see it dawning on everyone around the table and the Emperor trying to keep a straight face - is a transparent rip-off of the Emperor's famous 1844 socialist pamphlet, Extinction du paupérisme; And we close with another, far less tedious but equally pointless, session of the Assembly, in which the Bonapartist delegates get to shout insults at the tiny Opposition group who are attempting to point out the hollowness of the 1861 reforms. And who is the government spokesman? None other than our old friend E. Rougon...

No. 6 in the Zolathon:

Son Excellence Eugène Rougon (1876; His Excellency) by Emile Zola (France, 1840-1902)

This is a sort of counterpoise to La Curée: we're back in Paris, in the second half of the 1850s, but the focus is on national rather than local politics, and the central character this time is Aristide's brother Eugène Rougon, a career politician in Napoleon III's government, with the highly desirable quality in a man of his profession that he can bounce back almost effortlessly into office from the depths of whatever scandal he lands in.

Astonishingly, for once, Zola manages to put together a plot without any doomed under-age sexual relationships in it: the main axis of erotic tension this time is between Eugène and the beautiful Clorinde, a femme fatale clawing her way up into Second Empire society from nowhere. Since they are both far more turned on by power than by conventional sexual allure, and neither of them wants to concede an inch to the other, their relationship is far from straightforward, but Zola wouldn't be Zola without a magnificently symbolic sex-scene, so at one point in the story they are allowed to get hands-on with a horsewhip in the riding-stables. Zola would definitely have enjoyed the possibilities of cinema.

A narrative trick that Zola re-uses from La fortune des Rougons is to tell us a lot of the story through a group of minor characters, here Eugène's hangers-on, the little people who spread propaganda on his behalf in exchange for the prospect of favours when he gets into office, in a less well regulated version of the 18th century clientage system. And of course it is usually the greed and ingratitude of these people that push him into over-reaching and get him into trouble so that he has to start clawing his way back again.

The main point of the book, though, is to show us the corrupt and hypocritical workings of government under Napoleon III: We open with the puppet Assembly of 1856, in an atmosphere of the deepest possible tedium and pointlessness, voting through a huge budget allocation for the baptismal ceremonies for the Emperor's infant son; there is more high-level royal tedium in a hunting party at Compiègne (Zola turns out to be surprisingly good at conveying boredom entertainingly); We move forward to the Orsini assassination plot of 1858, which gives Eugène another chance to come back into power, this time as the minister charged with implementing repressive anti-terrorism measures; There's a glorious set-piece cabinet meeting at which Eugène argues convincingly that only a policy of hardline repression and a climate of fear can sustain an absolutist empire in 19th century Europe - possibly Eugène is the only person in the room who misses the obvious conclusion that this is an argument against absolutism, not one in favour of repression - and then digs himself in deeper by condemning a "subversive" popular education book which - again, Zola doesn't tell us in so many words, but we can see it dawning on everyone around the table and the Emperor trying to keep a straight face - is a transparent rip-off of the Emperor's famous 1844 socialist pamphlet, Extinction du paupérisme; And we close with another, far less tedious but equally pointless, session of the Assembly, in which the Bonapartist delegates get to shout insults at the tiny Opposition group who are attempting to point out the hollowness of the 1861 reforms. And who is the government spokesman? None other than our old friend E. Rougon...

18thorold

I've read far too little of J.M. Coetzee's work - possibly because I'm always a little shy of taking on writers who come so very heavily recommended (a Nobel, two Bookers, and all the rest, plus a large coterie of Dutch and South African Coetzee fans who keep lending me his books with meaningful looks...). And at least one of the ones I have read (Disgrace) I didn't like all that much. But now the South African member of our book club has manoeuvred me into a corner by craftily proposing Summertime as our next book, knowing full well that I would never read the third volume of a trilogy without reading the other two as well... :-)

Scenes from Provincial Life: Boyhood, Youth, Summertime (parts 1997, 2002, 2009; combined edition 2011) by J. M. Coetzee (South Africa, 1940- )

J.M. Coetzee has a reputation as an extremely modest, publicity-averse sort of writer - and of course he can afford to be: if you have that many trophies on the mantlepiece, you don't exactly need to go to small-town book-signings every day. But even modest writers usually manage to boast a little bit about their achievements in their memoirs, to look back with amusement at their youthful struggles from the olympian heights of where they are now, and of course to take it for granted that any vengeful ex-lovers will save the embarrassing revelations for posthumous biographers.

