Este tema está marcado actualmente como "inactivo"—el último mensaje es de hace más de 90 días. Puedes reactivarlo escribiendo una respuesta.

1majleavy

Howdy - thought I'd dip a toe in. Don't know that I have much to say: the name is Michael, the profession is high school teacher, the ideology is anarcho-communist.

The books so far for 2017:

1. Debt: the First 5,000 Years, by David Graeber

2. Marx and Human Nature, by Norman Geras

3. Hammered, by Kevin Hearne

4. Tricked, by Kevin Hearne

5. Trapped, by Kevin Hearne

6. To Live and Think Like Pigs, by Gilles Chatelet

7. Trouble in Paradise, by Slavoj Zizek

8. The Chapel Perilous/Two Ravens, One Crow/Grimoire of the Lambs/Two Tales of the Iron Druid Chronicles, by Kevin Hearne

9. The Democracy Project, by David Graeber

10. Pocket Pantheon, by Alain Badiou

11. Foucault and the Politics of Rights, by Ben Golder

Think that's it so far; not a great record-keepr.

Laters.

The books so far for 2017:

1. Debt: the First 5,000 Years, by David Graeber

2. Marx and Human Nature, by Norman Geras

3. Hammered, by Kevin Hearne

4. Tricked, by Kevin Hearne

5. Trapped, by Kevin Hearne

6. To Live and Think Like Pigs, by Gilles Chatelet

7. Trouble in Paradise, by Slavoj Zizek

8. The Chapel Perilous/Two Ravens, One Crow/Grimoire of the Lambs/Two Tales of the Iron Druid Chronicles, by Kevin Hearne

9. The Democracy Project, by David Graeber

10. Pocket Pantheon, by Alain Badiou

11. Foucault and the Politics of Rights, by Ben Golder

Think that's it so far; not a great record-keepr.

Laters.

3drneutron

Welcome! One of the things this group has encouraged me to do is keep a bit better records, so who knows what'll happen! :)

4majleavy

Thanks for the greetings.

Here's the next batch. don't think I'm quite on a 75-book pace:

12. Hunted, by Kevin Hearne

13. Judas Unchained, by Peter Hamilton

14. Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas that Shape the World, by Wade Graham

15. Testerone Rex: Myths of Sex, Science, and Society, by Cordelia Fine

16. The Mark of the Sacred, by Jean-Pierre Dupuy

Here's the next batch. don't think I'm quite on a 75-book pace:

12. Hunted, by Kevin Hearne

13. Judas Unchained, by Peter Hamilton

14. Dream Cities: Seven Urban Ideas that Shape the World, by Wade Graham

15. Testerone Rex: Myths of Sex, Science, and Society, by Cordelia Fine

16. The Mark of the Sacred, by Jean-Pierre Dupuy

7majleavy

April's reads:

17. The Wrong Dead Guy, by Richard Kadrey

18. Materialism, by Terry Eagleton

19. Shattered, by Kevin Hearne

20. An American Utopia, by Frederic Jameson

21. The Incrementalists, by Steven Brust

22. The Skill of Our Hands, by Steven Brust and Skyler White

23. Bound, by Benedict Jacka

24. The History of White People, by Nell Irvin Painter

17. The Wrong Dead Guy, by Richard Kadrey

18. Materialism, by Terry Eagleton

19. Shattered, by Kevin Hearne

20. An American Utopia, by Frederic Jameson

21. The Incrementalists, by Steven Brust

22. The Skill of Our Hands, by Steven Brust and Skyler White

23. Bound, by Benedict Jacka

24. The History of White People, by Nell Irvin Painter

8majleavy

May update:

25. Three Slices, by Ted Hearne, Delilah Dawson, chuck Wendig

26. Staked, by Ted Hearne

27. Money (2nd Rev. Edition), by Eric Lonergan

28. Geometry, by Michel Serres

29. The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, by Franco "Bifo" Birardi

30. Demand the Impossible: A Radical manifesto, by Bill Ayers

31. Wicked as they Come, by Delilah Dawson

32. Shadowbahn, by Steve Erickson

33. White Trash: The 400-Year-Old Untold Story of Class in America, by Nancy Isenberg

34. Ready Player One, by Ernest Cline

25. Three Slices, by Ted Hearne, Delilah Dawson, chuck Wendig

26. Staked, by Ted Hearne

27. Money (2nd Rev. Edition), by Eric Lonergan

28. Geometry, by Michel Serres

29. The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, by Franco "Bifo" Birardi

30. Demand the Impossible: A Radical manifesto, by Bill Ayers

31. Wicked as they Come, by Delilah Dawson

32. Shadowbahn, by Steve Erickson

33. White Trash: The 400-Year-Old Untold Story of Class in America, by Nancy Isenberg

34. Ready Player One, by Ernest Cline

9majleavy

June update:

35. A Paradise Built from Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster, by Rebecca Solnit

36. A Darker Shade of Magic, by V.E. Schwab

37. Kill Society, by Richard Kadrey

38. Foucault with Marx, by Jacques Bidet

39. White Working Class, by Joan C. Williams

40. Wicked As She Wants, by Delilah Dawson

Making this list keeps threatening to alter the way I read - for one thing, I almost never leave a book unfinished, now. Better to waste my time than waste an entry, one part of me thinks. Also, there's a frequent urge to grab up shorter, easier books than what I want to read. I think I've resisted that one so far.

35. A Paradise Built from Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster, by Rebecca Solnit

36. A Darker Shade of Magic, by V.E. Schwab

37. Kill Society, by Richard Kadrey

38. Foucault with Marx, by Jacques Bidet

39. White Working Class, by Joan C. Williams

40. Wicked As She Wants, by Delilah Dawson

Making this list keeps threatening to alter the way I read - for one thing, I almost never leave a book unfinished, now. Better to waste my time than waste an entry, one part of me thinks. Also, there's a frequent urge to grab up shorter, easier books than what I want to read. I think I've resisted that one so far.

12majleavy

It's only been in the last few days that I've found the time to read through some threads and consider the possibility of sharing some thoughts about what I've been reading.

I have no shortage of thoughts - just never have a clue which are worth sharing!

I feel like starting with the two entries on my list that most embarrass me: the "Blud" series by Delilah Dawson.

They embarrass me because they are totally Romance novels, which I never read, and they involve strong-willed, capable heroines who get swept away by stronger-willed, possibly more capable heroes. If you've looked through the entries above, you might be able to guess that I'm way too old-school Feminist to put up with that sort of stuff. Yet, I really enjoy Dawson's story-telling. I encountered her first in an anthology which I read for its Kevin Hearne Iron Druid story, and found myself just swept along by her prose. Tell you what, she's just totally airplane-ride kind of reading; especially if you're down for some Paranormal Romance.

Anyway, each time I read her, I have to at least think back to Cordelia Fine and Testosterone Rex

This is an absorbing book on the widespread myth that testosterone somehow fits men to better compete. A real tonic.

I have no shortage of thoughts - just never have a clue which are worth sharing!

I feel like starting with the two entries on my list that most embarrass me: the "Blud" series by Delilah Dawson.

They embarrass me because they are totally Romance novels, which I never read, and they involve strong-willed, capable heroines who get swept away by stronger-willed, possibly more capable heroes. If you've looked through the entries above, you might be able to guess that I'm way too old-school Feminist to put up with that sort of stuff. Yet, I really enjoy Dawson's story-telling. I encountered her first in an anthology which I read for its Kevin Hearne Iron Druid story, and found myself just swept along by her prose. Tell you what, she's just totally airplane-ride kind of reading; especially if you're down for some Paranormal Romance.

Anyway, each time I read her, I have to at least think back to Cordelia Fine and Testosterone Rex

This is an absorbing book on the widespread myth that testosterone somehow fits men to better compete. A real tonic.

13majleavy

A few words on my most recently completed read, Even the Dead by Benjamin Black:

I hadn't read any of the Quirke novels since the publication of the 5th, Vengeance in 2012 (this is number 7)- as is the case with most series that I tackle, I grow weary of the character and milieu long before the author, publisher, and/or public does - but his latest (Wolf on a String) caught my eye, and I thought I'd return to Quirke before trying the new stand-alone. I think a couple of y'all have read it already?

In short, I enjoyed it, but didn't really find myself lusting for more - Black digs into the latest developments in events begun in the first novel of the series, and it seems tired for that. Still, the prose is fine as always, the story moves, the characters are interesting - I think their conversations are usually the best things in these books - and the ending is upbeat. That, as I recall, is rare for the series, and a sign, perhaps, that the author has exhausted the impulses that got him started with the series, and perhaps the whole "Benjamin Black" identity, in the first place.

