thorold sings of May-poles, hock-carts, wassails, wakes (in Q2)

Esto es una continuación del tema thorold leant upon a coppice gate / when Frost was spectre-gray (in Q1).

CharlasClub Read 2018

Únete a LibraryThing para publicar.

Este tema está marcado actualmente como "inactivo"—el último mensaje es de hace más de 90 días. Puedes reactivarlo escribiendo una respuesta.

1thorold

I sing of brooks, of blossoms, birds, and bowers,

Of April, May, of June, and July flowers.

I sing of May-poles, hock-carts, wassails, wakes,

Of bridegrooms, brides, and of their bridal-cakes.

I write of youth, of love, and have access

By these to sing of cleanly wantonness.

I sing of dews, of rains, and piece by piece

Of balm, of oil, of spice, and ambergris.

I sing of Time's trans-shifting; and I write

How roses first came red, and lilies white.

I write of groves, of twilights, and I sing

The court of Mab, and of the fairy king.

I write of Hell; I sing (and ever shall)

Of Heaven, and hope to have it after all.

(Robert Herrick, Hesperides - "Argument")

2thorold

I'm not sure if I'm going to be covering all the topics Herrick proposes in Q2, but I'm probably in with a good chance of matching him on resistance to following a clearly-defined purpose, anyway! (And I'm going to look up "hock-cart" right after posting this...)

Major interests for Q2 are likely to be

- the RG Japan/Korea theme read, which should be fun because I start out knowing almost nothing about Japanese or Korean literature

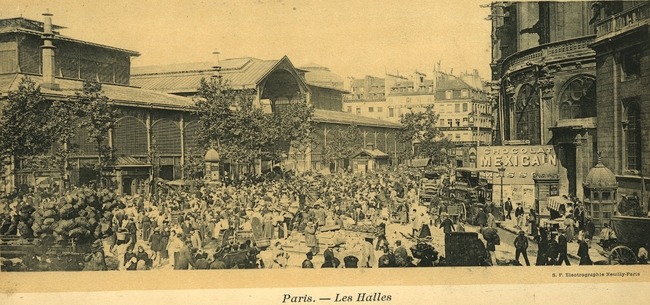

- the 19th century - I only managed one Trollope, one Hardy and two Zolas in Q1, so plenty of ground still to cover there

- crime - I started a couple of interesting new series in Q1, and I've seen some others mentioned that I would like to try out

- history - has been languishing a bit in Q1, and I'm toying with the idea of exploring the 80 years' war a bit - I've already got Geoffrey Parker's biography of Philip II sitting on the shelf.

- the TBR shelf (no, really...!)

——

OED to the rescue again - the hockay, hawkey, horkey, hookey (etc.) is a harvest-home festival in East Anglia, apparently, and the hock-cart was the specially decorated cart that brought in the last load of the harvest. Two of the four citations are from Herrick. So it’s a word that seems to belong to Q3 rather than Q2...

Major interests for Q2 are likely to be

- the RG Japan/Korea theme read, which should be fun because I start out knowing almost nothing about Japanese or Korean literature

- the 19th century - I only managed one Trollope, one Hardy and two Zolas in Q1, so plenty of ground still to cover there

- crime - I started a couple of interesting new series in Q1, and I've seen some others mentioned that I would like to try out

- history - has been languishing a bit in Q1, and I'm toying with the idea of exploring the 80 years' war a bit - I've already got Geoffrey Parker's biography of Philip II sitting on the shelf.

- the TBR shelf (no, really...!)

——

OED to the rescue again - the hockay, hawkey, horkey, hookey (etc.) is a harvest-home festival in East Anglia, apparently, and the hock-cart was the specially decorated cart that brought in the last load of the harvest. Two of the four citations are from Herrick. So it’s a word that seems to belong to Q3 rather than Q2...

3thorold

Quick summary of Q1:

51 books read in Q1:

Author gender: F 29; M 21; Other 1

By main category: Crime 4; Fiction 40; Literature 2; Poetry 3; Travel 2

By language: French 7; English 35; Dutch 2; German 3; Spanish 4

(Of the 35 English books, 8 were translations - original language Swedish 2; Danish 2; Turkish, Hungarian, Arabic and Kikerewe 1 each)

By original publication date: Earliest 1250(*); latest March 2018; mean 1965(*), median 1992. 10 books were published in the last five years; 5 were published before 1900.

(*) for consistency with what I did for the two modern editions of Wordsworth, I should probably have used the translation date 1988 for The delight of hearts instead of the presumed date of the Arabic original - in that case the earliest would be La fortune des Rougon, 1871; the mean would shift to 1979.

By format: 19 physical books; 25 read-but-not-owned (free e-books or public library); 1 audio; 6 paid e-books

Of the physical books, 10 were from the TBR (i.e. bought before the end of 2017). If I counted right, I've acquired 17 physical books in Q1, so I've reduced the TBR by 2 books (But one of those 17 is a 6-volume boxed set, so I don't really count it as a win!)

41 distinct authors read in Q1:

Author gender: F 22; M 18; Other 1

By country: UK 12; FR 6; DE 3; ARG 3; TR 2; others 15

- The gender-balance in 2017 was very skewed towards men, so I've been trying to stick to the rule of not reading two books with male authors in succession. So far that hasn't been any kind of hardship...

51 books read in Q1:

Author gender: F 29; M 21; Other 1

By main category: Crime 4; Fiction 40; Literature 2; Poetry 3; Travel 2

By language: French 7; English 35; Dutch 2; German 3; Spanish 4

(Of the 35 English books, 8 were translations - original language Swedish 2; Danish 2; Turkish, Hungarian, Arabic and Kikerewe 1 each)

By original publication date: Earliest 1250(*); latest March 2018; mean 1965(*), median 1992. 10 books were published in the last five years; 5 were published before 1900.

(*) for consistency with what I did for the two modern editions of Wordsworth, I should probably have used the translation date 1988 for The delight of hearts instead of the presumed date of the Arabic original - in that case the earliest would be La fortune des Rougon, 1871; the mean would shift to 1979.

By format: 19 physical books; 25 read-but-not-owned (free e-books or public library); 1 audio; 6 paid e-books

Of the physical books, 10 were from the TBR (i.e. bought before the end of 2017). If I counted right, I've acquired 17 physical books in Q1, so I've reduced the TBR by 2 books (But one of those 17 is a 6-volume boxed set, so I don't really count it as a win!)

41 distinct authors read in Q1:

Author gender: F 22; M 18; Other 1

By country: UK 12; FR 6; DE 3; ARG 3; TR 2; others 15

- The gender-balance in 2017 was very skewed towards men, so I've been trying to stick to the rule of not reading two books with male authors in succession. So far that hasn't been any kind of hardship...

5thorold

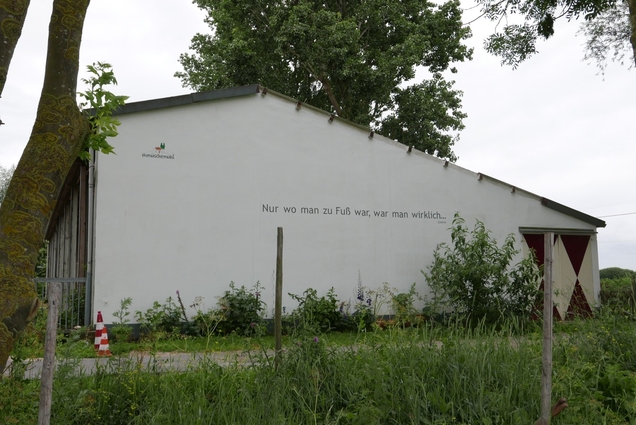

Spring seems to be getting going at last here, even if it's a bit of a struggle (yesterday I had to seek cover from a hail shower on the beach...). Anyway, it's probably fitting to mark the start of Q2 with a book that celebrates the Great Outdoors - or at least as Great as the Great Outdoors ever can be in a really small country.

De eerste wandelaar: in de voetsporen van een wandelende dominee (2017) by Flip van Doorn (Netherlands, 1967- )

Flip van Doorn writes walking columns for a couple of Dutch newspapers and is the author of several walking and cycling guides. He lives at IJlst in Friesland.