Not so Coetzee, apparently: his chief concern in these three lightly fictionalised fragments of autobiography seems to be to show us all the ways in which he falls short of his own standards for what a Coetzee, an Afrikaner, a writer and a human being should be. He shows us his subject "John Coetzee" as a boy at school, as a student and then an exile in England, working in the computer industry, and then back in 70s South Africa as a teacher and academic who has yet to make his mark as a writer. In the first two parts the form is relatively conventional - there are plenty of other famous memoirs in which the author writes about himself in the third person and in the present tense - the only real peculiarity being the absolute exclusion of any kind of explicit hindsight. Coetzee-the-narrator never lets us spot him taking advantage of the intervening years to put events into context or add information we know John-the-subject couldn't have had access to at the time. That gives the text a lot of the rawness and immediacy of a novel, preventing us from standing back and saying "Ah well, that was before...".

Boyhood is mostly about the young John attempting to work out the rules of the complex world he lives in, constantly frustrated by his parents' inability to be "normal" - they speak English, not Afrikaans, they don't go to church, they don't vote for the National party, etc., but they have an Afrikaner name, and they live in the same squalor as their Afrikaner neighbours, not up in the posh part of town like the "real" English and the Jews... Then, when he goes to his grandparents' farm in the Karoo, he feels utterly drawn towards this landscape, even though he knows he has no sort of right to it.

Youth has John at a stage where he knows from everything he's read and dreamed that it's only a matter of days or weeks before the Significant Thing must happen - he will meet the person he wants to spend the rest of his life with and/or find the inspiration to write the great poem/story/novel he's destined to produce and/or discover the professional satisfaction in computer programming that's been eluding him so far and/or take the world of literature by storm with the insights in his MA dissertation on Ford Maddox Ford. But things go on not happening. Affairs with women are unsatisfactory and are usually ended by him behaving badly in some way; his writing is getting nowhere; Ford, apart from the great novels he already knew, turns out to be a bore; and computers are taking John to places where he doesn't really want to be, not least to AWRE Aldermaston.

Then in Summertime Coetzee changes course to play with a quite different and much more dangerous formal approach. He kills off his subject and hands the narration over to Vincent, a clumsy academic and not very good writer, who is compiling material for a biography of "John Coetzee before his breakthrough". As in the last part of Iris Murdoch's The Black Prince, one unreliable narrator is replaced by a whole bunch of others, as Vincent interviews four women and a man who were close to John in one way or another during the first years after his return to South Africa - a married woman with whom he had an affair, one of his female cousins from the Karoo, a Brazilian dance teacher who may have been the inspiration for the woman in Foe, and two faculty colleagues, one male and one female. The whole is topped and tailed by fragments of John's notes presumed to be from an abandoned attempt at a third volume of memoirs. And of course all of it is set up to show us John's repeated failures (as far as the witnesses know) to connect in the wholehearted way he would like to have done with his family, students, his lovers and with the broken culture of the broken country he grew up in.

It's often extremely funny, but it makes painful reading. And it - of course - doesn't manage to answer the question it poses, how someone who seems to be damaged in ways that prevent him from getting to grips in real life with what it means to be a human being could ever be able to write novels that purport to tell us just that. Probably, we have to look into ourselves and decide that no-one could ever really attain the standard of humanness that Coetzee sets himself - as one of his characters points out, Gandhi couldn't dance.

