Oct - Dec 2016: Dictators, Dictatorships and Other Forms of Tyranny

CharlasReading Globally

Únete a LibraryThing para publicar.

1SassyLassy

Welcome to Reading Globally's fourth quarter: Dictators, Dictatorships and Other Forms of Tyranny.

What are these things? The OED gives the following definitions:

Dictator

- a ruler with total power over a country, typically one who has obtained control by force

- a person who behaves in an autocratic way

- (in ancient Rome) a chief magistrate with absolute power, appointed in an emergency

Dictatorship

- government by a dictator

- a country governed by a dictator

- absolute authority in any sphere

Tyrant

- a cruel and oppressive ruler

- a person exercising power in a cruel, unreasonable or arbitrary way

- a ruler who seized absolute power without legal right

It may also be helpful to look at despots:

Despot

- a ruler or other person who holds absolute power; typically one who exercises it in a cruel or oppressive way

There seems to be a subtle difference between tyrants and despots in that the despot may have begun ruling with a legitimate claim to power, such as divine right.

What are these things? The OED gives the following definitions:

Dictator

- a ruler with total power over a country, typically one who has obtained control by force

- a person who behaves in an autocratic way

- (in ancient Rome) a chief magistrate with absolute power, appointed in an emergency

Dictatorship

- government by a dictator

- a country governed by a dictator

- absolute authority in any sphere

Tyrant

- a cruel and oppressive ruler

- a person exercising power in a cruel, unreasonable or arbitrary way

- a ruler who seized absolute power without legal right

It may also be helpful to look at despots:

Despot

- a ruler or other person who holds absolute power; typically one who exercises it in a cruel or oppressive way

There seems to be a subtle difference between tyrants and despots in that the despot may have begun ruling with a legitimate claim to power, such as divine right.

2SassyLassy

Who are these people?

Ask around for names of dictators and the top three will be some combination of Hitler, Stalin and Mao.

These were all twentieth century leaders. The twentieth century does seem to have a huge number with these easily joining the list:

Idi Amin Dada: Uganda

P W Botha: South Africa

Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi): Republic of China, first on the mainland and then in Taiwan

Francisco Franco: Spain

Enver Hoxha: Albania

Yahya Khan: Pakistan

Kim Jong-il: Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea)

Lenin

Robert Mugabe: Zimbabwe

Enver Pasha: Ottoman Empire

Augusto Pinochet: Chile

Josip Broz Tito: Yugoslavia

Others who operated on a more circumscribed stage would include:

Nicolae Ceausescu: Romania

Jean Claude Duvalier: Haiti

Daniel Ortega: Nicaragua

Muammer el-Qaddafi: Libya

Antonio Salazar: Portugal

Suharto: Indonesia

Then there were the grey faces in charge of so much of Eastern Europe post WWII, including:

Wladyslaw Gomulka: Poland

Erich Honecker: German Democratic Republic

There are many other names that could be added, but that would take up the whole topic. Today, Bashir al-Assad and Vladimir Putin easily fit in.

3SassyLassy

Looking back at the Oxford definition, dictators were originally "appointed in an emergency", suggesting some legitimate origin. Dictators still often achieve power through an electoral process, sometimes rigged, but the initial desire is to appear legitimate.

One of the first signs that a leader and country are heading toward a dictatorship is the suspension of elections. Existing civil liberties are suspended. The leader makes a move to gain absolute power through legal fraud, or a coup d'état. with a state of emergency being declared. This allows the dictator to rule by decree, having some legislative authority for his actions. Dictatorships may soon shed all pretence at legitimacy though, and the country is governed outside the rule of law. In other cases, sham parliaments or legislatures continue the illusion of governing.

Dictators often initially have supporters, especially if they have replaced another tyrant. Whether they have good initial support or not, a cult of personality may develop around them, often manufactured.

Tyrants from earlier days usually didn't have the bother of having to rationalize their rule to the people. Some came to the throne legitimately, some murdered their way there, but the requirement to prove you belonged was not a real concern. Others, like Leopold II of the Belgians, may have presented well at home, but ran their colonies like true autocrats.