As I recall from back in the day, John Banville, one of the greatest of Ireland's 20th century novelists, had begun to find the writing of his literary novels to be increasingly tiresome, and turned to the Black pseudonym and the detective genre, in hopes of writing some works in more or less a single draft. It seemed a good move at the time: his early 21st century works, like The Sea, especially, felt terribly strained and totally lacked the vigor and curiosity of early works like Dr. Copernicus, Kepler, The Newton Letters, or Birchwood. So, the first Quirke, Christine Falls, was a cracking read, and terribly Irish in its focus on family secrets. It's depiction of Dublin in the 50s was rich, as well (although perhaps largely literary? I wasn't there until the 80s, when the physical description still fit, but boy does his Dublin fit the Dublin of Irish writers of the 50s and 60s).

The best of the series, I think, is the second, The Silver Swan, most of all for its absolutely luminous prose. It's the book that most strikingly combines the Banville and Black styles, and I tell you what, almost nobody can write a sentence as fine as Banville can at his best. Plus, it's a fine mystery.

Anyway, this seems to have been more about him and me, than about the book, but then I suppose that it's the relationship between writer and reader that really drives literature, anyway.

14majleavy

Just this morning finished another book, Music After the Fall by Tim Rutherford-Johnson.

I quite enjoyed it and would totally recommend it to anyone interested in the development of art music in the last few decades. The author suggests that music, along with the world, underwent several significant shifts due to things like digitalization, the Internet, the triumph of neoliberalism, and so forth. Rather than looking chronologically, he organizes his chapters thematically: permission, fluidity, excess, and loss. Contains excellent listening and reading guides in the Appendices.

I'm kinda proud to say that I'm down to a mere 3 unread books on my shelf.

Happy 4th to any one who sees this.

I quite enjoyed it and would totally recommend it to anyone interested in the development of art music in the last few decades. The author suggests that music, along with the world, underwent several significant shifts due to things like digitalization, the Internet, the triumph of neoliberalism, and so forth. Rather than looking chronologically, he organizes his chapters thematically: permission, fluidity, excess, and loss. Contains excellent listening and reading guides in the Appendices.

I'm kinda proud to say that I'm down to a mere 3 unread books on my shelf.

Happy 4th to any one who sees this.

15majleavy

Book 39 on my list:

Boy, this is an important book, especially if, like me, you are part of the professional or cultural elite in the US. (Modesty makes me cringe at placing myself among the elite, but as a high school, and former university/college teacher, I pretty much am by default. Plus, I've now and again gotten away with socializing with honest-to-goodness elite intellectuals: world-renowned philosophers! famous science fiction and comic book writers! TV talk show hosts!)

Anyway, this is a book for anyone inclined to think that Trump supporters are, by definition, stupid, deluded, or despicable. It's a quick but careful analysis of how citizens of the "fly-over states" are driven by deep, serious, and honorable values, that we urban elites ignore, discount, or are just generally unaware of, at - as we saw in the past election -our own, and the nation's, peril. Williams counsels us all to start trying to understand each other, and stop the demonizing in which both "sides" are inclined to indulge.

I found it personally trenchant, too. I can expect at dinner this Friday, when I will be with some of my elite friends (a college professor, a writer of several best-sellers, an Emmy-winning/Oscar-nominated director, and their hapless hangers-on (like me)), to hear multiple remarks on how stupid (other) Americans are. This, in spite of the fact that at least three of us are "class migrants," that is to say, born at the bottom of the working class, now resident in the professional or virtuoso classes.

I'll be sure to mention it at dinner, but only one of the other guests will read it.

Boy, this is an important book, especially if, like me, you are part of the professional or cultural elite in the US. (Modesty makes me cringe at placing myself among the elite, but as a high school, and former university/college teacher, I pretty much am by default. Plus, I've now and again gotten away with socializing with honest-to-goodness elite intellectuals: world-renowned philosophers! famous science fiction and comic book writers! TV talk show hosts!)

Anyway, this is a book for anyone inclined to think that Trump supporters are, by definition, stupid, deluded, or despicable. It's a quick but careful analysis of how citizens of the "fly-over states" are driven by deep, serious, and honorable values, that we urban elites ignore, discount, or are just generally unaware of, at - as we saw in the past election -our own, and the nation's, peril. Williams counsels us all to start trying to understand each other, and stop the demonizing in which both "sides" are inclined to indulge.

I found it personally trenchant, too. I can expect at dinner this Friday, when I will be with some of my elite friends (a college professor, a writer of several best-sellers, an Emmy-winning/Oscar-nominated director, and their hapless hangers-on (like me)), to hear multiple remarks on how stupid (other) Americans are. This, in spite of the fact that at least three of us are "class migrants," that is to say, born at the bottom of the working class, now resident in the professional or virtuoso classes.

I'll be sure to mention it at dinner, but only one of the other guests will read it.

16klobrien2

>15 majleavy: Hi, Michael! I found your thread. Oh, there are so many books here that make me sit up and take note. But I have made a start--I have White Working Class on request at my library. It's "on order" so I have a little bit of wait yet.

Karen O.

Karen O.

17majleavy

> klobrien2: Glad you found my thread, Karen. I hope you enjoy White Working Class; I suspect you will.

18majleavy

#33 on my list: White Trash by Nancy Isenberg

#24 on my list: The History of White People by Nell Irvin Painter

In light of >15 majleavy:, I thought I'd recommend two other books I've read in pursuit of better understanding of the US today. As serious historical surveys, both are a bit of a slog to read, but well worth it if the topics interest you.

White Trash goes over the history of racial theorizing by white folk, focusing particularly on the dilemma posed by the fact that certain classes of obviously white people refused to act like white people, as that behavior was defined by the theorists. Thus came a range of notions characterizing those classes as "garbage people," "waste people," and so forth. For the British elite, the New World was an ideal place to send them. From there, Isenberg examines the domestic history of "suspect" white people, the occasional attempts by politicians, a la Andrew Jackson, to court their votes, or to enlist them in the oppression of other groups. She also covers the recuperation of certain later immigrant groups - Irish in particular - from trash people to fully white allies in racist enterprises.

Isenberg helps one understand, among other things, the contemporary irony of modern white supremacists coming mostly from the social class formerly held in serious contempt by generations of white supremacists.

I have to admit that I was raised to use the term "white trash," and have not yet quite freed myself from the pull of the idea. (I remember an amazing double-slur my Italian-American mother once taught me: "Sicilians are the hillbillies of Italy.") And of course, I'm not the only one - among my dining companions tonight will be a pair of class migrants from West Virginia, who can always be counted on for tales of the "regrettable" behavior of their families back home. So, the book was a valuable corrective for me.

History of White People traces the story further back, to the ancient Greeks, and sticks to somewhat broader issues of how white people attempted to figure out just who was white, and why, and how you can tell, and why you'd bother, and how close other groups came to being as cool as white people.

I almost gave the book up a few times - so many theorists and theories! - but I persevered and am the tiny bit smarter for having done so. Which is pretty much what I ask from a book.

19sirfurboy

>18 majleavy: Interesting, particularly about the irony of many modern white supremacists arising from a despised out group of white supremacists! But then, we would not expect too much logic in such group biases.

21majleavy

The best novel I've read in the year's first half:

Shadowbahn by Steve Erickson

I was knocked over the day I saw a new Steve Erickson novel at Barnes and Noble - I don't think I've EVER seen a Steve Erickson novel at Barnes and Noble. Expecting it to disappear at any moment, I rushed it to the counter, whipped out that week's 20% off coupon, then hightailed it down the block to Starbucks, hoping to read the novel before it vanished.

That, I think, was a logical response for a devoted reader of Erickson. Contrary to this novel's first line - "Things don't just disappear into thin -" - in Erickson they do, not just things, but entire histories. And, they also appear out of thin air. In this case, the Twin Towers suddenly intact in the South Dakota badlands.

The towers are empty, except for Jesse Presley, Elvis' stillborn twin. Much of the novel involves his memories of living in a world where it was Elvis who never lived. Throughout, he's haunted by a voice in his head that sounds like his, but can actually sing. In his wanderings, as he becomes increasingly intent on destroying all music, he occasionally encounters people who regard him as if he was the source of a great catastrophe (John Lennon is especially bitter: "Why was it you who lived?"