Scenes from Provincial Life: Boyhood, Youth, Summertime (parts 1997, 2002, 2009; combined edition 2011) by J. M. Coetzee (South Africa, 1940- )

J.M. Coetzee has a reputation as an extremely modest, publicity-averse sort of writer - and of course he can afford to be: if you have that many trophies on the mantlepiece, you don't exactly need to go to small-town book-signings every day. But even modest writers usually manage to boast a little bit about their achievements in their memoirs, to look back with amusement at their youthful struggles from the olympian heights of where they are now, and of course to take it for granted that any vengeful ex-lovers will save the embarrassing revelations for posthumous biographers.

Not so Coetzee, apparently: his chief concern in these three lightly fictionalised fragments of autobiography seems to be to show us all the ways in which he falls short of his own standards for what a Coetzee, an Afrikaner, a writer and a human being should be. He shows us his subject "John Coetzee" as a boy at school, as a student and then an exile in England, working in the computer industry, and then back in 70s South Africa as a teacher and academic who has yet to make his mark as a writer. In the first two parts the form is relatively conventional - there are plenty of other famous memoirs in which the author writes about himself in the third person and in the present tense - the only real peculiarity being the absolute exclusion of any kind of explicit hindsight. Coetzee-the-narrator never lets us spot him taking advantage of the intervening years to put events into context or add information we know John-the-subject couldn't have had access to at the time. That gives the text a lot of the rawness and immediacy of a novel, preventing us from standing back and saying "Ah well, that was before...".

Boyhood is mostly about the young John attempting to work out the rules of the complex world he lives in, constantly frustrated by his parents' inability to be "normal" - they speak English, not Afrikaans, they don't go to church, they don't vote for the National party, etc., but they have an Afrikaner name, and they live in the same squalor as their Afrikaner neighbours, not up in the posh part of town like the "real" English and the Jews... Then, when he goes to his grandparents' farm in the Karoo, he feels utterly drawn towards this landscape, even though he knows he has no sort of right to it.

Youth has John at a stage where he knows from everything he's read and dreamed that it's only a matter of days or weeks before the Significant Thing must happen - he will meet the person he wants to spend the rest of his life with and/or find the inspiration to write the great poem/story/novel he's destined to produce and/or discover the professional satisfaction in computer programming that's been eluding him so far and/or take the world of literature by storm with the insights in his MA dissertation on Ford Maddox Ford. But things go on not happening. Affairs with women are unsatisfactory and are usually ended by him behaving badly in some way; his writing is getting nowhere; Ford, apart from the great novels he already knew, turns out to be a bore; and computers are taking John to places where he doesn't really want to be, not least to AWRE Aldermaston.

Then in Summertime Coetzee changes course to play with a quite different and much more dangerous formal approach. He kills off his subject and hands the narration over to Vincent, a clumsy academic and not very good writer, who is compiling material for a biography of "John Coetzee before his breakthrough". As in the last part of Iris Murdoch's The Black Prince, one unreliable narrator is replaced by a whole bunch of others, as Vincent interviews four women and a man who were close to John in one way or another during the first years after his return to South Africa - a married woman with whom he had an affair, one of his female cousins from the Karoo, a Brazilian dance teacher who may have been the inspiration for the woman in Foe, and two faculty colleagues, one male and one female. The whole is topped and tailed by fragments of John's notes presumed to be from an abandoned attempt at a third volume of memoirs. And of course all of it is set up to show us John's repeated failures (as far as the witnesses know) to connect in the wholehearted way he would like to have done with his family, students, his lovers and with the broken culture of the broken country he grew up in.

It's often extremely funny, but it makes painful reading. And it - of course - doesn't manage to answer the question it poses, how someone who seems to be damaged in ways that prevent him from getting to grips in real life with what it means to be a human being could ever be able to write novels that purport to tell us just that. Probably, we have to look into ourselves and decide that no-one could ever really attain the standard of humanness that Coetzee sets himself - as one of his characters points out, Gandhi couldn't dance.