Between 1874 and 1888 Jacobus Craandijk (1834-1912), the minister of the Mennonite (Doopsgezinde) community in Rotterdam and later in Haarlem, published eight volumes of his Wanderings through the Netherlands with pen and pencil (Wandelingen door Nederland met pen en potlood). His books, originally issued as grand coffee-table editions illustrated by a well-known landscape artist, but later repackaged as pocket-sized guidebooks, were a big success, not only introducing the rapidly-growing Dutch middle-classes to the pleasures of exploring their own country on foot but also helping to build support for the creation of movements to preserve historic buildings and landscapes.

Flip van Doorn obviously feels a great affinity for Craandijk, with whom he not only has an occupation in common, but also a little bit of DNA - as he accidentally discovered whilst researching his family tree, his grandmother was a great-niece of Craandijk's. But more to the point, Craandijk was the pioneer - or at least first great populariser, which is what "pioneer" and "inventor" usually mean in practice - of wandering (rambling) as a pleasure in itself. He is not especially interested in covering distance or getting to a destination. Walking for him is all about what you experience on the way - discovering beauty in the landscape, understanding its history and ecology, lying on your back in the moss and looking up at the clouds, and so on. The walks Craandijk describes don't come with turn-by-turn instructions or a line on the map - it is all about following your nose and discovering stuff for yourself. And that's almost as radical a concept for us to take in nowadays as it was for Craandijk's early readers. We're so used to following coloured markers, leaflets, GPS routes and the rest and of having other people do the decision-making for us that it's almost scary to go out with nothing more than a general sense of what you want to see and where you can home from afterwards. But it can be very rewarding - I took a day in the middle of reading this book to wander, Craandijk-style, between Vorden and Zutphen, an area I hardly know at all. Very pleasant (the photo in >1 thorold: is from that walk).

This isn't a biography or a condensed version of the Wandelingen - Van Doorn writes about Craandijk's background and career as a clergyman, writer and antiquary, about the process of writing and publication (crowd-sourcing and advertorial are clearly nothing new in the publishing world...), about the Netherlands as they were in the 1870s and as they are now, about Mennonites, about some of the places that interested Craandijk and how they are experienced by a modern walker, about preserving ancient buildings and re-establishing damaged landscapes ("re-meandering" is a big deal nowadays - and something I came across on the river Berkel on my "Craandijk walk"). It's a gloriously random and jumbled account of the experience of discovering and thinking about Craandijk - a mosaic, van Doorn calls it - with a lovely, frank listing in the last chapter of the bits and pieces that were left over unused at the end of the exercise. Re-meandering, indeed.

In some ways the 1870s were an ideal moment for Dutch walkers - for the first time, you could reach just about any point in the Netherlands quickly and in comfort by train, steam-tram or steamboat, but there were no bicycles or motor-cars to spoil things. But in other ways we have it so much better now - beautiful topographic maps on your phone (and all eight volumes of Craandijk as well if you want!), hundreds of former private parks are open to walkers, there are thousands of kilometres of marked circular walks, long-distance trails, node-point-routes, etc., there are information boards to explain anything rare or historic so that we don't overlook it, etc. And wherever you look there is someone busy re-meandering. But still, if we happen to end up on the wrong side of a Friesian canal nowadays, I wouldn't fancy our chances of finding a milkmaid to row us across...

Not a book many CR members will have a use for, but highly-recommended for anyone who reads Dutch and enjoys walking with their eyes and ears open.

---

Flip van Doorn's blog: http://www.flipvandoorn.nl/website/

Craandijk site, with links to the Wandelingen on the DBNL: http://www.jacobuscraandijk.nl/wandelingen-1874-1888/

De eerste wandelaar: in de voetsporen van een wandelende dominee (2017) by Flip van Doorn (Netherlands, 1967- )

Flip van Doorn writes walking columns for a couple of Dutch newspapers and is the author of several walking and cycling guides. He lives at IJlst in Friesland.

Between 1874 and 1888 Jacobus Craandijk (1834-1912), the minister of the Mennonite (Doopsgezinde) community in Rotterdam and later in Haarlem, published eight volumes of his Wanderings through the Netherlands with pen and pencil (Wandelingen door Nederland met pen en potlood). His books, originally issued as grand coffee-table editions illustrated by a well-known landscape artist, but later repackaged as pocket-sized guidebooks, were a big success, not only introducing the rapidly-growing Dutch middle-classes to the pleasures of exploring their own country on foot but also helping to build support for the creation of movements to preserve historic buildings and landscapes.

Flip van Doorn obviously feels a great affinity for Craandijk, with whom he not only has an occupation in common, but also a little bit of DNA - as he accidentally discovered whilst researching his family tree, his grandmother was a great-niece of Craandijk's. But more to the point, Craandijk was the pioneer - or at least first great populariser, which is what "pioneer" and "inventor" usually mean in practice - of wandering (rambling) as a pleasure in itself. He is not especially interested in covering distance or getting to a destination. Walking for him is all about what you experience on the way - discovering beauty in the landscape, understanding its history and ecology, lying on your back in the moss and looking up at the clouds, and so on. The walks Craandijk describes don't come with turn-by-turn instructions or a line on the map - it is all about following your nose and discovering stuff for yourself. And that's almost as radical a concept for us to take in nowadays as it was for Craandijk's early readers. We're so used to following coloured markers, leaflets, GPS routes and the rest and of having other people do the decision-making for us that it's almost scary to go out with nothing more than a general sense of what you want to see and where you can home from afterwards. But it can be very rewarding - I took a day in the middle of reading this book to wander, Craandijk-style, between Vorden and Zutphen, an area I hardly know at all. Very pleasant (the photo in >1 thorold: is from that walk).

This isn't a biography or a condensed version of the Wandelingen - Van Doorn writes about Craandijk's background and career as a clergyman, writer and antiquary, about the process of writing and publication (crowd-sourcing and advertorial are clearly nothing new in the publishing world...), about the Netherlands as they were in the 1870s and as they are now, about Mennonites, about some of the places that interested Craandijk and how they are experienced by a modern walker, about preserving ancient buildings and re-establishing damaged landscapes ("re-meandering" is a big deal nowadays - and something I came across on the river Berkel on my "Craandijk walk"). It's a gloriously random and jumbled account of the experience of discovering and thinking about Craandijk - a mosaic, van Doorn calls it - with a lovely, frank listing in the last chapter of the bits and pieces that were left over unused at the end of the exercise. Re-meandering, indeed.

In some ways the 1870s were an ideal moment for Dutch walkers - for the first time, you could reach just about any point in the Netherlands quickly and in comfort by train, steam-tram or steamboat, but there were no bicycles or motor-cars to spoil things. But in other ways we have it so much better now - beautiful topographic maps on your phone (and all eight volumes of Craandijk as well if you want!), hundreds of former private parks are open to walkers, there are thousands of kilometres of marked circular walks, long-distance trails, node-point-routes, etc., there are information boards to explain anything rare or historic so that we don't overlook it, etc. And wherever you look there is someone busy re-meandering. But still, if we happen to end up on the wrong side of a Friesian canal nowadays, I wouldn't fancy our chances of finding a milkmaid to row us across...

Not a book many CR members will have a use for, but highly-recommended for anyone who reads Dutch and enjoys walking with their eyes and ears open.

---

Flip van Doorn's blog: http://www.flipvandoorn.nl/website/

Craandijk site, with links to the Wandelingen on the DBNL: http://www.jacobuscraandijk.nl/wandelingen-1874-1888/

6baswood

I should think that many countries have walkers like Flip Van Doorn who publish books of their walks; the modern walkers usually in the footsteps of walking hero's from the past. England has quite a few. When I lived in London it used to take me an hour and a half on the train to get to a starting point for country walking and you needed walking guides to avoid all the barbed wire surrounding the farm land. It was easier when I lived in Derbyshire in the peak National Park where there is plenty of wild moorland for walking, however it is so popular that you are forever tripping over other people. Last year when recovering from an operation my local Doctor prescribed walking and I took myself off for days at a time literally walking from my front door, because here in rural France there is woodland and farmland, hills aplenty and no restrictions as to where you can walk. Great walking country where there are no other walkers, and I thought of making maps of where I walked, but in the end thought it best just to store all the knowledge in my head.