We also spend time with an adolescent brother and sister, driving with tens of thousands of others to see the towers. The depiction of their relationship is one of the real strengths of the novel:a dazzling portrait of two people who adore each other, but would never say so. As they drive down a highway that never before existed, through a no longer United States, they listen to a cassette prepared by their father. The tunes on the play list are never named, but a number of them are described in a style reminiscent, if I'm not mistaken, of Greil Marcus. The musically literate will derive great pleasure from identifying the tracks. As they progress, they come to find out that that cassette is the only music left in the country.

There are other characters and quests, but the plot, such as it is, is mostly irrelevant. What counts first is the prose - dreamy, musical, haunted - and the slivers of light thrown onto issues such as the relationship of music to identity, music to history, history to nationhood, belief to reality... and, most of all: what happened to America, if, in fact, there ever has been an America that was more than a sometimes-shared dream of a wandering people.

Erickson, to me, is one of America's greatest living novelists, no more than a shade behind Pynchon, DeLillo, and perhaps Oates. Mostly overlooked by readers, he's a favorite of writers. Neil Gaiman is just one of the many greats who cite him as an inspiration. If you demand a vigorous plot, or rigorous narrative logic, pass him by. But for prose that will carry you along breathlessly, and ideas that will trouble you in your quieter moments, he's your man, and this is your book.

Shadowbahn by Steve Erickson

I was knocked over the day I saw a new Steve Erickson novel at Barnes and Noble - I don't think I've EVER seen a Steve Erickson novel at Barnes and Noble. Expecting it to disappear at any moment, I rushed it to the counter, whipped out that week's 20% off coupon, then hightailed it down the block to Starbucks, hoping to read the novel before it vanished.

That, I think, was a logical response for a devoted reader of Erickson. Contrary to this novel's first line - "Things don't just disappear into thin -" - in Erickson they do, not just things, but entire histories. And, they also appear out of thin air. In this case, the Twin Towers suddenly intact in the South Dakota badlands.

The towers are empty, except for Jesse Presley, Elvis' stillborn twin. Much of the novel involves his memories of living in a world where it was Elvis who never lived. Throughout, he's haunted by a voice in his head that sounds like his, but can actually sing. In his wanderings, as he becomes increasingly intent on destroying all music, he occasionally encounters people who regard him as if he was the source of a great catastrophe (John Lennon is especially bitter: "Why was it you who lived?"

We also spend time with an adolescent brother and sister, driving with tens of thousands of others to see the towers. The depiction of their relationship is one of the real strengths of the novel:a dazzling portrait of two people who adore each other, but would never say so. As they drive down a highway that never before existed, through a no longer United States, they listen to a cassette prepared by their father. The tunes on the play list are never named, but a number of them are described in a style reminiscent, if I'm not mistaken, of Greil Marcus. The musically literate will derive great pleasure from identifying the tracks. As they progress, they come to find out that that cassette is the only music left in the country.

There are other characters and quests, but the plot, such as it is, is mostly irrelevant. What counts first is the prose - dreamy, musical, haunted - and the slivers of light thrown onto issues such as the relationship of music to identity, music to history, history to nationhood, belief to reality... and, most of all: what happened to America, if, in fact, there ever has been an America that was more than a sometimes-shared dream of a wandering people.

Erickson, to me, is one of America's greatest living novelists, no more than a shade behind Pynchon, DeLillo, and perhaps Oates. Mostly overlooked by readers, he's a favorite of writers. Neil Gaiman is just one of the many greats who cite him as an inspiration. If you demand a vigorous plot, or rigorous narrative logic, pass him by. But for prose that will carry you along breathlessly, and ideas that will trouble you in your quieter moments, he's your man, and this is your book.

22majleavy

#46:

a book that I'm reading now as a duty rather than a pleasure.

![]() Fools, Frauds, and Firebrands by Roger Scruton.

Fools, Frauds, and Firebrands by Roger Scruton.

I like now and then to read thinkers from the opposite side of the ideological fence, just to keep from getting too ideological my own self. I was hoping this critique of "New Left" thinkers - a number of whom are favorites of mine - would be a good corrective. No such luck.

This is almost pure polemic, and sloppy at that: most of his criticisms of these leftist intellectuals are for the sins of intellectuals across the politico-theoretical spectrum: opaque language, generalized theorizing that ignores everyday realities, occasional claims without real arguments, and so forth. His language, actually, is crystal clear, but you also find that on the far left, Terry Eagleton to name an easy example. He indulges in many drastic over-generalizations about the Left (another common intellectual sin), claiming for instance that they all replace religion with Marxism. That would be pretty offensive to religiously devout far-leftists, like Eagleton or Slavoj Zizek, who believes that communism is only achievable under the aegis of the Holy Spirit.

Two others of his generalizations that weaken his arguments (and then I'll stop): that leftists insist that the economic structure is the source of all social phenomena, and that the New Left dominates academic thinking in the West and Western-attentive nations. For the first, that has been few of very few serious leftist thinkers of the last 75 years or so, and, moreover, is reflected on the right: most neo-liberal and free market thinkers either accord economics a primary role in society, or else seek to reduce all things to economics. As to influence: it may be that the New Left dominates thinking in the Humanities (stress may be), but hardly in our Econ departments. And in the real world it's the neo-liberal thinking dominant there for some decades, that has won out, guiding the World Bank, the IMF, and so forth.

Anyway, you probably weren't planning on reading this book. But if you were, or are someday tempted to: don't. Surely there are still thinkers on the right who rigorously apply principals to real facts, but this guy ain't one of them.

a book that I'm reading now as a duty rather than a pleasure.

I like now and then to read thinkers from the opposite side of the ideological fence, just to keep from getting too ideological my own self. I was hoping this critique of "New Left" thinkers - a number of whom are favorites of mine - would be a good corrective. No such luck.

This is almost pure polemic, and sloppy at that: most of his criticisms of these leftist intellectuals are for the sins of intellectuals across the politico-theoretical spectrum: opaque language, generalized theorizing that ignores everyday realities, occasional claims without real arguments, and so forth. His language, actually, is crystal clear, but you also find that on the far left, Terry Eagleton to name an easy example. He indulges in many drastic over-generalizations about the Left (another common intellectual sin), claiming for instance that they all replace religion with Marxism. That would be pretty offensive to religiously devout far-leftists, like Eagleton or Slavoj Zizek, who believes that communism is only achievable under the aegis of the Holy Spirit.

Two others of his generalizations that weaken his arguments (and then I'll stop): that leftists insist that the economic structure is the source of all social phenomena, and that the New Left dominates academic thinking in the West and Western-attentive nations. For the first, that has been few of very few serious leftist thinkers of the last 75 years or so, and, moreover, is reflected on the right: most neo-liberal and free market thinkers either accord economics a primary role in society, or else seek to reduce all things to economics. As to influence: it may be that the New Left dominates thinking in the Humanities (stress may be), but hardly in our Econ departments. And in the real world it's the neo-liberal thinking dominant there for some decades, that has won out, guiding the World Bank, the IMF, and so forth.

Anyway, you probably weren't planning on reading this book. But if you were, or are someday tempted to: don't. Surely there are still thinkers on the right who rigorously apply principals to real facts, but this guy ain't one of them.

23Storeetllr

Hi, Michael! Thank you for visiting my thread; I hope you come back soon and often! I thought it only right and proper to visit yours in turn.

>22 majleavy: Thank you for reading Fools, Frauds and Firebrands so I don't have to. ;) I know I should be more like you (and, perhaps coincidentally, Rahm Emanuel*) and read books from which I can learn, but I'm tired and barely hanging on emotionally so look instead for escapism. I do like to keep abreast of substantive books and to know what others think is worth reading, just in case I am suddenly overcome with a desire to read something deeper and more meaningful, so your review of these books is helpful and appreciated.

Shadowbahn looks really interesting, if a bit intimidating! I may have to check it out.

*A link to an article about Emanuel's reading preferences was posted over on Mark's (msf59) thread. You may enjoy the article, and it's always nice to visit Mark's threads - he's one of the 75-book group's most prolific members, though I try not to let that intimidate me. http://www.librarything.com/topic/260176#6098261

>22 majleavy: Thank you for reading Fools, Frauds and Firebrands so I don't have to. ;) I know I should be more like you (and, perhaps coincidentally, Rahm Emanuel*) and read books from which I can learn, but I'm tired and barely hanging on emotionally so look instead for escapism. I do like to keep abreast of substantive books and to know what others think is worth reading, just in case I am suddenly overcome with a desire to read something deeper and more meaningful, so your review of these books is helpful and appreciated.

Shadowbahn looks really interesting, if a bit intimidating! I may have to check it out.