19thorold

There still seem to be two or three Muriel Sparks I haven't (re-)read in the last couple of years - time for another one:

The ballad of Peckham Rye (1960) by Muriel Spark (UK, 1918-2006)

This is one of Spark's crazier novels, published the year before Miss Jean Brodie. It is set in a working-class district of South London, and the story is all about factory workers and their bosses, dances, nights at the pub, fights about girls, petty crime, adultery, saving up to get married, sneaking lovers past the landlady, etc., so it's clearly setting itself up as though it's in the same genre as the novels and plays of contemporaries like Alan Sillitoe and Stan Barstow. But this is most definitely not grittily realistic angry-young-man fiction, it's more like a sophisticated, playful parody of its conventions. No-one here is the victim of anything other than their own moral limitations. The violence, when it occurs, is as balletic as anything in West Side Story, and the story line is constantly wavering at the very edge of realism.

The comic disturbing agent in the plot is the Scotsman Dougal Douglas, who often seems to be Psmith playing the part of Donald Farfrae. We're in Wodehouse country, after all: Peckham Rye is just down the road from East Dulwich. Douglas is an agent of chaos who enjoys inserting himself into social situations and interfering at random. Apparently he does this simply to see what will happen, as Psmith did, but he himself also enjoys dropping hints that he is an incarnation of the Devil, an interpretation Spark does nothing to confirm or deny (Peckham Rye is also William Blake country...). In the course of the story he completely undermines employee morale in two local factories where he's been brought into the Personnel department as an "Arts man" with an ill-defined mission to tackle disaffection and absenteeism (so ill-defined that he's able to hold the same job simultaneously in both companies without his bosses noticing anything); he sends several managers into breakdowns or depression; he sabotages a long-planned wedding, and he's indirectly responsible for at least two deaths. And he has time to adapt his adventures to fit a ghosted autobiography he's writing for an elderly actress...

Entertaining in a very Sparkish way, but I'm not sure if it does anything beyond that. There may well be a serious moral tale buried under all that exuberant chaos, but if there is, it's so convoluted and ambiguous that few readers are going to bother to work it out.

The ballad of Peckham Rye (1960) by Muriel Spark (UK, 1918-2006)

This is one of Spark's crazier novels, published the year before Miss Jean Brodie. It is set in a working-class district of South London, and the story is all about factory workers and their bosses, dances, nights at the pub, fights about girls, petty crime, adultery, saving up to get married, sneaking lovers past the landlady, etc., so it's clearly setting itself up as though it's in the same genre as the novels and plays of contemporaries like Alan Sillitoe and Stan Barstow. But this is most definitely not grittily realistic angry-young-man fiction, it's more like a sophisticated, playful parody of its conventions. No-one here is the victim of anything other than their own moral limitations. The violence, when it occurs, is as balletic as anything in West Side Story, and the story line is constantly wavering at the very edge of realism.

The comic disturbing agent in the plot is the Scotsman Dougal Douglas, who often seems to be Psmith playing the part of Donald Farfrae. We're in Wodehouse country, after all: Peckham Rye is just down the road from East Dulwich. Douglas is an agent of chaos who enjoys inserting himself into social situations and interfering at random. Apparently he does this simply to see what will happen, as Psmith did, but he himself also enjoys dropping hints that he is an incarnation of the Devil, an interpretation Spark does nothing to confirm or deny (Peckham Rye is also William Blake country...). In the course of the story he completely undermines employee morale in two local factories where he's been brought into the Personnel department as an "Arts man" with an ill-defined mission to tackle disaffection and absenteeism (so ill-defined that he's able to hold the same job simultaneously in both companies without his bosses noticing anything); he sends several managers into breakdowns or depression; he sabotages a long-planned wedding, and he's indirectly responsible for at least two deaths. And he has time to adapt his adventures to fit a ghosted autobiography he's writing for an elderly actress...

Entertaining in a very Sparkish way, but I'm not sure if it does anything beyond that. There may well be a serious moral tale buried under all that exuberant chaos, but if there is, it's so convoluted and ambiguous that few readers are going to bother to work it out.