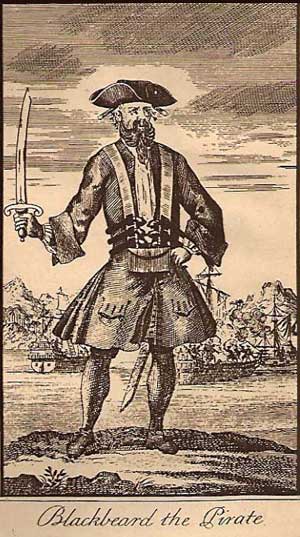

Some dictators did not even have countries to control. The Republic of Pirates held sway over the Caribbean in the early eighteenth century, fighting sovereign nations, establishing their own laws, and holding their own elections, but with a leader who was supreme. They were as feared as any land bound contemporaries.

4SassyLassy

Naturally writers have found endless material in all this.

Some writers remain in their own country, willingly or otherwise, while others write from exile. This naturally creates tension between the two camps, and differing views of the country for readers, depending on which writer they are reading. Some writers like Richard Rive of South Africa believed they could actually influence events at home.

Some long ago tyrants and despots are so intriguing that people are still writing about them today: subjects like Vlad III, Ivan the Terrible, or Tamerlane. Authors writing in protest may use these characters and tales of their acts of oppression as thinly disguised protest about a current leader. Ismail Kadare has used this technique, further distancing himself by setting the plot in another country.

Allegory is another way of writing of oppression. Perhaps the best known work here is George Orwell's attack on Stalin in Animal Farm, but there is also Ismail Kadare's The Seige.

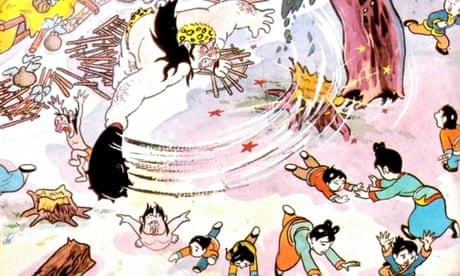

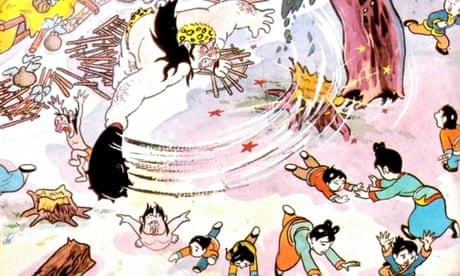

The memories of oppression don't end with the demise of a particular dictator. Thus, in the PRC, 1978-79 saw the rise of "scar literature" following the death of Mao in 1976. Scar literature "portrayed the personal suffering, wasted youth and talents, despair, fear, and paranoia everyone endured during the political persecution and 'class struggle' of the Cultural Revolution."*

Sometime tyrants just get tired. The Enchantress of Florence by Salman Rushdie features a worn out Akbar, leader of the Mughal Empire, along with that great critic of power, Niccolo Machiavelli.

In addition to fiction, there is a wealth of memoirs, diaries and letters by those who lived under dictatorships.

Lastly, dictators themselves often liked to see themselves as authors, some even saw themselves as poets or children's authors. Kim Jong-il, Mao, Hitler, Hoxha, Saddam Hussein, Mussolini and others have all left their thoughts on paper.

Boys Wipe out Bandits by Kim Jong-il, "The Power of Redemptive Violence"

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/13/north-korean-dictators-childrens-a...

______________

* https://www.mtholyoke.edu/~chen24r/classweb/wp/Postmao.html

Some writers remain in their own country, willingly or otherwise, while others write from exile. This naturally creates tension between the two camps, and differing views of the country for readers, depending on which writer they are reading. Some writers like Richard Rive of South Africa believed they could actually influence events at home.