7thorold

>6 baswood: England has quite a few

I seem to remember coming across something about a guy called Wordsworth, not all that long ago... :-)

And plenty of other famous examples, as you say. If there is something distinctively Dutch about Craandijk then it’s probably that it still came across as new and exciting as late as the 1870s - in England, Germany, the US, people had been romantically walking since the beginning of the century at least.

The Netherlands is still a slightly complicated place to walk in because you can’t tell directly from maps what places you have access to. Most public and private landowners give access to walkers (amongst other things, there’s a tax incentive to do so), but some don’t. And unless you’ve been there before or are following an official route of some sort, you can’t be sure until you’ve read the notice at the gate. There are still a few places where you have to buy a ticket or join a club to get in, as well...

There does seem to be a growing literature about people who write about walking - Rebecca Solnit, Geoff Nicholson, Frédéric Gros, and plenty of others have written that kind of book lately.

I seem to remember coming across something about a guy called Wordsworth, not all that long ago... :-)

And plenty of other famous examples, as you say. If there is something distinctively Dutch about Craandijk then it’s probably that it still came across as new and exciting as late as the 1870s - in England, Germany, the US, people had been romantically walking since the beginning of the century at least.

The Netherlands is still a slightly complicated place to walk in because you can’t tell directly from maps what places you have access to. Most public and private landowners give access to walkers (amongst other things, there’s a tax incentive to do so), but some don’t. And unless you’ve been there before or are following an official route of some sort, you can’t be sure until you’ve read the notice at the gate. There are still a few places where you have to buy a ticket or join a club to get in, as well...

There does seem to be a growing literature about people who write about walking - Rebecca Solnit, Geoff Nicholson, Frédéric Gros, and plenty of others have written that kind of book lately.

8AlisonY

Sigh - I love the Netherlands. We went back for a family holiday last year, and had the kids not been with us I would have enjoyed taking myself off on many a long meander into the countryside.

Having said that, we all enjoyed a stroll around part of Loonse en Drunense Duinen. A bizarrely unexpected yet wonderful place.

Having said that, we all enjoyed a stroll around part of Loonse en Drunense Duinen. A bizarrely unexpected yet wonderful place.

9thorold

>8 AlisonY: Loonse en Drunense Duinen - fun! there's somewhere I haven't been for years. It used to be a pain to get there, but it looks as though there is now a much better bus service around there - I should put it on my list again. As long as it doesn't involve going anywhere near the Efteling.

Craandijk never seems to have gone to the Loonse en Drunense Duinen at all - he wasn't a fan of "woeste natuur" and tended to stay away from sands and heaths as far as possible.

I was walking in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen yesterday, and had time to read most of another crime story on the train. This is the third in the Canadian series I started with a few weeks ago, and of course very seasonal:

The cruellest month (2007) by Louise Penny (Canada, 1958- )

The residents of Three Pines seem to have got used to their peaceful village filling up with police officers and crime-scene tape by now: no-one really bothers to act surprised when it turns out that the sudden death that marred their Easter celebrations was the result of foul play. When Chief-Inspector Gamache and his team roll into town once again, the villagers are simply pleased to see their old friends again and have a new source of gossip...

Silly as the premise is, Penny manages to build it into a psychologically interesting plot, where it turns out that a person universally described as popular and well-liked actually had a whole slew of people with plausible motives for doing away with her. And of course Gamache is still confronted with nasty internal conflicts in the Sûreté as the echoes of the Arnot case rumble on interminably - as with everyone's favourite crime-scene, the Old Hadley Place, Penny is clearly too frugal to expend all the possibilities of this useful bit of plot in a single book.

Happily we don't get anything like as many T.S. Eliot references as I was fearing - after an initial flurry, Penny manages to restrain herself quite well. But she does come up with a second Local Poet to give herself the freedom to insert some really bad fragments of original verse into the story...

Craandijk never seems to have gone to the Loonse en Drunense Duinen at all - he wasn't a fan of "woeste natuur" and tended to stay away from sands and heaths as far as possible.

I was walking in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen yesterday, and had time to read most of another crime story on the train. This is the third in the Canadian series I started with a few weeks ago, and of course very seasonal:

The cruellest month (2007) by Louise Penny (Canada, 1958- )

The residents of Three Pines seem to have got used to their peaceful village filling up with police officers and crime-scene tape by now: no-one really bothers to act surprised when it turns out that the sudden death that marred their Easter celebrations was the result of foul play. When Chief-Inspector Gamache and his team roll into town once again, the villagers are simply pleased to see their old friends again and have a new source of gossip...

Silly as the premise is, Penny manages to build it into a psychologically interesting plot, where it turns out that a person universally described as popular and well-liked actually had a whole slew of people with plausible motives for doing away with her. And of course Gamache is still confronted with nasty internal conflicts in the Sûreté as the echoes of the Arnot case rumble on interminably - as with everyone's favourite crime-scene, the Old Hadley Place, Penny is clearly too frugal to expend all the possibilities of this useful bit of plot in a single book.

Happily we don't get anything like as many T.S. Eliot references as I was fearing - after an initial flurry, Penny manages to restrain herself quite well. But she does come up with a second Local Poet to give herself the freedom to insert some really bad fragments of original verse into the story...

10thorold

Just noticed that according to my profile page, I'm "Currently reading":

I don't think I've touched any of those in six months. Maybe I should add those to the reading aims in >2 thorold: above!

Malena es un nombre de tango by Almudena Grandes

Illusions perdues by Honoré de Balzac

Meneer Beerta by J.J. Voskuil

Quer pasticciaccio brutto de via Merulana by Carlo Emilio Gadda

Así empieza lo malo by Javier Marías

I don't think I've touched any of those in six months. Maybe I should add those to the reading aims in >2 thorold: above!

11thorold

...and my first read for the Japan/Korea thread:

Kokoro (1914; new English translation 2010) by Natsume Sōseki (Japan, 1867-1916), translated by Meredith McKinney (Australia)

Sōseki is often cited as the most distinguished modern Japanese novelist. He studied English at Tokyo Imperial University and was one of the first Japanese to get the chance to study abroad, spending two years ("the most unpleasant years in my life") at UCL. After his return, he taught literature at Tokyo University. He first came to prominence as a writer with I am a cat in 1905.

Meredith McKinney teaches at the Australian National University and translates medieval and modern Japanese literature (she's also the daughter of the well-known Australian poet Judith Wright).

I have a feeling that Kokoro is a book that will make more and more sense the more I know about modern Japanese culture. On one level it's a simple story about friendship and betrayal, but on another level it's a working-out of the cultural tensions set up in the minds of Japanese intellectuals who lived through the opening-up of Japan to western ideas during the Meiji period (Sōseki was born in the year of Meiji's accession to the imperial throne). The foreground story of Kokoro takes place in the months around the emperor's death, and its main character, Sensei (teacher), is an older man - a contemporary of the author - whose life has been messed up by his inability to resolve the existential conflict between the demands of the two threads of his upbringing, the requirement to subsume himself into the traditional, collective family values of middle-class Japanese society setting itself against the western need for intellectual self-determination. The narrator of the first part of the book is a man of a younger generation who gets into a similar ethical tangle, but with different dimensions and results.

It's all very carefully, delicately built up, with a lot of everyday detail about the rapidly-changing face of Japan in the decades before 1914 used to reflect and explain the development of the conflicts the characters are dealing with. Very much a book about male friendships (what used to be called "homosocial" relationships in the good old days of literary theory), where the women rarely speak and don't have all that much to do apart from arranging flowers and cooking (is that why Penguin coincidentally put a brush-stroke across the woman's eyes in the cover design?). But that's an accusation that would be equally true of a lot of western novels of the same period.

Very interesting, and McKinnon's translation reads very naturally and transparently.

Kokoro (1914; new English translation 2010) by Natsume Sōseki (Japan, 1867-1916), translated by Meredith McKinney (Australia)

Sōseki is often cited as the most distinguished modern Japanese novelist. He studied English at Tokyo Imperial University and was one of the first Japanese to get the chance to study abroad, spending two years ("the most unpleasant years in my life") at UCL. After his return, he taught literature at Tokyo University. He first came to prominence as a writer with I am a cat in 1905.

Meredith McKinney teaches at the Australian National University and translates medieval and modern Japanese literature (she's also the daughter of the well-known Australian poet Judith Wright).