20SassyLassy

>10 thorold: "... known for his subsequent writings on the European Enlightenment, where he controversially gives the leading role to Spinoza"

And why not?! Seriously though, could you elaborate a little - I am always interested in Spinoza.

>17 thorold: You've definitely captured this one. Unfortunately I rely on translations, so had to wait for this year for a good one. I read this in July (and I'm even further behind in my reading post). Although the reading was definitely out of the suggested reading order, it didn't seem to make any difference, although anyone reading it should definitely read L'Argent and La Curée too.

>18 thorold: Wonderful look at Coetzee.

And why not?! Seriously though, could you elaborate a little - I am always interested in Spinoza.

>17 thorold: You've definitely captured this one. Unfortunately I rely on translations, so had to wait for this year for a good one. I read this in July (and I'm even further behind in my reading post). Although the reading was definitely out of the suggested reading order, it didn't seem to make any difference, although anyone reading it should definitely read L'Argent and La Curée too.

>18 thorold: Wonderful look at Coetzee.

21thorold

>20 SassyLassy: could you elaborate...?

Even though I’ve survived years of presenting shaky data to rooms full of sceptical managers since then, that phrase still manages to call up the awful sensation you get in tutorials when you’re reading an essay out and you realise from the look on your tutor’s face that you’ve just said something more than usually sweeping and implausible, and he knows you don’t have any authorities in reserve to back it up with...

I haven’t read Israel’s books on the Enlightenment (yet). What I gather from the abstracts and from Israel’s Wikipedia page is that the controversial issue is how he sees relative moderates like Locke and Montesquieu as a kind of evolutionary dead end, and traces all the Enlightenment ideas that really changed the world back to the most radical thinkers, especially Spinoza. But that’s probably a huge over-simplification of what he actually says.

Zola: I agree, reading order rarely seems to matter much, apart from the first and last books. We go back and forth in time anyway. I noticed that, whilst Eugène was mentioned a couple of times in La Curée, Aristide didn’t appear at all in this book, and the rebuilding of Paris was only mentioned a couple of times rather indirectly.

Even though I’ve survived years of presenting shaky data to rooms full of sceptical managers since then, that phrase still manages to call up the awful sensation you get in tutorials when you’re reading an essay out and you realise from the look on your tutor’s face that you’ve just said something more than usually sweeping and implausible, and he knows you don’t have any authorities in reserve to back it up with...

I haven’t read Israel’s books on the Enlightenment (yet). What I gather from the abstracts and from Israel’s Wikipedia page is that the controversial issue is how he sees relative moderates like Locke and Montesquieu as a kind of evolutionary dead end, and traces all the Enlightenment ideas that really changed the world back to the most radical thinkers, especially Spinoza. But that’s probably a huge over-simplification of what he actually says.

Zola: I agree, reading order rarely seems to matter much, apart from the first and last books. We go back and forth in time anyway. I noticed that, whilst Eugène was mentioned a couple of times in La Curée, Aristide didn’t appear at all in this book, and the rebuilding of Paris was only mentioned a couple of times rather indirectly.

22dchaikin

>18 thorold: you might relay to the South African member of your book club that I enjoyed these reviews of Coetzee.

23SassyLassy

>21 thorold: It was kind of tongue in cheek, knowing that sensation all too well myself, but I truly was interested in the idea of Spinoza having such an effect. Just read the Margaret Jacob review in the LRB, "Spinoza Got It".

24thorold

>23 SassyLassy: Yes, Spinoza's definitely very interesting. I keep meaning to follow up on Steven Nadler's A book forged in hell, which I read a couple of years ago, but haven't got very far yet.

Just such a nuisance that whenever you ask for his work in a bookshop you risk getting handed Florence Craye's latest novel instead...

Not the immortal (but elusive) Spindrift, but still a book I came across and got sucked into when I was looking for something quite different.