Some long ago tyrants and despots are so intriguing that people are still writing about them today: subjects like Vlad III, Ivan the Terrible, or Tamerlane. Authors writing in protest may use these characters and tales of their acts of oppression as thinly disguised protest about a current leader. Ismail Kadare has used this technique, further distancing himself by setting the plot in another country.

Allegory is another way of writing of oppression. Perhaps the best known work here is George Orwell's attack on Stalin in Animal Farm, but there is also Ismail Kadare's The Seige.

The memories of oppression don't end with the demise of a particular dictator. Thus, in the PRC, 1978-79 saw the rise of "scar literature" following the death of Mao in 1976. Scar literature "portrayed the personal suffering, wasted youth and talents, despair, fear, and paranoia everyone endured during the political persecution and 'class struggle' of the Cultural Revolution."*

Sometime tyrants just get tired. The Enchantress of Florence by Salman Rushdie features a worn out Akbar, leader of the Mughal Empire, along with that great critic of power, Niccolo Machiavelli.

In addition to fiction, there is a wealth of memoirs, diaries and letters by those who lived under dictatorships.

Lastly, dictators themselves often liked to see themselves as authors, some even saw themselves as poets or children's authors. Kim Jong-il, Mao, Hitler, Hoxha, Saddam Hussein, Mussolini and others have all left their thoughts on paper.

Boys Wipe out Bandits by Kim Jong-il, "The Power of Redemptive Violence"

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/13/north-korean-dictators-childrens-a...

______________

* https://www.mtholyoke.edu/~chen24r/classweb/wp/Postmao.html

5SassyLassy

While dictators and despots are found all over the world, South and Central America have had so much experience with them that there is a whole fiction genre known as the dictator novel, with its origins in the nineteenth century. Its characteristics are:

- strong political themes

- an examination of power

- reflections on authoritarianism

Some of the best examples of this genre are:

The President by Miguel Angel Asturias of Guatemala, Nobel Prize winner 1967

- written in 1933, but not published until 1946 in Mexico, where it was released privately

- deals with the dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera

Reasons of State by Alejo Carpentier of Cuba

- 1974

- synthesis of various dictators, but Gerardo Machado of Cuba was the target

The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel Garcia Marquez of Columbia, Nobel Prize 1982

- 1975

- "a poem on the solitude of power"

- synthesis of various dictators such as Franco (Spain), Gustavo Rojas Penilla (Colombia), and Juan Vincente Gomez (Venezuela)

I, The Supreme by Augusto Roa Bastos of Paraguay

-1974

- account of the nineteenth century dictator José Gaspar Rodriguez de Francia

- Alfredo Stroessner was dictator of Paraguay at the time of publication and it is in part an attack on him

The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa of Peru, Nobel Prize winner 2010

- 2000

- a devastating portrayal of the regime of Rafael Léonidas Trujillo of the Dominican Republic, not for the faint of heart

- strong political themes

- an examination of power

- reflections on authoritarianism

Some of the best examples of this genre are:

The President by Miguel Angel Asturias of Guatemala, Nobel Prize winner 1967

- written in 1933, but not published until 1946 in Mexico, where it was released privately

- deals with the dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera

Reasons of State by Alejo Carpentier of Cuba

- 1974

- synthesis of various dictators, but Gerardo Machado of Cuba was the target

The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel Garcia Marquez of Columbia, Nobel Prize 1982

- 1975

- "a poem on the solitude of power"

- synthesis of various dictators such as Franco (Spain), Gustavo Rojas Penilla (Colombia), and Juan Vincente Gomez (Venezuela)

I, The Supreme by Augusto Roa Bastos of Paraguay

-1974

- account of the nineteenth century dictator José Gaspar Rodriguez de Francia

- Alfredo Stroessner was dictator of Paraguay at the time of publication and it is in part an attack on him

The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa of Peru, Nobel Prize winner 2010

- 2000

- a devastating portrayal of the regime of Rafael Léonidas Trujillo of the Dominican Republic, not for the faint of heart

6SassyLassy

Here are a few writers to start with:

Ismail Kadare of Albania

- this author would get my vote anytime for the Nobel Prize in Literature

- just about anything by him, but standouts for this theme would be The Siege, mentioned above, and The Concert, which gives the reader both Hoxha's Albania and Mao's China

Arthur Koestler 1905-1983, Hungary and UK

- somewhat out of favour nowadays, but wrote two great novels on totalitarianism:

-- Darkness at Noon (1940) about one person in Stalin's purges, and

-- Arrival and Departure (1943 about escape from a fascist regime

Tomas Eloy Martinez of Argentina, exiled in 1976 and went to Venezuela, then to the US (1884)

- his best known novels in English are The Péron Novel (1985) and Santa Evita (1995) about Eva Peron's corpse

Richard Rive 1931-1989 of South Africa

- wrote against apartheid and other forms of racism

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn 1918-2008, Russia/former Soviet Union- Nobel Prize 1970

- once, again, just about anything by this author, but Cancer Ward is a suggestion

__________________________________

Now for some titles

FICTION

Idi Amin

- The Last King of Scotland 1998 by Giles Foden: this was a title Amin actually gave himself

- Snakepit 2004 by Moses Isegawa

Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos

- Dogeaters 1990 by Jessica Hagedorn

Muammar el-Qaddafi

- In the Country of Men 2006 by Hisham Matar

Czech Republic

- The Engineer of Human Souls by Joseph Skvorecky 1984

NON FICTION

Albania

A Short Border Handbook by Gazmend Kapllani

Libya

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar

________________________________

OTHER SOURCES

- many of the titles from our last quarter would easily fit into this quarter's reading: http://www.librarything.com/topic/226285 Many of the earlier threads also have good suggestions

If you need help finding more dictators, here is a list of so called "friendly dictators" from the US State Department. The names and countries are misaligned, so that the name belongs to the country on the line below. http://www.progressivewritersbloc.com/DC/FriendlyDictators.htm

Ismail Kadare of Albania

- this author would get my vote anytime for the Nobel Prize in Literature

- just about anything by him, but standouts for this theme would be The Siege, mentioned above, and The Concert, which gives the reader both Hoxha's Albania and Mao's China

Arthur Koestler 1905-1983, Hungary and UK

- somewhat out of favour nowadays, but wrote two great novels on totalitarianism:

-- Darkness at Noon (1940) about one person in Stalin's purges, and

-- Arrival and Departure (1943 about escape from a fascist regime

Tomas Eloy Martinez of Argentina, exiled in 1976 and went to Venezuela, then to the US (1884)

- his best known novels in English are The Péron Novel (1985) and Santa Evita (1995) about Eva Peron's corpse

Richard Rive 1931-1989 of South Africa

- wrote against apartheid and other forms of racism

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn 1918-2008, Russia/former Soviet Union- Nobel Prize 1970

- once, again, just about anything by this author, but Cancer Ward is a suggestion

__________________________________

Now for some titles

FICTION

Idi Amin

- The Last King of Scotland 1998 by Giles Foden: this was a title Amin actually gave himself

- Snakepit 2004 by Moses Isegawa

Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos

- Dogeaters 1990 by Jessica Hagedorn

Muammar el-Qaddafi

- In the Country of Men 2006 by Hisham Matar

Czech Republic

- The Engineer of Human Souls by Joseph Skvorecky 1984

NON FICTION

Albania

A Short Border Handbook by Gazmend Kapllani

Libya

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar

________________________________

OTHER SOURCES

- many of the titles from our last quarter would easily fit into this quarter's reading: http://www.librarything.com/topic/226285 Many of the earlier threads also have good suggestions

If you need help finding more dictators, here is a list of so called "friendly dictators" from the US State Department. The names and countries are misaligned, so that the name belongs to the country on the line below. http://www.progressivewritersbloc.com/DC/FriendlyDictators.htm

7SassyLassy

Here are some questions to think about as you read:

- Is the writer in exile or not? How does that affect the writing?