*A link to an article about Emanuel's reading preferences was posted over on Mark's (msf59) thread. You may enjoy the article, and it's always nice to visit Mark's threads - he's one of the 75-book group's most prolific members, though I try not to let that intimidate me. http://www.librarything.com/topic/260176#6098261

24PaulCranswick

Welcome to the group Michael.

White Trash looks like it rewards persistence - it seems funny to me in a non-comical way that it was probably that group in US society more than any other that put trump into the White House.

White Trash looks like it rewards persistence - it seems funny to me in a non-comical way that it was probably that group in US society more than any other that put trump into the White House.

25majleavy

>23 Storeetllr: Happy to be of service! I hope the "barely hanging on" is temporary - I certainly encounter such times more than I'd like to. Escapism is probably a quarter of my reading, normally, though that's reliant on the schedules of my favorite series authors. I've got your thread starred - how often I say hello, though, depends on how easily I'm finding it to overcome my shyness at any given time.

>24 PaulCranswick: Hi, Paul, I think it is worth the reading. I failed to interest my dinner companions in it the other night, but they were more interested in pronouncing a big chunk of the population to be stupid, and not much else.

>24 PaulCranswick: Hi, Paul, I think it is worth the reading. I failed to interest my dinner companions in it the other night, but they were more interested in pronouncing a big chunk of the population to be stupid, and not much else.

26Storeetllr

Thanks. I hope it's temporary too. As for being shy, or, as I like to think, introverted, sometimes days go by without my commenting on anyone's (including my own) thread because I feel I have nothing of interest to say, so I get it. I'll be happy if you just visit without commenting unless something strikes your interest and you want to chime in. I will like to hear what you think/how you're doing, but no pressure! That's not what the 75-book group is about.

27majleavy

#37 on my list:

the Kill Society by Richard Kadrey

Doesn't seem to be a lot of Sandman Slim readers in the group (I found only one reference in a search of the group: Berly citing AuntieClio). That surprises me, given all of the genre fans hereabouts. So let me put in a good word:

I picked Sandman Slim up for the first time because of the positive blurbs on the front cover by Charlaine Harris and William Gibson (Kim Harrison and Cory Doctorow, among others, spoke out on the back cover). The story is contemporary, set mostly in LA and Downtown (what those-in-the-know call Hell). The title character was a young practitioner of the magical arts who was sent Downtown by a rival. He's stuck there for a number of years, fighting in the gladiator pits, where his knowledge of magic and his capacity to heal very rapidly makes him a star. In time, he becomes an assassin for one of the major demons, gets a very useful magical object, and returns to LA. There, he runs a video store; because of his access to multiple dimensions, he is able to stock all of the films that were never made here - Jodorowski's Dune, that sort of thing. Over the course of the series, it is more often than not left to Slim and his deeply peculiar, but wonderful, friends to save the world, if not the entire universe.

The series has a hard-boiled tone, kind of like Lawrence Block on hallucinogens, but Slim is on the side of the little guy, so it's okay.

One WARNING: I don't know that this is the sort of thing for someone who is a devout member of one of the Abrahamic faiths - the Creator and all of those Angels of whom you have heard figure as characters, and they don't match up to what I was taught in Catholic grade school, I tell you what.

I won't summarize the book - you gotta start from the beginning of the series - but I'll say that if, like me, you're a fan of Harry Dresden, Alex Verus, John Taylor, or the denizens of Midnight, Texas, you'll probably want Sandman Slim on the list, too.

the Kill Society by Richard Kadrey

Doesn't seem to be a lot of Sandman Slim readers in the group (I found only one reference in a search of the group: Berly citing AuntieClio). That surprises me, given all of the genre fans hereabouts. So let me put in a good word:

I picked Sandman Slim up for the first time because of the positive blurbs on the front cover by Charlaine Harris and William Gibson (Kim Harrison and Cory Doctorow, among others, spoke out on the back cover). The story is contemporary, set mostly in LA and Downtown (what those-in-the-know call Hell). The title character was a young practitioner of the magical arts who was sent Downtown by a rival. He's stuck there for a number of years, fighting in the gladiator pits, where his knowledge of magic and his capacity to heal very rapidly makes him a star. In time, he becomes an assassin for one of the major demons, gets a very useful magical object, and returns to LA. There, he runs a video store; because of his access to multiple dimensions, he is able to stock all of the films that were never made here - Jodorowski's Dune, that sort of thing. Over the course of the series, it is more often than not left to Slim and his deeply peculiar, but wonderful, friends to save the world, if not the entire universe.

The series has a hard-boiled tone, kind of like Lawrence Block on hallucinogens, but Slim is on the side of the little guy, so it's okay.

One WARNING: I don't know that this is the sort of thing for someone who is a devout member of one of the Abrahamic faiths - the Creator and all of those Angels of whom you have heard figure as characters, and they don't match up to what I was taught in Catholic grade school, I tell you what.

I won't summarize the book - you gotta start from the beginning of the series - but I'll say that if, like me, you're a fan of Harry Dresden, Alex Verus, John Taylor, or the denizens of Midnight, Texas, you'll probably want Sandman Slim on the list, too.

28majleavy

A book I couldn't finish, plus some I did:

DNF Cory Doctorow's Walkaway, #1 David Graeber's Debt: the First 5,000 Years, #35 Rebecca Solnit's A Paradise Built in Hell

I really wanted to enjoy this book - as Kim Stanley Robinson says on the back cover, Doctorow is writing "the hard utopia" in "a world full of easy dystopias" - and since the vision is anarcho-communist, pretty much, it's right up my alley. Unfortunately, the amount of time devoted to lengthy dialogues about how the anarchist system can/should/will work slows things down, and somehow makes the action/thriller elements seem out of place and off-kilter. Characters never quite hit the level of plausible or interesting, either, with quirks and/or self-analysis replacing a realized personality.

The walkaway of the title involves people abandoning the "Default" world of pointless work and acquisition and joining like-minded others in the wilderness. It's near-future, when technology had removed us even further than we are now from the actual need for anyone to go without, or to do de-humanizing work just to squeak by. The foremost character (at least through the first 170 pages) is the daughter of one of the super-rich who goes walkaway almost as a lark after a "communist party" (a party where everything, including location and self-replicating beer, is appropriated and shared with all comers) ends in disaster. She, and the rest of the walkaway community are subject to a good deal of violence from those who cannot afford to let the world know that we can live without bosses of any sort, if enough of us choose not to.

Obviously, I don't know how it ends - but I'm guessing triumph for the walkaways.

I guess utopias are always optimistic at heart, anarchist ones especially, since the whole premise is that people are by nature cooperative. As I was reading, I kept flashing back to both the Solnit and Graeber books above, since they each advance, with ample evidence, the notion that this is the case, and are both excellent books.

Solnit looks at the aftermath of a number of natural disasters, which typically reveal the open-hearted cooperation of the survivors, which eventually gets squashed as the authorities treat the populace as enemies in the attempt to restore order - by which they mean, control. Graeber's work is mostly on the role of debt as a technology of exploitation, but the early sections examine the anthropological & historical evidence for credit as the earliest economic system, which in pre-money terms means that sharing, reciprocity, and social ties are the predominant forces. Anyway, both of these books are fascinating; Solnit is the easier read, with more storytelling and lively incident.

I was moved to pick up Walkaway in large part by the blurbs on the back cover: praise from William Gibson, Edward Snowden, Kim Stanley Robinson, and Neal Stephenson. Three of those four were favorite authors upon a time... but I forgot that it's been years since I've actually enjoyed their work. Stephenson and l Robinson especially grew way too slack in their storytelling for me. If you still enjoy them, you may want to place their recommendations over my lack thereof.

DNF Cory Doctorow's Walkaway, #1 David Graeber's Debt: the First 5,000 Years, #35 Rebecca Solnit's A Paradise Built in Hell

I really wanted to enjoy this book - as Kim Stanley Robinson says on the back cover, Doctorow is writing "the hard utopia" in "a world full of easy dystopias" - and since the vision is anarcho-communist, pretty much, it's right up my alley. Unfortunately, the amount of time devoted to lengthy dialogues about how the anarchist system can/should/will work slows things down, and somehow makes the action/thriller elements seem out of place and off-kilter. Characters never quite hit the level of plausible or interesting, either, with quirks and/or self-analysis replacing a realized personality.

The walkaway of the title involves people abandoning the "Default" world of pointless work and acquisition and joining like-minded others in the wilderness. It's near-future, when technology had removed us even further than we are now from the actual need for anyone to go without, or to do de-humanizing work just to squeak by. The foremost character (at least through the first 170 pages) is the daughter of one of the super-rich who goes walkaway almost as a lark after a "communist party" (a party where everything, including location and self-replicating beer, is appropriated and shared with all comers) ends in disaster. She, and the rest of the walkaway community are subject to a good deal of violence from those who cannot afford to let the world know that we can live without bosses of any sort, if enough of us choose not to.