Old Filth (2004) by Jane Gardam (UK, 1928- )

Jane Gardam has been writing fiction for both adults and children since the seventies, and there are nearly 2000 copies of this book on LT, but for some reason I never seem to have come across her before. Maybe I was just a year or two too old to notice her children's books when they started to become known? My loss, anyway.

It took me a little while to get properly involved with this novel, in which an elderly, retired colonial judge looks back on a life that is quite different from the smooth ride everyone else assumes he must have had.

Gardam is not an aggressively witty or sophisticated writer, and she doesn't do much to haul the reader in at the outset. Her favoured technique seems to be to sneak in towards something that will give us a deeper insight into her characters, but then turn back just before she gets there, leaving us dangling until the next opportunity. An approach that can be very effective, but makes this read almost more like a novel of the 1950s than one written just over a decade ago. This slightly archaic feeling is reinforced by the subject-matter, of course: there are strong echoes of Elizabeth Taylor's Mrs Palfrey in Gardam's tough-but-emotionally-scarred survivors of upper-class colonial childhoods, and of course (as she acknowledges) the voice of the most famously damaged Raj child, Kipling, is never far away. But Gardam brings in plenty of material that goes beyond the obvious - having been married to a QC for many years she is able to write about ageing barristers without making it sound like a pastiche of Rumpole (not that John Mortimer would ever take on a judge as a sympathetic main character!), and the cameo appearance of Queen Mary is a rather splendid touch. I wouldn't quite put in on my list of 100 greatest books, but it does go a step or two beyond being merely entertaining and well-researched.

Just such a nuisance that whenever you ask for his work in a bookshop you risk getting handed Florence Craye's latest novel instead...

Not the immortal (but elusive) Spindrift, but still a book I came across and got sucked into when I was looking for something quite different.

Old Filth (2004) by Jane Gardam (UK, 1928- )

Jane Gardam has been writing fiction for both adults and children since the seventies, and there are nearly 2000 copies of this book on LT, but for some reason I never seem to have come across her before. Maybe I was just a year or two too old to notice her children's books when they started to become known? My loss, anyway.

It took me a little while to get properly involved with this novel, in which an elderly, retired colonial judge looks back on a life that is quite different from the smooth ride everyone else assumes he must have had.

Gardam is not an aggressively witty or sophisticated writer, and she doesn't do much to haul the reader in at the outset. Her favoured technique seems to be to sneak in towards something that will give us a deeper insight into her characters, but then turn back just before she gets there, leaving us dangling until the next opportunity. An approach that can be very effective, but makes this read almost more like a novel of the 1950s than one written just over a decade ago. This slightly archaic feeling is reinforced by the subject-matter, of course: there are strong echoes of Elizabeth Taylor's Mrs Palfrey in Gardam's tough-but-emotionally-scarred survivors of upper-class colonial childhoods, and of course (as she acknowledges) the voice of the most famously damaged Raj child, Kipling, is never far away. But Gardam brings in plenty of material that goes beyond the obvious - having been married to a QC for many years she is able to write about ageing barristers without making it sound like a pastiche of Rumpole (not that John Mortimer would ever take on a judge as a sympathetic main character!), and the cameo appearance of Queen Mary is a rather splendid touch. I wouldn't quite put in on my list of 100 greatest books, but it does go a step or two beyond being merely entertaining and well-researched.

25thorold

>20 SassyLassy: >22 dchaikin: Coetzee

- I’m looking forward to discussing it with the book club in a couple of weeks. I feel I only scraped the surface with what I wrote there. There’s just so much going on that presses buttons for me. The whole bilingualism thing, for instance, or the way he keeps both the interest in literature and that in maths and computers going, but also feels it’s a weakness in himself not to be able to decide for one or the other. And lots of other stuff...

- I’m looking forward to discussing it with the book club in a couple of weeks. I feel I only scraped the surface with what I wrote there. There’s just so much going on that presses buttons for me. The whole bilingualism thing, for instance, or the way he keeps both the interest in literature and that in maths and computers going, but also feels it’s a weakness in himself not to be able to decide for one or the other. And lots of other stuff...