I have a feeling that Kokoro is a book that will make more and more sense the more I know about modern Japanese culture. On one level it's a simple story about friendship and betrayal, but on another level it's a working-out of the cultural tensions set up in the minds of Japanese intellectuals who lived through the opening-up of Japan to western ideas during the Meiji period (Sōseki was born in the year of Meiji's accession to the imperial throne). The foreground story of Kokoro takes place in the months around the emperor's death, and its main character, Sensei (teacher), is an older man - a contemporary of the author - whose life has been messed up by his inability to resolve the existential conflict between the demands of the two threads of his upbringing, the requirement to subsume himself into the traditional, collective family values of middle-class Japanese society setting itself against the western need for intellectual self-determination. The narrator of the first part of the book is a man of a younger generation who gets into a similar ethical tangle, but with different dimensions and results.

It's all very carefully, delicately built up, with a lot of everyday detail about the rapidly-changing face of Japan in the decades before 1914 used to reflect and explain the development of the conflicts the characters are dealing with. Very much a book about male friendships (what used to be called "homosocial" relationships in the good old days of literary theory), where the women rarely speak and don't have all that much to do apart from arranging flowers and cooking (is that why Penguin coincidentally put a brush-stroke across the woman's eyes in the cover design?). But that's an accusation that would be equally true of a lot of western novels of the same period.

Very interesting, and McKinnon's translation reads very naturally and transparently.

12baswood

I read Kokoro three years ago and loved it. I read the original translation by Edwin Mclellan, which seemed to read well enough. Our old friend rebeccanyc leads the way with the reviews.

13thorold

Time for a bit of lightish background reading on modern Japan:

Inventing Japan, 1853-1964 (2003) by Ian Buruma (Netherlands, UK, etc., 1951- )

Ian Buruma is very well-known as a historian, journalist and essayist, and was recently appointed editor of the NYRB. He's written many books on the Far East, international relations, religion, politics, 20th century history, etc., etc. He grew up in the Netherlands with a British mother (John Schlesinger's sister!) and a Dutch father. He studied history and Chinese literature in Leiden and Japanese cinema in Tokyo, and has lived for lengthy periods in Japan and Hong Kong. Wikipedia tells me that Buruma's grandfather was a well-known Mennonite minister, which even gives me a tenuous link with Craandijk - see >5 thorold: above.

Inventing Japan is one of the Modern Library Chronicles series of brief histories, taking us through the history of modern Japan from Commodore Perry to the Tokyo Olympics in not much more than 150 pages, but it's far from being a mere gallop through the facts. As you might expect from Buruma, the stress is on understanding the development of Japanese political thought and exploring how that led to the peculiarities of the Japanese kokutai (polity) as it leapt from feudalism to Meiji authoritarianism, Showa militarism, and the postwar LDP machine. And of course, he's not slow to express his opinion of what went wrong with all these different visions of Japaneseness. Buruma looks not only at the roles played by political and military figures, but also at the cultural background to the main currents of Japanese thought during the period - novelists, film-makers, popular journalism, propaganda, etc.

One thing that struck me from Buruma's account was the extent to which Japanese scholars were already aware of (and using) western ideas during the Dutch period - the idea of Japan suddenly being made to open the shutters and discover the modern world for the first time in the 1850s makes a good story, but of course it couldn't really have been quite as sudden as that in real life. Another was the way that the state reacted to the destabilising effects of outside ideas by inventing new "ancient traditions" to reinforce the links between authority, religion and nationalism - not so very different to what was happening in Britain during the industrial revolution or is happening now in many postcolonial states.

Obviously, there has to be a lot of important material that gets missed out or skipped over lightly in a book this size (quite apart from the fact that the book was written 15 years ago and only takes the main story up to 1964 anyway). Buruma is an opinionated writer, albeit one I usually find myself agreeing with, so it's probably best not to take this book in isolation, but it is a good way to get the broad outlines of the story fixed in your mind. It looks like a useful jumping-off point, and it comes with a comprehensive bibliography to facilitate that kind of use.

Inventing Japan, 1853-1964 (2003) by Ian Buruma (Netherlands, UK, etc., 1951- )

Ian Buruma is very well-known as a historian, journalist and essayist, and was recently appointed editor of the NYRB. He's written many books on the Far East, international relations, religion, politics, 20th century history, etc., etc. He grew up in the Netherlands with a British mother (John Schlesinger's sister!) and a Dutch father. He studied history and Chinese literature in Leiden and Japanese cinema in Tokyo, and has lived for lengthy periods in Japan and Hong Kong. Wikipedia tells me that Buruma's grandfather was a well-known Mennonite minister, which even gives me a tenuous link with Craandijk - see >5 thorold: above.

Inventing Japan is one of the Modern Library Chronicles series of brief histories, taking us through the history of modern Japan from Commodore Perry to the Tokyo Olympics in not much more than 150 pages, but it's far from being a mere gallop through the facts. As you might expect from Buruma, the stress is on understanding the development of Japanese political thought and exploring how that led to the peculiarities of the Japanese kokutai (polity) as it leapt from feudalism to Meiji authoritarianism, Showa militarism, and the postwar LDP machine. And of course, he's not slow to express his opinion of what went wrong with all these different visions of Japaneseness. Buruma looks not only at the roles played by political and military figures, but also at the cultural background to the main currents of Japanese thought during the period - novelists, film-makers, popular journalism, propaganda, etc.

One thing that struck me from Buruma's account was the extent to which Japanese scholars were already aware of (and using) western ideas during the Dutch period - the idea of Japan suddenly being made to open the shutters and discover the modern world for the first time in the 1850s makes a good story, but of course it couldn't really have been quite as sudden as that in real life. Another was the way that the state reacted to the destabilising effects of outside ideas by inventing new "ancient traditions" to reinforce the links between authority, religion and nationalism - not so very different to what was happening in Britain during the industrial revolution or is happening now in many postcolonial states.

Obviously, there has to be a lot of important material that gets missed out or skipped over lightly in a book this size (quite apart from the fact that the book was written 15 years ago and only takes the main story up to 1964 anyway). Buruma is an opinionated writer, albeit one I usually find myself agreeing with, so it's probably best not to take this book in isolation, but it is a good way to get the broad outlines of the story fixed in your mind. It looks like a useful jumping-off point, and it comes with a comprehensive bibliography to facilitate that kind of use.

14janeajones

Inventing Japan sounds very informative.

15thorold

Another sensei-novel, but one that doesn't take itself all that seriously...

Strange weather in Tokyo (2001; English 2012) by Hiromi Kawakami (Japan, 1958- ), translated by Allison Markin Powell (USA)

(original English title: The briefcase)

Tsukiko, a Tokyo office-worker in her late thirties, is drawn into conversation by the elderly man drinking sake next to her in a neighbourhood bar - it turns out that he's her former high-school Japanese literature teacher. The two of them don't seem to have much in common - they're thirty years apart in age, and Tsukiko was never a good student and still has a deaf ear for classical poetry. She addresses her old teacher as "Sensei" not so much out of respect but rather because she can't remember his name at first. But they somehow drift into being companionable drinking acquaintances, then friends, then (after many quarrels about unimportant things) discover that they really need each other's company.

This is a very engaging, delicate-but-funny (occasionally even surrealistic) May-to-December romance and a commentary on modern urban loneliness, but I think Kawakami is also enjoying herself pulling the reader's leg a bit - while Tsukiko is to all appearances a classic western chick-lit character, the detail of the story is obsessively Japanese to the point of self-parody - the over-specified food, the discussions about the correct way to pour sake, the activities Tsokiko and Sensei share (mushroom-hunting, a calligraphy exhibition, a vegetable market, a hot-springs inn, a pachinko parlour, a passionate night of octopus-related haiku-composition...). And then there's the odd figure of Sensei's presumably-dead wife, as subversively odd as Sensei is conservatively old-fashioned. There's definitely a bit more going on here than an unlikely love-affair!