Obviously, I don't know how it ends - but I'm guessing triumph for the walkaways.

I guess utopias are always optimistic at heart, anarchist ones especially, since the whole premise is that people are by nature cooperative. As I was reading, I kept flashing back to both the Solnit and Graeber books above, since they each advance, with ample evidence, the notion that this is the case, and are both excellent books.

Solnit looks at the aftermath of a number of natural disasters, which typically reveal the open-hearted cooperation of the survivors, which eventually gets squashed as the authorities treat the populace as enemies in the attempt to restore order - by which they mean, control. Graeber's work is mostly on the role of debt as a technology of exploitation, but the early sections examine the anthropological & historical evidence for credit as the earliest economic system, which in pre-money terms means that sharing, reciprocity, and social ties are the predominant forces. Anyway, both of these books are fascinating; Solnit is the easier read, with more storytelling and lively incident.

I was moved to pick up Walkaway in large part by the blurbs on the back cover: praise from William Gibson, Edward Snowden, Kim Stanley Robinson, and Neal Stephenson. Three of those four were favorite authors upon a time... but I forgot that it's been years since I've actually enjoyed their work. Stephenson and l Robinson especially grew way too slack in their storytelling for me. If you still enjoy them, you may want to place their recommendations over my lack thereof.

29majleavy

Oh, I just realized that, by setting aside Walkaway, I achieved a certain, perhaps ironic, freedom: I have no unread or unfinished book on my shelves (or on the floor, for that matter). Unless you count Owner's Manuals and User's Guides; I got them scattered everywhere, especially under the dust.

Fortunately: Kindle. Time for some John Crowley, whom I haven't read in years.

The problem with Kindle, though: In the previous message, I credited Graeber with ideas that might actually belong to Eric Lonergan, but I read both books on Kindle, so I couldn't grab them off the shelve to confirm!

Fortunately: Kindle. Time for some John Crowley, whom I haven't read in years.

The problem with Kindle, though: In the previous message, I credited Graeber with ideas that might actually belong to Eric Lonergan, but I read both books on Kindle, so I couldn't grab them off the shelve to confirm!

30weird_O

Hi, Michael. You stopped by my thread; I'm returning the visit. For a guy spurning short reads, you certainly are making strides toward 75, although >29 majleavy: makes it sound like you've run out of books. Nothing to read.

31majleavy

>30 weird_O: I was out of books for, like, an hour... Refreshed my Kindle with John Crowley's Solitudes (first published as Aegypt), then today picked up a pair of non-fictions at a bookstore: The Violence of Organized Forgetting, Henri Giroux, and The Agony of Eros, Byung-Hul Chan. So I'm back in the game. Thanks for stopping by.

32majleavy

A couple of recent reads about which I have said nothing:

#44

This has been reviewed on other threads, I think, so I'll be brief. Snyder, an historian, points out what is often overlooked, that the 20th was a rough century on democracies. He points to the many collapses of democratic states established during the century's 3 "democratic moments": after the first first and second world wars, and after the fall of communism. From these he takes 20 lessons which any and all of us can follow to help prevent a slide into totalitarianism in the remaining democracies. These lessons - Do Not Obey in Advance and Believe in Truth, for example - are each addressed in concise, highly specific chapters. Snyder clearly takes President Trump to represent a real step in the direction of totalitarianism, but for reasons that the traditional right will appreciate as much as the current left.

Totally recommended to anyone who cares about freedom - the sort of book that you'll want to hand out to other people and say, "do these things."

#48

Well, the title could describe how we faithful children of the Republic feel in these times, but the book has nothing what to do with it.

Readers of the Iron Druid Chronicles will recognize the standard past-tense-verb title of the series, along with the Gene Mollica cover art (the Druid, strangely, is rather more baby-faced than on the previous books). If you don't know the series, it involves the last remaining Druid, who has used his wits, earth-based magic, martial arts skills, and an immortality potion to stay alive for several millenia (by this point in the series, he is no longer the sole living Druid). The first of the series starts with a fight-to-the death with an Irish God, and before too long the Druid is throwing down with dieties from a range of pantheons, often with the dieties of other (even the same) pantheons at his side. It's all good, violent fun, with vampires, werewolves, witches, and all your other favorite un- and super-naturals thrown in the mix. Pretty funny, as well.

This volume is a set of short stories, entertaining for the faithful, but if you haven't dipped into the Chronicles yet, this would not be the place.

And, as with the Sandman Slim book I reviewed a few posts ago - be warned if you are devout. Jesus has made several appearances, and his mother has visited at least once. When I was a wee lad, my own mother warned me, "never read a book you wouldn't be willing to show the Virgin." I'd have no problem sharing this with her, but my version of the Virgin may be more relaxed than others'. Could be, too, that members of traditions outside the Abrahamic might take issue with the use of Coyote, or of Hindu and African gods...

#44

This has been reviewed on other threads, I think, so I'll be brief. Snyder, an historian, points out what is often overlooked, that the 20th was a rough century on democracies. He points to the many collapses of democratic states established during the century's 3 "democratic moments": after the first first and second world wars, and after the fall of communism. From these he takes 20 lessons which any and all of us can follow to help prevent a slide into totalitarianism in the remaining democracies. These lessons - Do Not Obey in Advance and Believe in Truth, for example - are each addressed in concise, highly specific chapters. Snyder clearly takes President Trump to represent a real step in the direction of totalitarianism, but for reasons that the traditional right will appreciate as much as the current left.

Totally recommended to anyone who cares about freedom - the sort of book that you'll want to hand out to other people and say, "do these things."

#48

Well, the title could describe how we faithful children of the Republic feel in these times, but the book has nothing what to do with it.

Readers of the Iron Druid Chronicles will recognize the standard past-tense-verb title of the series, along with the Gene Mollica cover art (the Druid, strangely, is rather more baby-faced than on the previous books). If you don't know the series, it involves the last remaining Druid, who has used his wits, earth-based magic, martial arts skills, and an immortality potion to stay alive for several millenia (by this point in the series, he is no longer the sole living Druid). The first of the series starts with a fight-to-the death with an Irish God, and before too long the Druid is throwing down with dieties from a range of pantheons, often with the dieties of other (even the same) pantheons at his side. It's all good, violent fun, with vampires, werewolves, witches, and all your other favorite un- and super-naturals thrown in the mix. Pretty funny, as well.

This volume is a set of short stories, entertaining for the faithful, but if you haven't dipped into the Chronicles yet, this would not be the place.

And, as with the Sandman Slim book I reviewed a few posts ago - be warned if you are devout. Jesus has made several appearances, and his mother has visited at least once. When I was a wee lad, my own mother warned me, "never read a book you wouldn't be willing to show the Virgin." I'd have no problem sharing this with her, but my version of the Virgin may be more relaxed than others'. Could be, too, that members of traditions outside the Abrahamic might take issue with the use of Coyote, or of Hindu and African gods...

33Storeetllr

>32 majleavy: I need to read both of these!

ETA I love Hearne's Jesus. I don't remember the Virgin's appearance though.

ETA I love Hearne's Jesus. I don't remember the Virgin's appearance though.

34majleavy

>33 Storeetllr: In the second book, Hexed. Atticus has Katie pray for an appearance, so he can get some arrows blessed before going after a demon. I think that's the only time.

Enjoy them both, when you get to them!

Enjoy them both, when you get to them!

35Storeetllr

Hah! Probably why I didn't remember. I read that one a few years ago (early 2014). May be time for a reread of the series.

36majleavy

And talking of re-reading: I was just adding some old books to My Library (which is terribly incomplete), and was reminded of an old favorite that I often think of re-reading, and probably will soon:

God's Fires by Patricia Anthony.

Such an awesome and beautiful book, by a great, too-little-known author. The plot: an alien space ship crashes in Portugal, during the Spanish Inquisition. Are they angels? Demons? The Inquisition is determined to discover. As is the weak-minded boy king, and everyone else. The themes are sublime, but the book is elemental: herb-craft, and sex, and soil, and torture, and penance, and death in prison. I read it 20 years ago, but it still feels vivid in the mind.

Anyway, taste this opening paragraph:

Fornication. It was not a sin he expected her to confess. Not her. Not she of the Three Hairy Moles. Father Manoel Pessoa's gasp tasted of Dona Inez: a reek of stale goat cheese and decomposing sardines. The resulting cough saved him from laughter, or shattering the silence of the church by blurting: "Holy Jesus! With whom?