26dchaikin

"Her favoured technique seems to be to sneak in towards something that will give us a deeper insight into her characters, but then turn back just before she gets there, leaving us dangling until the next opportunity."

Enjoyed your Gardam review. And it looks like there may be more Coetzee in your future.

Enjoyed your Gardam review. And it looks like there may be more Coetzee in your future.

27lisapeet

>24 thorold: I love Gardam's oblique approach to her characters and their lives in that book. I haven't read the next two in the series (The Man in the Wooden Hat and Last Friends), in part I think because I anticipate some slight disappointment when they're stacked up against the first. It's been long enough since I read it, though, that maybe they wouldn't suffer by comparison. I did really like that first one, which is probably in my top 100.

28thorold

>27 lisapeet: Well, as it happens, I had an unexpected day of idleness today, so I went right on and read the other two...

The Man in the Wooden Hat (2009) by Jane Gardam (UK, 1928- )

Last friends (2013) by Jane Gardam (UK, 1928- )

The storyline of Old Filth doesn't seem to offer much scope for sequels - it's pretty much a cradle-to-grave novel, with no obvious sign of a younger generation following - but, like Laurence Durrell in The Alexandria Quartet, or like Ford Maddox Ford in The good soldier, Gardam uses the trick of going back over essentially the same material from the viewpoint of a different central character, and showing us how it can all be read with quite a different slant. I think she must have had FMF in the back of her mind - Sir Edward Feathers sometimes seems to have more than a hint of Ashburnham (or even Tietjens) about him.

The man in the wooden hat puts Feathers's wife, Betty, in the spotlight, and shows us something about the history of the love affair hinted at in the first book, but what it's really interested in is the way two people who are married for fifty years and may be presumed to know each other better than anyone else does, can still have important pieces of their lives that they aren't prepared to share - whether or not their "secrets" are really secret. And what the presence of those "secrets" in their lives means to them.

I felt that this was perhaps even a better, more complicated novel than Old Filth, although it's difficult to assess, because it does also rest quite heavily on the heavy work of exposition and scene-setting that's already been done in the first volume. Certainly, Gardam seems to be more comfortable with Betty as a character, and is more prepared to take risks and let herself be witty.

Last friends moves the perspective to Feathers's rival, Sir Terry Veneering, and to another barrister who has played rather a minor role in the story up to now, Fiscal-Smith. It turns out that whilst everyone else is a Child of Empire, these two rather anomalously grew up in a Catherine Cookson novel. Somehow, the plunge into back-to-backs, flat caps, coal-carts and gleaning on the beach didn't feel quite right in the light of the rest of the story (although I'm sure Gardam, who grew up in the North-East in the thirties herself, is well-qualified to write about it). But the real interest of this one is not so much that additional background as the investigation into the way old age and the ticking of the clock pressures you to change the way you handle your relations with contemporaries and younger people. Resentments, secrets and passions are still there, but can you afford to let them get between you and the last few people who have any understanding of the things you have lived through?

The Man in the Wooden Hat (2009) by Jane Gardam (UK, 1928- )

Last friends (2013) by Jane Gardam (UK, 1928- )

The storyline of Old Filth doesn't seem to offer much scope for sequels - it's pretty much a cradle-to-grave novel, with no obvious sign of a younger generation following - but, like Laurence Durrell in The Alexandria Quartet, or like Ford Maddox Ford in The good soldier, Gardam uses the trick of going back over essentially the same material from the viewpoint of a different central character, and showing us how it can all be read with quite a different slant. I think she must have had FMF in the back of her mind - Sir Edward Feathers sometimes seems to have more than a hint of Ashburnham (or even Tietjens) about him.