Strange weather in Tokyo (2001; English 2012) by Hiromi Kawakami (Japan, 1958- ), translated by Allison Markin Powell (USA)

(original English title: The briefcase)

Tsukiko, a Tokyo office-worker in her late thirties, is drawn into conversation by the elderly man drinking sake next to her in a neighbourhood bar - it turns out that he's her former high-school Japanese literature teacher. The two of them don't seem to have much in common - they're thirty years apart in age, and Tsukiko was never a good student and still has a deaf ear for classical poetry. She addresses her old teacher as "Sensei" not so much out of respect but rather because she can't remember his name at first. But they somehow drift into being companionable drinking acquaintances, then friends, then (after many quarrels about unimportant things) discover that they really need each other's company.

This is a very engaging, delicate-but-funny (occasionally even surrealistic) May-to-December romance and a commentary on modern urban loneliness, but I think Kawakami is also enjoying herself pulling the reader's leg a bit - while Tsukiko is to all appearances a classic western chick-lit character, the detail of the story is obsessively Japanese to the point of self-parody - the over-specified food, the discussions about the correct way to pour sake, the activities Tsokiko and Sensei share (mushroom-hunting, a calligraphy exhibition, a vegetable market, a hot-springs inn, a pachinko parlour, a passionate night of octopus-related haiku-composition...). And then there's the odd figure of Sensei's presumably-dead wife, as subversively odd as Sensei is conservatively old-fashioned. There's definitely a bit more going on here than an unlikely love-affair!

16janeajones

15> I'm intrigued.

17thorold

Still catching up in a brief gap between two lots of visitors. You could call this another Sensei story, although in this case the Sensei-pupil relationship was not in the book but was instrumental in getting it published...

The silver spoon : memoir of a boyhood in Japan (serial 1913-15, book 1922, English 2015) by Kansuke Naka (Japan, 1885-1965), translated by Hiroaki Sato (Japan, USA, 1948-), illustrated by Sumiko Yano

![]()

Hiroaki Sato is a distinguished Japanese poet and translator. He's lived mainly in the US since the 1960s and has taught at various American universities.

Kansuke Naka was a student of Natsume Sōseki, and it was Sōseki's influence and support that led to Naka's childhood memoir first being published as a serial in Asahi Shinbun in 1913 (part I) and 1915 (part II). Publication in book form followed in 1922, after Sōseki's death, and from the 1930s on the memoir gradually became established as a Japanese favourite. Sato tells us in his introduction that it reached a cumulative total of a million sales in Japan in 2006. Reading between the lines, it looks as though Sato must be at least partly to blame for the long delay before the appearance of an English translation - he started working on it in the late sixties and first published some excerpts from the work-in-progress in 1972...

Naka writes about his childhood in Meiji-era suburban Tokyo (the 1880s and 90s). His father belonged to the "gentry" class, but was not especially well off - he started off as an estate administrator, and under the new régime went into business with his former feudal lord. Young Kansuke was a sickly child (as he tells us every other page or so, throughout the book), and was obviously rather too much fussed-over by the aunt who acted as his nanny. But he describes very charmingly the life of those times, when popular culture was still struggling to assimilate the changes being imposed on it. There's a lot about Buddhist festivals, fairs, entertainments, street-life, school, and about the normal preoccupations of childhood - toys, games, friends and playmates, etc.

A lot of the emphasis of the book seems to be Naka's desire to undermine the idea that Japaneseness necessarily revolves around nationalism and militarism - we have to laugh at wimpy little Kansuke re-enacting the 16th century sword fights from his story books in desperate hand-to-hand combat with his elderly aunt, and everyone in the book who embodies any kind of macho martial spirit - school bullies, a jingoistic teacher, Kansuke's big brother - is made to seem foolish. Flowers, insects, Buddhism, painting and poetry are clearly much more important. Sumiko Yano's drawings of cute little figures in kimonos flying kites almost manage to push this over into kitsch, but the genuine feeling and modesty of Naka's writing just about manages to save it.

The silver spoon : memoir of a boyhood in Japan (serial 1913-15, book 1922, English 2015) by Kansuke Naka (Japan, 1885-1965), translated by Hiroaki Sato (Japan, USA, 1948-), illustrated by Sumiko Yano

Hiroaki Sato is a distinguished Japanese poet and translator. He's lived mainly in the US since the 1960s and has taught at various American universities.

Kansuke Naka was a student of Natsume Sōseki, and it was Sōseki's influence and support that led to Naka's childhood memoir first being published as a serial in Asahi Shinbun in 1913 (part I) and 1915 (part II). Publication in book form followed in 1922, after Sōseki's death, and from the 1930s on the memoir gradually became established as a Japanese favourite. Sato tells us in his introduction that it reached a cumulative total of a million sales in Japan in 2006. Reading between the lines, it looks as though Sato must be at least partly to blame for the long delay before the appearance of an English translation - he started working on it in the late sixties and first published some excerpts from the work-in-progress in 1972...

Naka writes about his childhood in Meiji-era suburban Tokyo (the 1880s and 90s). His father belonged to the "gentry" class, but was not especially well off - he started off as an estate administrator, and under the new régime went into business with his former feudal lord. Young Kansuke was a sickly child (as he tells us every other page or so, throughout the book), and was obviously rather too much fussed-over by the aunt who acted as his nanny. But he describes very charmingly the life of those times, when popular culture was still struggling to assimilate the changes being imposed on it. There's a lot about Buddhist festivals, fairs, entertainments, street-life, school, and about the normal preoccupations of childhood - toys, games, friends and playmates, etc.

A lot of the emphasis of the book seems to be Naka's desire to undermine the idea that Japaneseness necessarily revolves around nationalism and militarism - we have to laugh at wimpy little Kansuke re-enacting the 16th century sword fights from his story books in desperate hand-to-hand combat with his elderly aunt, and everyone in the book who embodies any kind of macho martial spirit - school bullies, a jingoistic teacher, Kansuke's big brother - is made to seem foolish. Flowers, insects, Buddhism, painting and poetry are clearly much more important. Sumiko Yano's drawings of cute little figures in kimonos flying kites almost manage to push this over into kitsch, but the genuine feeling and modesty of Naka's writing just about manages to save it.

18thorold

A Mishima I hadn't read that I spotted in the library:

After the banquet (1960, English 1963) by Yukio Mishima (Japan, 1925-1970), translated by Donald Keene (US, Japan, 1922-)

Mishima was of course the Japanese writer best known outside Japan before Murakami came along, far eclipsing the two Nobel laureates. I've taken a lot of pleasure from those of his books that I've read so far (Forbidden colours, Confessions of a mask, The sailor who fell from grace with the sea), but I'm a little queasy about enjoying the work of a writer who dedicated himself to martial arts and ended his career in a futile attempt at a right-wing coup directly after putting the finishing touch to his magnum opus. I think I need to read more about him before getting into that discussion, though...

Donald Keene is a noted Japanese scholar and an emeritus professor at Columbia, where he taught for 50 years. He moved to Japan and took on Japanese citizenship in 2011.

After the banquet (1960) falls about a third of the way through Mishima's impressively-long list of books - the fact that it appeared in English only a couple of years after its original Japanese publication is an indication of Mishima's reputation at the time. It's basically a political satire in form: a self-made businesswoman marries a gentlemanly, old-style politician and engages herself on his behalf in an election campaign full of dirty tricks on both sides. Mishima evidently made it a little too realistic, as the former foreign minister Hachiro Arita (who had just fought an election in rather similar circumstances) successfully sued him for invasion of privacy.

It feels rather old-fashioned as a novel, because of the way Mishima keeps his distance from both the main characters, showing us what they are thinking and feeling indirectly and mostly through externals - clothes, physical settings, food, weather. We aren't allowed to sympathise too closely either with Kazu's frenetic need to drive events or with Noguchi's self-deceiving ethical stance, but we do get to see how they fail to communicate with each other almost from the beginning of the story. We do very clearly see Mishima's absolute contempt for the way Japan's post-war political machine operated in an environment free of any sort of ideological commitment, driven only by self-interest, cronyism and hard cash. He doesn't really need to spell out where they learnt that from, but there are a couple of significant passing mentions of US military bases. Probably the closest we come to a genuine emotion in the book is in Kazu's (doomed) desire to anchor her anomalous life within the norms of Japanese society, as symbolised by her aspiration to be buried in Noguchi's family tomb.

Probably not a major work, but interesting, anyway.