God's Fires by Patricia Anthony.

Such an awesome and beautiful book, by a great, too-little-known author. The plot: an alien space ship crashes in Portugal, during the Spanish Inquisition. Are they angels? Demons? The Inquisition is determined to discover. As is the weak-minded boy king, and everyone else. The themes are sublime, but the book is elemental: herb-craft, and sex, and soil, and torture, and penance, and death in prison. I read it 20 years ago, but it still feels vivid in the mind.

Anyway, taste this opening paragraph:

Fornication. It was not a sin he expected her to confess. Not her. Not she of the Three Hairy Moles. Father Manoel Pessoa's gasp tasted of Dona Inez: a reek of stale goat cheese and decomposing sardines. The resulting cough saved him from laughter, or shattering the silence of the church by blurting: "Holy Jesus! With whom?

37majleavy

Books 21 and 22: belated reviews

The Incrementalists by Steven Brust and The Skill of Our Hands by Steven Brust and Skyler White Tom Doherty Associates for Tor Hardcover

Succinct judgment:

Totally recommended for fans of serious science fiction. Actually, no science and totally earthbound, involving the efforts of (to quote) "a secret society of 200 people - an unbroken lineage reaching back forty thousand years," who have been attempting to guide humankind via countless incremental little changes. You'll probably like these if you're a fan of Daniel O'Malley's Rook series, or maybe even Simon R. Green's Secret Histories series (but wished they were way way more serious and realistic).

John Scalzi and Roger Zelazney are among those who have offered praise.

More verbose comments:

I really enjoyed the first in the series, and absolutely loved the second. The premise is that these 200 individuals can move into new host bodies when they die. The process usually erases the personality of the host, but sometimes there is a blend, and occasionally, it's the host personality that takes over. The main character is Phil, who has remained a stable personality for longer than any of the others, and each of the books features a crisis for him that, of course effects them all and, perhaps, all of us. In each case, the senior members gather to resolve things.

This is an intricately drawn conception, with the Incrementalists able to occupy a shared mental space, in which each of them has a garden where all of their memories are planted and available to the rest. The big thematic issue is, of course: what right do any of us have to attempt to influence others or even, ultimately, to attempt to change things at all. A deep issue that touches a lot of us and is brought much more to the fore in the second book. The Skill of Our Hands begins with Phil dead, shot by persons unknown. I won't say what he was up to, but the issues addressed are the surveillance state in which we live and the associated para-militarization of police departments nationwide. A compelling and skillfully told story, an additional conceit of the book is that it represents the going-public of the Incrementalists. The senior member who has written it concludes with a stirring peroration, which reads in part: "Get involved. Make things better... Yours are the hands on those machines. Think about what than means."

(The final sentences refer to a favorite song of Phil's, sung to the tune of When Johnny Comes Marching Home: Mighty the engine, vast the field/From coast to coast/The skill of our hands, they wealth they yield/Is all earth's boast/For ours are the hands on those machines/Just think for a minute of what that means./And the time will come we'll not be fooled anymore.)

A number of folks in the group, I gather, have read the book that maybe tells us how to make things better in this time and these places: On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century.

The Incrementalists by Steven Brust and The Skill of Our Hands by Steven Brust and Skyler White Tom Doherty Associates for Tor Hardcover

Succinct judgment:

Totally recommended for fans of serious science fiction. Actually, no science and totally earthbound, involving the efforts of (to quote) "a secret society of 200 people - an unbroken lineage reaching back forty thousand years," who have been attempting to guide humankind via countless incremental little changes. You'll probably like these if you're a fan of Daniel O'Malley's Rook series, or maybe even Simon R. Green's Secret Histories series (but wished they were way way more serious and realistic).

John Scalzi and Roger Zelazney are among those who have offered praise.

More verbose comments:

I really enjoyed the first in the series, and absolutely loved the second. The premise is that these 200 individuals can move into new host bodies when they die. The process usually erases the personality of the host, but sometimes there is a blend, and occasionally, it's the host personality that takes over. The main character is Phil, who has remained a stable personality for longer than any of the others, and each of the books features a crisis for him that, of course effects them all and, perhaps, all of us. In each case, the senior members gather to resolve things.

This is an intricately drawn conception, with the Incrementalists able to occupy a shared mental space, in which each of them has a garden where all of their memories are planted and available to the rest. The big thematic issue is, of course: what right do any of us have to attempt to influence others or even, ultimately, to attempt to change things at all. A deep issue that touches a lot of us and is brought much more to the fore in the second book. The Skill of Our Hands begins with Phil dead, shot by persons unknown. I won't say what he was up to, but the issues addressed are the surveillance state in which we live and the associated para-militarization of police departments nationwide. A compelling and skillfully told story, an additional conceit of the book is that it represents the going-public of the Incrementalists. The senior member who has written it concludes with a stirring peroration, which reads in part: "Get involved. Make things better... Yours are the hands on those machines. Think about what than means."

(The final sentences refer to a favorite song of Phil's, sung to the tune of When Johnny Comes Marching Home: Mighty the engine, vast the field/From coast to coast/The skill of our hands, they wealth they yield/Is all earth's boast/For ours are the hands on those machines/Just think for a minute of what that means./And the time will come we'll not be fooled anymore.)

A number of folks in the group, I gather, have read the book that maybe tells us how to make things better in this time and these places: On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century.

38drneutron

Was gonna add The Incrementalists to my list, then found out that it's already there! Glad you liked it.

39majleavy

>38 drneutron: Glad it's on your list!

40Storeetllr

It's on mine now, too! Thanks for bringing it to my attention!

41majleavy

>40 Storeetllr: Hi Mary. I think you and the drneutron will both enjoy it. Hope so.

42majleavy

My reading plans for the next few weeks (especially on the flight from LA to Santa Fe, NM, where I'll be vacationing next week):

Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Pedagogy of Hope to get ready for the new teaching year at a new high school.