The man in the wooden hat puts Feathers's wife, Betty, in the spotlight, and shows us something about the history of the love affair hinted at in the first book, but what it's really interested in is the way two people who are married for fifty years and may be presumed to know each other better than anyone else does, can still have important pieces of their lives that they aren't prepared to share - whether or not their "secrets" are really secret. And what the presence of those "secrets" in their lives means to them.

I felt that this was perhaps even a better, more complicated novel than Old Filth, although it's difficult to assess, because it does also rest quite heavily on the heavy work of exposition and scene-setting that's already been done in the first volume. Certainly, Gardam seems to be more comfortable with Betty as a character, and is more prepared to take risks and let herself be witty.

Last friends moves the perspective to Feathers's rival, Sir Terry Veneering, and to another barrister who has played rather a minor role in the story up to now, Fiscal-Smith. It turns out that whilst everyone else is a Child of Empire, these two rather anomalously grew up in a Catherine Cookson novel. Somehow, the plunge into back-to-backs, flat caps, coal-carts and gleaning on the beach didn't feel quite right in the light of the rest of the story (although I'm sure Gardam, who grew up in the North-East in the thirties herself, is well-qualified to write about it). But the real interest of this one is not so much that additional background as the investigation into the way old age and the ticking of the clock pressures you to change the way you handle your relations with contemporaries and younger people. Resentments, secrets and passions are still there, but can you afford to let them get between you and the last few people who have any understanding of the things you have lived through?

29thorold

A few reviews to catch up with after another little holiday in an extraordinary building, via Landmark Trust - this time we were staying in the attics of the Villa dei Vescovi, built in the 16th century as a summer residence for the Archbishops of Padua. (More info here: https://www.landmarktrust.org.uk/search-and-book/properties/villa-vescovi-vignet...

I would say something about coming back to rainy Holland, but you'll have seen on the news how much it was raining in Northern Italy when we left on Monday. Fortunately we weren't in the area directly affected by the floods, but it was very bumpy flying over the Alps.

I would say something about coming back to rainy Holland, but you'll have seen on the news how much it was raining in Northern Italy when we left on Monday. Fortunately we weren't in the area directly affected by the floods, but it was very bumpy flying over the Alps.

30thorold

Another Maigret, since I had a longish flight and a change of planes in Munich to cope with (not that I need an excuse):

Cécile est morte (1942; Maigret and the spinster/Cécile is dead) by Georges Simenon (France, 1903-1989)

Cécile has been coming to see Maigret for some time to complain about mysterious nocturnal goings-on in the apartment she shares with her elderly aunt, to the extent that she's become a standing joke with Maigret's subordinates, but so far the police haven't found any sign of wrong-doing. But then the aunt is found murdered and Cécile goes missing, only to turn up dead in a broom cupboard in the Palace of Justice. Embarrassing for the police, to say the least, but it gives Maigret an excuse to shift his attention from a tedious surveillance operation elsewhere and dig into the backgrounds of the miserly aunt and her downstairs neighbour, a shady debarred lawyer from Fontenay-le-Comte.

A fairly routine sort of Maigret, but with enough nice touches to keep the reader's attention.

Cécile est morte (1942; Maigret and the spinster/Cécile is dead) by Georges Simenon (France, 1903-1989)

Cécile has been coming to see Maigret for some time to complain about mysterious nocturnal goings-on in the apartment she shares with her elderly aunt, to the extent that she's become a standing joke with Maigret's subordinates, but so far the police haven't found any sign of wrong-doing. But then the aunt is found murdered and Cécile goes missing, only to turn up dead in a broom cupboard in the Palace of Justice. Embarrassing for the police, to say the least, but it gives Maigret an excuse to shift his attention from a tedious surveillance operation elsewhere and dig into the backgrounds of the miserly aunt and her downstairs neighbour, a shady debarred lawyer from Fontenay-le-Comte.

A fairly routine sort of Maigret, but with enough nice touches to keep the reader's attention.

31thorold

An Ali Smith novel I'd missed up to now:

Hotel world (2001) by Ali Smith (UK, 1962- )