After the banquet (1960, English 1963) by Yukio Mishima (Japan, 1925-1970), translated by Donald Keene (US, Japan, 1922-)

Mishima was of course the Japanese writer best known outside Japan before Murakami came along, far eclipsing the two Nobel laureates. I've taken a lot of pleasure from those of his books that I've read so far (Forbidden colours, Confessions of a mask, The sailor who fell from grace with the sea), but I'm a little queasy about enjoying the work of a writer who dedicated himself to martial arts and ended his career in a futile attempt at a right-wing coup directly after putting the finishing touch to his magnum opus. I think I need to read more about him before getting into that discussion, though...

Donald Keene is a noted Japanese scholar and an emeritus professor at Columbia, where he taught for 50 years. He moved to Japan and took on Japanese citizenship in 2011.

After the banquet (1960) falls about a third of the way through Mishima's impressively-long list of books - the fact that it appeared in English only a couple of years after its original Japanese publication is an indication of Mishima's reputation at the time. It's basically a political satire in form: a self-made businesswoman marries a gentlemanly, old-style politician and engages herself on his behalf in an election campaign full of dirty tricks on both sides. Mishima evidently made it a little too realistic, as the former foreign minister Hachiro Arita (who had just fought an election in rather similar circumstances) successfully sued him for invasion of privacy.

It feels rather old-fashioned as a novel, because of the way Mishima keeps his distance from both the main characters, showing us what they are thinking and feeling indirectly and mostly through externals - clothes, physical settings, food, weather. We aren't allowed to sympathise too closely either with Kazu's frenetic need to drive events or with Noguchi's self-deceiving ethical stance, but we do get to see how they fail to communicate with each other almost from the beginning of the story. We do very clearly see Mishima's absolute contempt for the way Japan's post-war political machine operated in an environment free of any sort of ideological commitment, driven only by self-interest, cronyism and hard cash. He doesn't really need to spell out where they learnt that from, but there are a couple of significant passing mentions of US military bases. Probably the closest we come to a genuine emotion in the book is in Kazu's (doomed) desire to anchor her anomalous life within the norms of Japanese society, as symbolised by her aspiration to be buried in Noguchi's family tomb.

Probably not a major work, but interesting, anyway.

19thorold

Spark notes, part 97 (or so). Despite the vaguely Japanese-looking cover image (by John Alcorn), this has nothing to do with the Korea/Japan theme...

Territorial rights (1979) by Muriel Spark (UK, 1918-2006)

Perhaps because of the Venetian setting, this glorious romp of a crime novel that refuses to take itself seriously sometimes feels as though Spark is sending up Patricia Highsmith. There is a beautiful, over-inquisitive boy (escaped from The Comforters via Death in Venice), a Ripleyesque, amoral American millionaire, and a set of supremely prosaic English adulterers (a retired headmaster and his former Domestic Science teacher), all mixed up with a ludicrous Bulgarian spy plot, Italian gangsters and a dodgy detective agency that specialises in blackmailing its clients. And the headmaster's offstage wife who is forever nodding off to sleep over viciously-parodied excerpts from a sixties kitchen-sink novel. Far too much going on, not much chance of identifying any deeper meaning, but great fun.

Territorial rights (1979) by Muriel Spark (UK, 1918-2006)

Perhaps because of the Venetian setting, this glorious romp of a crime novel that refuses to take itself seriously sometimes feels as though Spark is sending up Patricia Highsmith. There is a beautiful, over-inquisitive boy (escaped from The Comforters via Death in Venice), a Ripleyesque, amoral American millionaire, and a set of supremely prosaic English adulterers (a retired headmaster and his former Domestic Science teacher), all mixed up with a ludicrous Bulgarian spy plot, Italian gangsters and a dodgy detective agency that specialises in blackmailing its clients. And the headmaster's offstage wife who is forever nodding off to sleep over viciously-parodied excerpts from a sixties kitchen-sink novel. Far too much going on, not much chance of identifying any deeper meaning, but great fun.

20thorold

And back to Japan:

The sound of the mountain (serialised 1949-1954; English 1970) by Yasunari Kawabata (Japan, 1899-1972), translated by Edward Seidensticker (US, 1921-2007)

Kawabata was the first Japanese Nobel laureate in literature. He was associated with the "Shinkankakuha" (new impressions) movement of the inter-war years, reacting against both naturalism and politically-inspired writing. He was also a close friend of Mishima.

Seidensticker was another great Japanese scholar from the US. He was associated with various Japanese and US universities; towards the end of his career he taught at Columbia together with Donald Keene. (I have to be careful what I say here, because I remember Seidensticker's name chiefly from one of the bloodiest battles in the Great Geisha War that took up so much of the first RG Japan thread...)

The sound of the mountain is a slow-moving, lyrical account of a couple of years in the life of a middle-class family living in the historic small town of Kamakura a few years after the end of the war. Shingo, a businessman in his early sixties, is watching rather helplessly whilst just about everything he counts on is slowly crumbling away around him. His mind and body aren’t what they used to be, his son and daughter are both going through difficult patches in their marriages, his own marriage has gone stale, his friends are gradually dying off, and he can’t even take the same pleasure in nature, poetry and the harmonies of Japanese society and religion that he used to. Even the one thing that really does give him pleasure — his close friendship with his daughter-in-law — is a source of guilt to him when he sees that he may be holding her back from resolving the problems she has with her wayward husband.

Despite its very restrained, formal Japanese style, it’s not difficult to identify with Kawabata’s account of the fears and uncertainties that go with approaching old age in a time of destabilised social conditions. Kawabata isn’t known as political and historical writer, but the story here clearly is centred in the particular historical moment when he was writing, with frequent references to current newspaper stories or to people who have been damaged by the war in one way or another.

The sound of the mountain (serialised 1949-1954; English 1970) by Yasunari Kawabata (Japan, 1899-1972), translated by Edward Seidensticker (US, 1921-2007)

Kawabata was the first Japanese Nobel laureate in literature. He was associated with the "Shinkankakuha" (new impressions) movement of the inter-war years, reacting against both naturalism and politically-inspired writing. He was also a close friend of Mishima.

Seidensticker was another great Japanese scholar from the US. He was associated with various Japanese and US universities; towards the end of his career he taught at Columbia together with Donald Keene. (I have to be careful what I say here, because I remember Seidensticker's name chiefly from one of the bloodiest battles in the Great Geisha War that took up so much of the first RG Japan thread...)

The sound of the mountain is a slow-moving, lyrical account of a couple of years in the life of a middle-class family living in the historic small town of Kamakura a few years after the end of the war. Shingo, a businessman in his early sixties, is watching rather helplessly whilst just about everything he counts on is slowly crumbling away around him. His mind and body aren’t what they used to be, his son and daughter are both going through difficult patches in their marriages, his own marriage has gone stale, his friends are gradually dying off, and he can’t even take the same pleasure in nature, poetry and the harmonies of Japanese society and religion that he used to. Even the one thing that really does give him pleasure — his close friendship with his daughter-in-law — is a source of guilt to him when he sees that he may be holding her back from resolving the problems she has with her wayward husband.

Despite its very restrained, formal Japanese style, it’s not difficult to identify with Kawabata’s account of the fears and uncertainties that go with approaching old age in a time of destabilised social conditions. Kawabata isn’t known as political and historical writer, but the story here clearly is centred in the particular historical moment when he was writing, with frequent references to current newspaper stories or to people who have been damaged by the war in one way or another.

21lilisin

because I remember Seidensticker's name chiefly from one of the bloodiest battles in the Great Geisha War that took up so much of the first RG Japan thread...

I haven't laughed this hard in a bit! That was quite the discussion at the end of that thread, wasn't it? But it was a good month of reading!

Can't wait to see your thoughts on the Kawabata. Not an easy author to read what with his very "Japanese style".

I haven't laughed this hard in a bit! That was quite the discussion at the end of that thread, wasn't it? But it was a good month of reading!

Can't wait to see your thoughts on the Kawabata. Not an easy author to read what with his very "Japanese style".

22thorold

>21 lilisin: Yes, it’s almost a shame we don’t manage to get so worked up about what we’re reading any more! Not that it’s all that easy to decode from the earlier thread what the argument was actually about...

I enjoyed the Kawabata more than I expected to, but it did take a while to get into.

I enjoyed the Kawabata more than I expected to, but it did take a while to get into.