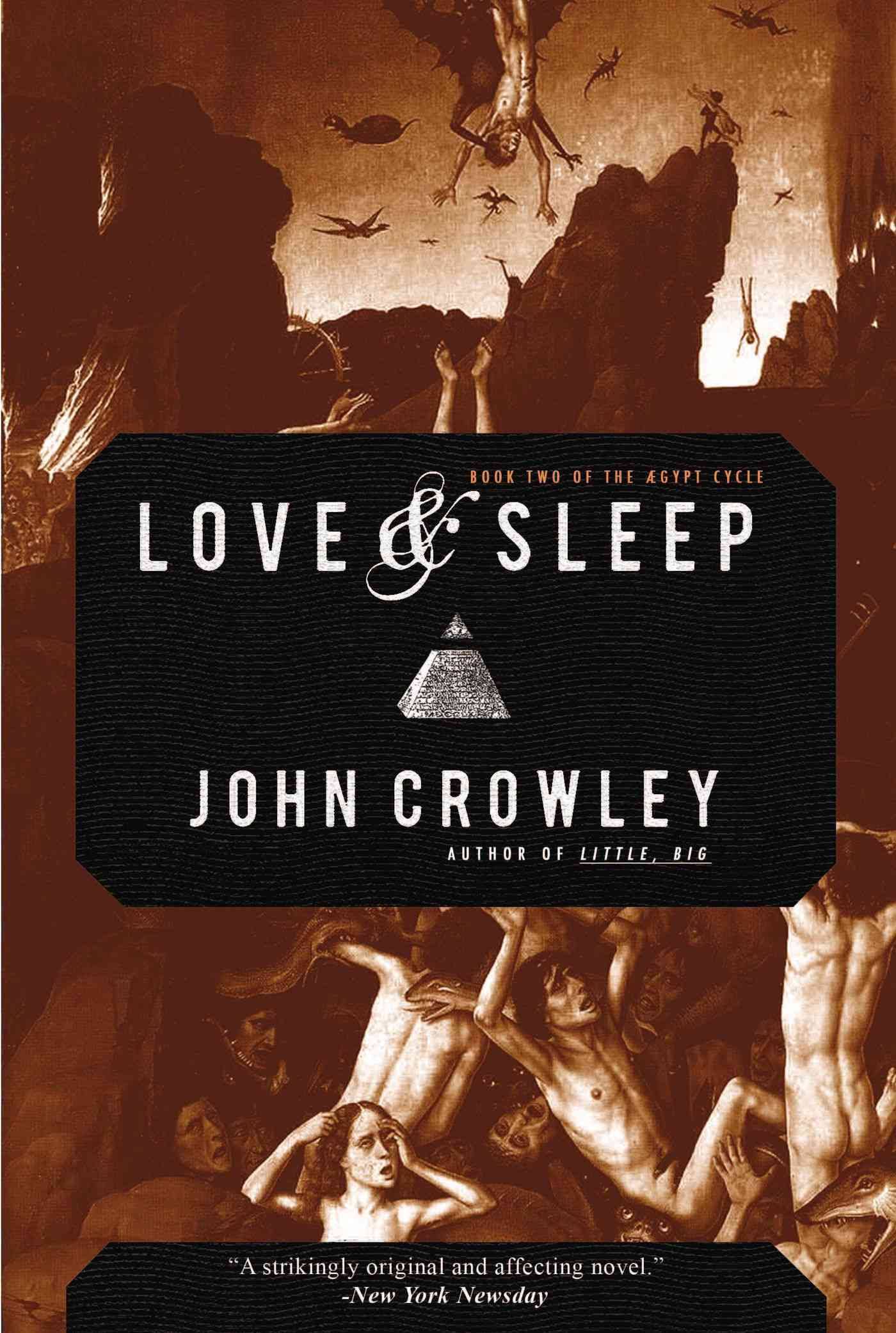

The 2nd, 3rd, and 4th volumes of the AEgypt tetratology by John Crowley, to wallow in beautiful prose and enchanting ideas before having to swallow the painful prose and sometime enchanting ideas of my students.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Pedagogy of Hope to get ready for the new teaching year at a new high school.

The 2nd, 3rd, and 4th volumes of the AEgypt tetratology by John Crowley, to wallow in beautiful prose and enchanting ideas before having to swallow the painful prose and sometime enchanting ideas of my students.

43majleavy

Finished two books today. Here's the good one:

The Solitudes, John Crowley (originally published as AEgypt (#50 for the year)

The Succinct Judgment

I can warmly recommend this one to anyone who enjoys thoughtful fantasy, more about wistful and epic ideas than about battles and creatures (well, there are angels and daemons). It involves a historian on a quest to discover/remember the other history of the world, the one that was real before the history we have now replaced it. That other history is the one only glimpsed in obscure books, when Egypt was AEgypt, home to Hermes Trismegistus who created the hieroglyphs that, like a Memory Palace, contained all the Truth that there was. A gyre of the book, spinning from New York classrooms, to the Faraway Hills of New York state, to the England of Dr. John Dee, to the heretic Giordano Bruno's infinite universe in which everyone is like God, if only they would remember. If you are a Neil Gaiman fan, as I know many group members are, it's a good bet that you will enjoy this one.

If you care, Harold Bloom included The Solitudes and it's sequel in the Canon of Western Literature. Gaiman himself has called Crowley's previous book, Little, Big, "one of my favorite books in the world," and, to my mind, The Solitudes is only slightly less wonderful than that one.

The Longer Consideration

Somewher in the middle of Neil Gaimans' The Sandman series, there was a stand-alone story called "The Dream of a Thousand Cats," or somesuch. The conceit was that, once the world was ruled by cats, and people were just tiny creatures, their prey and playthings. But, one night, one thousand people all dreamt of a different world, where they were in charge, and when they awoke, so it was, and always had been. Some cats, though, remember that other history, and know that it could be restored, if only a thousand cats could all dream of it. Fat chance of that happening, of course, cats being as willful as they are.

Something similar is the conceit of The Solitudes, that the world has had more than one history, and sometimes people catch glimpses of it, in books and in dreams.

The main character (Pierce Moffet) is one of those people, a failed historian, specializing in the Renaissance, who ends up leaving New York City to move to Blackbury Jambs in the Faraway Hills of upstate New York, thinking to write a book revealing that other history. Faraway Hills, it turns out, was the home of historical novelist Fellowes Kraft, whose novels Pierce had read as child in the backwoods of Kentucky. That frame is fleshed out with the daily lives and backstories of a number of characters - all of them told with just a hint of fairy tale and legend - and excerpts from Kraft's novels about Shakespeare, Elizbeht I's astrologer John Dee, and Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake in the 16th century for, among other things, conceiving of the universe as infinite and co-extensive with God Himself.

I can't really convey how rich and untimately inspiring this book is, enraptured with the possibility that maybe, once, it really was true that the whole Universe was alive, and all of it intelligent, and that the wise could, simply by naming the truth, work great magic. It's all driven, I suppose, by the longing that animated the Harry Potter series: the sense that, really, this world we live in is not the one we were meant to live in, that there is something else. It also is a book about books, about reading and the transportation of the imagination, and - like so much of Gaiman's work - about why we tell stories.

This was a re-read for me. I first read it, under the title AEgypt, when it first came out in 1987. I was a huge fan of Crowley's: his previous novel, Little, Big seemed to me the most beautiful novel I had ever read, and the novel before that, Engine Summer broke my heart like no other novel ever ever has. AEgypt was the last novel of his that I ever saw on a bookstore shelf, and I either never new or had long ago forgotten that it had successors. I recently found out that he had written quite a bit since then, and so want to now to finish the cycle.

The Solitudes, John Crowley (originally published as AEgypt (#50 for the year)

The Succinct Judgment

I can warmly recommend this one to anyone who enjoys thoughtful fantasy, more about wistful and epic ideas than about battles and creatures (well, there are angels and daemons). It involves a historian on a quest to discover/remember the other history of the world, the one that was real before the history we have now replaced it. That other history is the one only glimpsed in obscure books, when Egypt was AEgypt, home to Hermes Trismegistus who created the hieroglyphs that, like a Memory Palace, contained all the Truth that there was. A gyre of the book, spinning from New York classrooms, to the Faraway Hills of New York state, to the England of Dr. John Dee, to the heretic Giordano Bruno's infinite universe in which everyone is like God, if only they would remember. If you are a Neil Gaiman fan, as I know many group members are, it's a good bet that you will enjoy this one.

If you care, Harold Bloom included The Solitudes and it's sequel in the Canon of Western Literature. Gaiman himself has called Crowley's previous book, Little, Big, "one of my favorite books in the world," and, to my mind, The Solitudes is only slightly less wonderful than that one.

The Longer Consideration

Somewher in the middle of Neil Gaimans' The Sandman series, there was a stand-alone story called "The Dream of a Thousand Cats," or somesuch. The conceit was that, once the world was ruled by cats, and people were just tiny creatures, their prey and playthings. But, one night, one thousand people all dreamt of a different world, where they were in charge, and when they awoke, so it was, and always had been. Some cats, though, remember that other history, and know that it could be restored, if only a thousand cats could all dream of it. Fat chance of that happening, of course, cats being as willful as they are.

Something similar is the conceit of The Solitudes, that the world has had more than one history, and sometimes people catch glimpses of it, in books and in dreams.

The main character (Pierce Moffet) is one of those people, a failed historian, specializing in the Renaissance, who ends up leaving New York City to move to Blackbury Jambs in the Faraway Hills of upstate New York, thinking to write a book revealing that other history. Faraway Hills, it turns out, was the home of historical novelist Fellowes Kraft, whose novels Pierce had read as child in the backwoods of Kentucky. That frame is fleshed out with the daily lives and backstories of a number of characters - all of them told with just a hint of fairy tale and legend - and excerpts from Kraft's novels about Shakespeare, Elizbeht I's astrologer John Dee, and Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake in the 16th century for, among other things, conceiving of the universe as infinite and co-extensive with God Himself.

I can't really convey how rich and untimately inspiring this book is, enraptured with the possibility that maybe, once, it really was true that the whole Universe was alive, and all of it intelligent, and that the wise could, simply by naming the truth, work great magic. It's all driven, I suppose, by the longing that animated the Harry Potter series: the sense that, really, this world we live in is not the one we were meant to live in, that there is something else. It also is a book about books, about reading and the transportation of the imagination, and - like so much of Gaiman's work - about why we tell stories.

This was a re-read for me. I first read it, under the title AEgypt, when it first came out in 1987. I was a huge fan of Crowley's: his previous novel, Little, Big seemed to me the most beautiful novel I had ever read, and the novel before that, Engine Summer broke my heart like no other novel ever ever has. AEgypt was the last novel of his that I ever saw on a bookstore shelf, and I either never new or had long ago forgotten that it had successors. I recently found out that he had written quite a bit since then, and so want to now to finish the cycle.

44majleavy

This is the other book I finished yesterday:

The Violence of Organized Forgetting by Henry A. Giroux

The Quick Word:

Don't read it. This book, which seems to aim at a description of how media in the US is normalizing neoliberal hegemony, is a dense and tiring rant about how neoliberalism is destroying democracy in the US. I don't disagree with it at all, but boyoboy is it wearying.