23janeajones

Lovely review of the Kawabata. I've only read one of his books. Perhaps I'll pick up this one. I have read much of Seidensticker's translation of Genji.

24thorold

>23 janeajones: Yes, more Kawabata is on the agenda for me too! I'm tempted to have a go at Genji, but it looks like a big time-commitment. I did dip into the Sarashina nikki a little bit over the weekend, but realised that I would need to know a lot more about medieval Japan to get anywhere with it.

Still technically a book by a Japanese writer, but not a very obviously Japanese one:

Etüden im Schnee (2014; Memoirs of a polar bear) by Yōko Tawada (Japan, Germany, 1960- )

Poet, novelist and literary critic Yōko Tawada grew up in Tokyo. She studied Russian and German literature in Tokyo, Hamburg and Zürich, and has lived in Germany, where she has won numerous literary awards, since 1982. She writes in both German (as in the case of this book) and Japanese, with a long list of publications in both languages. Several of her books, including this one, have been translated into English.

Etüden im Schnee is - amongst other things - a book about three (polar) bears and a little girl. But it's the magic-realist three bears novel that you might imagine Günter Grass, Angela Carter and Richard Adams getting together to write. Part one is narrated by the grandmother bear, who is writing her memoirs in between riding a tricycle in a Russian circus; part two is a joint effort by the East German mother bear Toska and her circus trainer Barbara, and part three is again a bear's-eye-view narrated by a slightly-fictionalised version of the greatest real polar-bear-celebrity of our times, Knut of the Berlin Zoo. There's also a guest appearance by a well-known US musician. Although it touches on World War II, the division and reunification of Germany, climate change, and other big topics, this isn't really a political novel - its real focus is on the relationship between people and animals. Tawada tries to get past the anthropomorphism and sentimentality to dig into what is really going on when people interact with animals. Interesting, beautifully written, and technically very ingenious, but I don't know if the result is really worth the effort.

The only obviously Japanese thing about this book was the use of coloured printed paper (with Arctic motifs) for dividers between the chapters, which I thought was a rather nice touch. Less successful was the idea of setting the entire text in Futura. I can't see what that was supposed to achieve - it is a typeface that really doesn't look good when it's packed together to fill a page.

Still technically a book by a Japanese writer, but not a very obviously Japanese one:

Etüden im Schnee (2014; Memoirs of a polar bear) by Yōko Tawada (Japan, Germany, 1960- )

Poet, novelist and literary critic Yōko Tawada grew up in Tokyo. She studied Russian and German literature in Tokyo, Hamburg and Zürich, and has lived in Germany, where she has won numerous literary awards, since 1982. She writes in both German (as in the case of this book) and Japanese, with a long list of publications in both languages. Several of her books, including this one, have been translated into English.

Etüden im Schnee is - amongst other things - a book about three (polar) bears and a little girl. But it's the magic-realist three bears novel that you might imagine Günter Grass, Angela Carter and Richard Adams getting together to write. Part one is narrated by the grandmother bear, who is writing her memoirs in between riding a tricycle in a Russian circus; part two is a joint effort by the East German mother bear Toska and her circus trainer Barbara, and part three is again a bear's-eye-view narrated by a slightly-fictionalised version of the greatest real polar-bear-celebrity of our times, Knut of the Berlin Zoo. There's also a guest appearance by a well-known US musician. Although it touches on World War II, the division and reunification of Germany, climate change, and other big topics, this isn't really a political novel - its real focus is on the relationship between people and animals. Tawada tries to get past the anthropomorphism and sentimentality to dig into what is really going on when people interact with animals. Interesting, beautifully written, and technically very ingenious, but I don't know if the result is really worth the effort.

The only obviously Japanese thing about this book was the use of coloured printed paper (with Arctic motifs) for dividers between the chapters, which I thought was a rather nice touch. Less successful was the idea of setting the entire text in Futura. I can't see what that was supposed to achieve - it is a typeface that really doesn't look good when it's packed together to fill a page.

25thorold

And a bit more background on Japanese literature:

Five modern Japanese novelists (2003) by Donald Keene (USA, Japan, 1922- )

Donald Keene (see >18 thorold: above) shares his memories of five writers he knew personally: Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, Kōbō Abe and Ryutaro Shiba. Each essay neatly mixes Keene's affectionate (sometimes comical, always respectful) first-hand reminiscences with a mini-bio and a brief critical appreciation of his most important works and some notes on how they have been received in Japan and in the West. For the moment, I've only read two of the five, but I found it interesting and useful to read about the others too. There's a good bibliography for anyone seeking to explore in more depth.

I was curious about what Keene would have to say about the Mishima Incident - he takes the line that Mishima's activism had little to do with real right-wing politics but was driven by an aesthetic infatuation with the beauty of sacrifice and early death.

Five modern Japanese novelists (2003) by Donald Keene (USA, Japan, 1922- )

Donald Keene (see >18 thorold: above) shares his memories of five writers he knew personally: Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Yasunari Kawabata, Yukio Mishima, Kōbō Abe and Ryutaro Shiba. Each essay neatly mixes Keene's affectionate (sometimes comical, always respectful) first-hand reminiscences with a mini-bio and a brief critical appreciation of his most important works and some notes on how they have been received in Japan and in the West. For the moment, I've only read two of the five, but I found it interesting and useful to read about the others too. There's a good bibliography for anyone seeking to explore in more depth.

I was curious about what Keene would have to say about the Mishima Incident - he takes the line that Mishima's activism had little to do with real right-wing politics but was driven by an aesthetic infatuation with the beauty of sacrifice and early death.

26janeajones

24> Sounds quite delightful.

27thorold

>26 janeajones: Yes, animal books are hard to resist. And I think this is one of the better ones. Possibly not destined to be added to the canon of great books, but definitely a pleasure to read.

28thorold

...and another very quick Japanese read:

The housekeeper and the professor (2003) by Yōko Ogawa (Japan, 1962- ) translated by Stephen Snyder (USA)

Yōko Ogawa has won a number of major Japanese literary prizes since the 1990s. Several of her books have been made into films and/or translated.

Stephen Snyder has translated books by a number of important Japanese writers, including Kenzaburo Oe and Ryu Murakami.

A charming, subtle, little story about a young single mother who finds herself looking after a retired professor of number theory. As a result of a car accident, the professor has lost his short-term memory, and is unable to recall anything since 1976 if it happened more than eighty minutes ago. Despite this, the woman and her ten-year-old son somehow become close to the old man and learn to share his passion for numbers and for baseball.

Ogawa's butterfly-technique makes this book very attractive to read, but you come out at the end feeling that you haven't really learnt very much about any of the big themes of the book. The maths is what you already know about popular themes like prime numbers and Fermat's last theorem, the baseball probably only makes sense if you're a sports fan, and all you discover about the professor's peculiar mental condition is that it must be very distressing not to be able to recognise the people who matter to you in life: Empathy-lite.

The housekeeper and the professor (2003) by Yōko Ogawa (Japan, 1962- ) translated by Stephen Snyder (USA)

Yōko Ogawa has won a number of major Japanese literary prizes since the 1990s. Several of her books have been made into films and/or translated.

Stephen Snyder has translated books by a number of important Japanese writers, including Kenzaburo Oe and Ryu Murakami.

A charming, subtle, little story about a young single mother who finds herself looking after a retired professor of number theory. As a result of a car accident, the professor has lost his short-term memory, and is unable to recall anything since 1976 if it happened more than eighty minutes ago. Despite this, the woman and her ten-year-old son somehow become close to the old man and learn to share his passion for numbers and for baseball.

Ogawa's butterfly-technique makes this book very attractive to read, but you come out at the end feeling that you haven't really learnt very much about any of the big themes of the book. The maths is what you already know about popular themes like prime numbers and Fermat's last theorem, the baseball probably only makes sense if you're a sports fan, and all you discover about the professor's peculiar mental condition is that it must be very distressing not to be able to recognise the people who matter to you in life: Empathy-lite.

29thorold

Tanizaki sounded like the most interesting of Keene's five novelists that I hadn't got to yet. I read two of the three (short) novels he wrote as newspaper serials in the productive year 1928:

Some prefer nettles (serial 1928-9; English 1955) by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (Japan, 1886-1965), translated by Edward Seidensticker (US, 1921-2007)

In black and white (serial 1928; English 2017) by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (Japan, 1886-1965), translated by Phyllis I. Lyons (US)

Phyllis Lyons is an emeritus professor in Asian languages at Northwestern University. See above for Edward Seidensticker.

Jun'ichirō Tanizaki started out as a real bad-boy writer, dropping out of Tokyo University and financing his exploration of Tokyo's bars and brothels by whatever he could make by dashing off a story here and there. He was besotted with all things western, and - as both Keene and Seidensticker note - furiously pursuing his sexual fantasy of an ideal (un-Japanese) cruel and dominating mistress. After the 1923 earthquake he moved out of Tokyo to live in the Kansai region (Kobe, Kyoto, Osaka), where he started to (re-)discover and learn to appreciate the Japanese cultural values he'd been urging people to sweep away only a few years before. By the time Keene and Seidensticker met him in the fifties, he had become a respected model of the cultured, conservative, Japanese old gentleman.

Some prefer nettles is one of the best-known of Tanizaki's pre-war works. Kaname and Misako feel that their marriage has run its course - Misako is having an affair, Kaname visits "western" brothels - but they can't quite make themselves take the decision to divorce. They both cultivate a westernised, "Tokyo" attitude to life, and are mildly amused by the way Misako's widowed father is immersing himself and his compliant young mistress, O-Hisa in every kind of tradition. But Kaname is captivated, despite himself, when his father-in-law invites them to an Osaka puppet theatre, to the extent that he later goes with him and O-Hisa to an even more authentic (and uncomfortable) performance on Awaji island.

Witty, complicated, and very engaging, even if the unresolved ending is a bit frustrating for anyone used to the way well-plotted western novels work. It would be fun to read this side-by-side with Evelyn Waugh's A handful of dust, written at about the same time and with a very similar plot situation, and a parallel sort of tug-of-war between the modern and the traditional, but resolved in quite a different way.

In black and white, also written in 1928, ran as a successful serial a few months before Some prefer nettles and Quicksand, but for some reason was never re-issued in book form until it appeared in Tanizaki's collected works. It seems to have been largely overlooked until the recent appearance of Phyllis Lyons's English translation.

Mizuno is a struggling young writer living in a Tokyo boarding house and in debt with every bar, whore-house and pawnbroker in the area. He's already sabotaged his marriage by writing a string of wife-murder stories, and now another story, just sent off to the magazine at the last possible moment, looks likely to get him into worse trouble.

His first-person narrator in the story describes getting away with the perfect crime, the motiveless murder of Codama, a man whose link to the narrator is so distant that no-one would suspect his involvement. Unfortunately, in his haste Mizuno has written "Cojima" in several places where he meant "Codama", and he realises that Cojima is in fact a slight acquaintance he must have had in mind whilst he was describing Codama. This mistake will obviously cause embarrassment to him and the magazine if the story is read by anyone who knows Cojima, but Mizuno is worried about something else - what if there's a "Shadow Man" out there somewhere who is out to get him? If Cojima is now murdered, suspicion will automatically fall on Mizuno.

To forestall this, Mizuno works out when the murder would have to take place, and puts in place a comically complex plan to ensure that he is not left without a convincing alibi. Needless to say, it all goes horribly wrong...

Apparently Tanizaki wrote this story in part as a follow-up to a high-profile debate he had had in 1927 with the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa about the relative merits of modernist stream-of-consciousness "I-novels" and tightly-structured plots - it's a kind of literary pastiche in which Mizuno's position as a stream-of-consciousness antihero forces him to craft the literary tools for his own destruction. But it also works well as a crime thriller in its own right, albeit with a rather black kind of humour.

Some prefer nettles (serial 1928-9; English 1955) by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (Japan, 1886-1965), translated by Edward Seidensticker (US, 1921-2007)

In black and white (serial 1928; English 2017) by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki (Japan, 1886-1965), translated by Phyllis I. Lyons (US)

Phyllis Lyons is an emeritus professor in Asian languages at Northwestern University. See above for Edward Seidensticker.

Jun'ichirō Tanizaki started out as a real bad-boy writer, dropping out of Tokyo University and financing his exploration of Tokyo's bars and brothels by whatever he could make by dashing off a story here and there. He was besotted with all things western, and - as both Keene and Seidensticker note - furiously pursuing his sexual fantasy of an ideal (un-Japanese) cruel and dominating mistress. After the 1923 earthquake he moved out of Tokyo to live in the Kansai region (Kobe, Kyoto, Osaka), where he started to (re-)discover and learn to appreciate the Japanese cultural values he'd been urging people to sweep away only a few years before. By the time Keene and Seidensticker met him in the fifties, he had become a respected model of the cultured, conservative, Japanese old gentleman.

Some prefer nettles is one of the best-known of Tanizaki's pre-war works. Kaname and Misako feel that their marriage has run its course - Misako is having an affair, Kaname visits "western" brothels - but they can't quite make themselves take the decision to divorce. They both cultivate a westernised, "Tokyo" attitude to life, and are mildly amused by the way Misako's widowed father is immersing himself and his compliant young mistress, O-Hisa in every kind of tradition. But Kaname is captivated, despite himself, when his father-in-law invites them to an Osaka puppet theatre, to the extent that he later goes with him and O-Hisa to an even more authentic (and uncomfortable) performance on Awaji island.

Witty, complicated, and very engaging, even if the unresolved ending is a bit frustrating for anyone used to the way well-plotted western novels work. It would be fun to read this side-by-side with Evelyn Waugh's A handful of dust, written at about the same time and with a very similar plot situation, and a parallel sort of tug-of-war between the modern and the traditional, but resolved in quite a different way.

In black and white, also written in 1928, ran as a successful serial a few months before Some prefer nettles and Quicksand, but for some reason was never re-issued in book form until it appeared in Tanizaki's collected works. It seems to have been largely overlooked until the recent appearance of Phyllis Lyons's English translation.

Mizuno is a struggling young writer living in a Tokyo boarding house and in debt with every bar, whore-house and pawnbroker in the area. He's already sabotaged his marriage by writing a string of wife-murder stories, and now another story, just sent off to the magazine at the last possible moment, looks likely to get him into worse trouble.

His first-person narrator in the story describes getting away with the perfect crime, the motiveless murder of Codama, a man whose link to the narrator is so distant that no-one would suspect his involvement. Unfortunately, in his haste Mizuno has written "Cojima" in several places where he meant "Codama", and he realises that Cojima is in fact a slight acquaintance he must have had in mind whilst he was describing Codama. This mistake will obviously cause embarrassment to him and the magazine if the story is read by anyone who knows Cojima, but Mizuno is worried about something else - what if there's a "Shadow Man" out there somewhere who is out to get him? If Cojima is now murdered, suspicion will automatically fall on Mizuno.

To forestall this, Mizuno works out when the murder would have to take place, and puts in place a comically complex plan to ensure that he is not left without a convincing alibi. Needless to say, it all goes horribly wrong...

Apparently Tanizaki wrote this story in part as a follow-up to a high-profile debate he had had in 1927 with the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa about the relative merits of modernist stream-of-consciousness "I-novels" and tightly-structured plots - it's a kind of literary pastiche in which Mizuno's position as a stream-of-consciousness antihero forces him to craft the literary tools for his own destruction. But it also works well as a crime thriller in its own right, albeit with a rather black kind of humour.

30janeajones

I enjoyed Some Prefer Nettles, but In Black and White doesn't seem quite my cup of tea.

31kidzdoc

You're doing great with the second quarter Reading Globally theme, Mark. I've read Kokoro, Five Modern Japanese Novelists, The Housekeeper and the Professor, and Some Prefer Nettles, and enjoyed each of them.

32thorold

Finished a couple more books about Japan:

Mishima : ou la vision du vide (1980; Mishima: a vision of the void) by Marguerite Yourcenar (France, Belgium, US, 1903-1987)

Novelist and essayist Marguerite Yourcenar was a distinguished French intellectual and all-round LGBT icon, probably best remembered for her historical novel Mémoires d'Hadrien (1951 - "often bought and rarely finished"). She was born in Belgium, with a French father, and moved to the US (Maine) with her partner Grace Frick in the 1930s (she became a US citizen in 1947). In 1980, the same year as her Mishima essay was published, she became the first woman to be elected to the Académie Française - there have only been 7 others since.