Actually, you might want to give it look if you've even been curious about how Noam Chomsky would sound it he were ramped up on some serious amphetamines. Or if you feel compelled to touch base with the work of one of The Toronto Star's "twelve Canadians changing the way we think."

The Longer Look

The topic is of utmost importance: Americans are forgetting what it means to live in a democracy. The ever-quickening transformation of citizens into consumers, of communities into populations of self-fulfillment-seeking monads, is wreaking havoc on the public sphere required for the maintenance of democratic institutions. But the book is over-generalized and over-assertive, nearly devoid of analysis or examples, and totally fails to make good on what would seem to be the only justification for having written the book: an analysis of how the media ("America's disimagination machine") is eroding our capacity to imagine a different world than the one we have.

If the topic of neoliberalism and its effects are of interest to you, David Harvey's A Brief History of Neoliberalism is a good bet.

The Violence of Organized Forgetting by Henry A. Giroux

The Quick Word:

Don't read it. This book, which seems to aim at a description of how media in the US is normalizing neoliberal hegemony, is a dense and tiring rant about how neoliberalism is destroying democracy in the US. I don't disagree with it at all, but boyoboy is it wearying.

Actually, you might want to give it look if you've even been curious about how Noam Chomsky would sound it he were ramped up on some serious amphetamines. Or if you feel compelled to touch base with the work of one of The Toronto Star's "twelve Canadians changing the way we think."

The Longer Look

The topic is of utmost importance: Americans are forgetting what it means to live in a democracy. The ever-quickening transformation of citizens into consumers, of communities into populations of self-fulfillment-seeking monads, is wreaking havoc on the public sphere required for the maintenance of democratic institutions. But the book is over-generalized and over-assertive, nearly devoid of analysis or examples, and totally fails to make good on what would seem to be the only justification for having written the book: an analysis of how the media ("America's disimagination machine") is eroding our capacity to imagine a different world than the one we have.

If the topic of neoliberalism and its effects are of interest to you, David Harvey's A Brief History of Neoliberalism is a good bet.

45majleavy

#51 on the finished list:

The Agony of Eros by Byung-Chul Han, translated by Erik Butler. MIT Press.

The Quick Version

This is a really interesting book (and short - 56 pages!). Han, a Korean-German philosopher, advances the view that our modern "achievement society" is killing love. In a nutshell, his premise is that we are increasingly imprisoned in a culture of "positivity," encouraged to accumulate goods, accomplishments, experiences, and pleasures; this forecloses our availability to the "negation" required by love.

Han uses the terms "positive" and "negative" in a slightly non-standard way. The positive is the category of the countable, the visible, the accessible, or recognizable. The negative is the territory of the unknown, the risk, the loss. If love, as he claims, requires the willingness to surrender the Self to the unknowable Other, to be fully vulnerable to possibilities, then a devotion to positivity prevents us from ever making the journey from self to loss-of-self to a new, enriched self.

Further Commentary

Han is a German philosopher, so 56 pages takes longer to read than you might think. Still, he writes a very lucid prose - aside from some specialized terminology. His topic is Love, but he extends the analysis at points to Politics, Science, and Art. These four categories are taken from Alain Badiou, who designates them as the only four spheres in which a true Event can occur - Event being the irruption into the world of something previously impossible. For Badiou, the quintessential event is the Incarnation of Christ (surprisingly, perhaps, since Badiou is an atheist), but falling in love is the Event to which we all have access. For Badiou and Han, the only Well-lived life is one that exhibits faithfulness to an Event.

Anyway, Han's primary target is neoliberalism and its peripherals: first for its over-riding demand to consume and to accumulate; second for its intensification of a long-developing Western individualism that turns us ever more inward and brings us to look at others as mirrors (fun-house or otherwise) of ourselves. Implicated in this is intensifying "care of the self," as Foucault called it: the technology of governing by persuading us to govern ourselves on behalf of the govenrment. This runs the gamut from early campaigns for improved personal hygiene, to the marketing of deodorants and toothpaste, to obsessive monitoring of what we consume and how we exercise, to therapy and Closure and self-fulfillment, to Identity Politics and Safe Zones - all things that, while often valuable in themselves, keep us focused on the cultivation of our own Self and out of the social arena in which we might challenge the governing regime. And, of course, keeps us continually consuming goods and services.

There's a lot more to the book, but I've blathered on, enough, I think.

The Agony of Eros by Byung-Chul Han, translated by Erik Butler. MIT Press.

The Quick Version

This is a really interesting book (and short - 56 pages!). Han, a Korean-German philosopher, advances the view that our modern "achievement society" is killing love. In a nutshell, his premise is that we are increasingly imprisoned in a culture of "positivity," encouraged to accumulate goods, accomplishments, experiences, and pleasures; this forecloses our availability to the "negation" required by love.

Han uses the terms "positive" and "negative" in a slightly non-standard way. The positive is the category of the countable, the visible, the accessible, or recognizable. The negative is the territory of the unknown, the risk, the loss. If love, as he claims, requires the willingness to surrender the Self to the unknowable Other, to be fully vulnerable to possibilities, then a devotion to positivity prevents us from ever making the journey from self to loss-of-self to a new, enriched self.

Further Commentary

Han is a German philosopher, so 56 pages takes longer to read than you might think. Still, he writes a very lucid prose - aside from some specialized terminology. His topic is Love, but he extends the analysis at points to Politics, Science, and Art. These four categories are taken from Alain Badiou, who designates them as the only four spheres in which a true Event can occur - Event being the irruption into the world of something previously impossible. For Badiou, the quintessential event is the Incarnation of Christ (surprisingly, perhaps, since Badiou is an atheist), but falling in love is the Event to which we all have access. For Badiou and Han, the only Well-lived life is one that exhibits faithfulness to an Event.

Anyway, Han's primary target is neoliberalism and its peripherals: first for its over-riding demand to consume and to accumulate; second for its intensification of a long-developing Western individualism that turns us ever more inward and brings us to look at others as mirrors (fun-house or otherwise) of ourselves. Implicated in this is intensifying "care of the self," as Foucault called it: the technology of governing by persuading us to govern ourselves on behalf of the govenrment. This runs the gamut from early campaigns for improved personal hygiene, to the marketing of deodorants and toothpaste, to obsessive monitoring of what we consume and how we exercise, to therapy and Closure and self-fulfillment, to Identity Politics and Safe Zones - all things that, while often valuable in themselves, keep us focused on the cultivation of our own Self and out of the social arena in which we might challenge the governing regime. And, of course, keeps us continually consuming goods and services.

There's a lot more to the book, but I've blathered on, enough, I think.

46Storeetllr

No, not nearly enough blathering, though much more about a 56-page book might be a bit much. I guess I'll just have to read the book. ;) Good review!

47majleavy

Thanks.

I think it bears on the conversation we had about when sex scenes in a book intrude or fit. Han is convinced that our culture of transparency, as he calls it, turns sex itself into pornography - the more we become dedicated to showing/telling, the more it becomes about mere display and less likely we become to offer ourselves to the unknown. He links this to a perceived stagnation in literature and art, but I haven't done the work of deciphering precisely how and of how it applies to representation of sexual encounters.

I think it bears on the conversation we had about when sex scenes in a book intrude or fit. Han is convinced that our culture of transparency, as he calls it, turns sex itself into pornography - the more we become dedicated to showing/telling, the more it becomes about mere display and less likely we become to offer ourselves to the unknown. He links this to a perceived stagnation in literature and art, but I haven't done the work of deciphering precisely how and of how it applies to representation of sexual encounters.

48Berly

Michael--Thanks for piping up on my thread. Welcome! And look at you, going gangbuster on the books and reviews! I'd say you've got the hang of it. ; )

49karenmarie

Hi Michael!

I’m a first time visitor and happy to be here.

Just a few thoughts:

>15 majleavy: Anyway, this is a book for anyone inclined to think that Trump supporters are, by definition, stupid, deluded, or despicable. It's a quick but careful analysis of how citizens of the "fly-over states" are driven by deep, serious, and honorable values, that we urban elites ignore, discount, or are just generally unaware of, at - as we saw in the past election -our own, and the nation's, peril. Williams counsels us all to start trying to understand each other, and stop the demonizing in which both "sides" are inclined to indulge.

I am reading a book called The Righteous Mind which posits the same basic thing, but breaking down morality into six moral foundations and discussing how individuals have internalized one or more and how they inform political and religious decisions.