- What were the writer's political affiliations at the time of writing, voluntary or otherwise? Have they changed over time?

- If this is not a current book, has the country changed its attitude to either the writer or the particular book in the meantime?

- How does the writer deal with the topic (magic realism, allegory, straightforward narration, different time or place, etc)?

Most important of all:

These are just a few suggestions to introduce the topic. What will you be reading?

- Is the writer in exile or not? How does that affect the writing?

- What were the writer's political affiliations at the time of writing, voluntary or otherwise? Have they changed over time?

- If this is not a current book, has the country changed its attitude to either the writer or the particular book in the meantime?

- How does the writer deal with the topic (magic realism, allegory, straightforward narration, different time or place, etc)?

Most important of all:

These are just a few suggestions to introduce the topic. What will you be reading?

8LolaWalser

I think I'll opt for "other forms of tyranny"--something that throws light on the capitalist neoliberal stranglehold on the world, disguised as "freedom" and "democracy" even as it ushers in the apocalypse.

9ELiz_M

Novels about Rafael Léonidas Trujillo or set during his reign:

Before we were free by Julia Alvarez

The Farming of Bones by Edwidge Danticat

Galíndez by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán

Novels about Augusto Pinochet or set during his reign:

The Days of the Rainbow by Antonio Skármeta

Prisoner Without A Name, Cell Without a Number by Jacobo Timerman

The News from Paraguay by Lily Tuck

The Case of Comrade Tulayev by Victor Serge

Random other novels:

The Coup by John Updike

King of Cuba by Cristina Garcia

Tyrant Banderas by Ramon Del Valle-Inclan

1984 by George Orwell

Bend Sinister by Vladimir Nabokov

It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis

A Case of Exploding Mangoes by Mohammed Hanif

The Orphan Master's Son by Adam Johnson

ETA: Some of the above are completely fictional -- not based on real people/historical events. Not sure if they are included in the theme....

Before we were free by Julia Alvarez

The Farming of Bones by Edwidge Danticat

Galíndez by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán

Novels about Augusto Pinochet or set during his reign:

The Days of the Rainbow by Antonio Skármeta

Prisoner Without A Name, Cell Without a Number by Jacobo Timerman

The News from Paraguay by Lily Tuck

The Case of Comrade Tulayev by Victor Serge

Random other novels:

The Coup by John Updike

King of Cuba by Cristina Garcia

Tyrant Banderas by Ramon Del Valle-Inclan

1984 by George Orwell

Bend Sinister by Vladimir Nabokov

It Can't Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis

A Case of Exploding Mangoes by Mohammed Hanif

The Orphan Master's Son by Adam Johnson

ETA: Some of the above are completely fictional -- not based on real people/historical events. Not sure if they are included in the theme....

10thorold

Quite a lot of the books I've been reading over the past couple of years have some bearing on oppressive regimes of one sort or another - Haiti, East Germany, revolutionary France, tsarist Russia, Cuba...

To avoid making an endless list I'll try to pick out a few that especially struck me:

- Herztier (The land of green plums) by Herta Müller - Romania, one of the most vivid accounts I've read of what living under an authoritarian regime does to your mind

- Er ist wieder da (Look who's back) by Timur Vermes - (Hitler) clever satire of how populists get to become dictators, but in the worst possible taste, so I wouldn't really recommend it

- Anatomía de un instante (The anatomy of a moment) by Javier Cercas - (Spain) - fascinating "non-fiction novel" about the the attempted coup of 1981

- Sostiene Pereira (Pereira declares) by Antonio Tabucchi - (Portugal) - another one about psychological effects of living under dictatorship

- Nada by Carmen Laforet - similar, but for Barcelona shortly after the civil war

- La chartreuse de Parme by Stendhal - destructive analysis of absolutism in a small Italian state after 1815

...and one I read last week

- Stille Zeile sechs by Monika Maron - a close look at one of the people who ran the DDR in old age

To avoid making an endless list I'll try to pick out a few that especially struck me:

- Herztier (The land of green plums) by Herta Müller - Romania, one of the most vivid accounts I've read of what living under an authoritarian regime does to your mind

- Er ist wieder da (Look who's back) by Timur Vermes - (Hitler) clever satire of how populists get to become dictators, but in the worst possible taste, so I wouldn't really recommend it

- Anatomía de un instante (The anatomy of a moment) by Javier Cercas - (Spain) - fascinating "non-fiction novel" about the the attempted coup of 1981

- Sostiene Pereira (Pereira declares) by Antonio Tabucchi - (Portugal) - another one about psychological effects of living under dictatorship

- Nada by Carmen Laforet - similar, but for Barcelona shortly after the civil war

- La chartreuse de Parme by Stendhal - destructive analysis of absolutism in a small Italian state after 1815

...and one I read last week

- Stille Zeile sechs by Monika Maron - a close look at one of the people who ran the DDR in old age

11thorold

As everyone knows, I'm addicted to tagmashes:

dictators, fiction: http://www.librarything.com/tag/dictators,+fiction

Top hit is The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Achebe's Anthills of the savannah and Wizard of the Crow by Ngugi wa'Thiong'o are two African books not mentioned here yet, most of the rest are familiar.

dictatorship, fiction: http://www.librarything.com/tag/dictatorship,+fiction

- more or less the same in a different order. One I'd forgotten about is Night train to Lisbon by the Swiss author Pascal Mercier (Salazar again).

dictators, fiction: http://www.librarything.com/tag/dictators,+fiction

Top hit is The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz

Achebe's Anthills of the savannah and Wizard of the Crow by Ngugi wa'Thiong'o are two African books not mentioned here yet, most of the rest are familiar.

dictatorship, fiction: http://www.librarything.com/tag/dictatorship,+fiction

- more or less the same in a different order. One I'd forgotten about is Night train to Lisbon by the Swiss author Pascal Mercier (Salazar again).

12SassyLassy

>8 LolaWalser: Looking forward to the suggested reading list!

>9 ELiz_M: Fictional dictators are fine. They are often used to shed light on the real life kind.

>10 thorold: The Maron and Stendhal are on my TBR (Maron partially read), so good places to start.

>11 thorold: Thank you and LT for the great tagmashes. There's a world of reading right there.

>9 ELiz_M: Fictional dictators are fine. They are often used to shed light on the real life kind.

>10 thorold: The Maron and Stendhal are on my TBR (Maron partially read), so good places to start.

>11 thorold: Thank you and LT for the great tagmashes. There's a world of reading right there.

13LolaWalser

>12 SassyLassy:

It begins with The Communist Manifesto and ends with all of Chomsky and Naomi Klein. :)

(Some) reasons why we're still waiting for contemporary fictional reckonings:

We Are All Neoliberals Now: The New Genre of Plastic Realism in American Fiction

It begins with The Communist Manifesto and ends with all of Chomsky and Naomi Klein. :)

(Some) reasons why we're still waiting for contemporary fictional reckonings:

We Are All Neoliberals Now: The New Genre of Plastic Realism in American Fiction

14lriley

The Pinochet dictatorship led to a number of other dictatorships throughout South and Central America. The United States helped bring some of these about particularly during the Nixon/Ford--Reagan years. The School of the Americas at Fort Benning Ga. trained police and military personnel from many of these countries in suppression and torture techniques. None of this is controversial because it's proven fact. We can even give that training school credit for creating the Mexican drug cartel the Zetas.

Speaking of neoliberal economics Pinochet's Chile was the laboratory for Milton Friedman and his Chicago boys to test out their economic theories. A few years after the Chilean coup Argentina had his own coup and subsequent military dictatorship under a triumvirate of military leaders--Gen. Videla (representing the Army) Adm. Massera (representing the Navy) and Gen. Agosti (representing the Air Force). On the one year anniversary of their taking control the investigative journalist and true crime writer Rodolfo Walsh wrote his Open letter to the military junta--describing and detailing their atrocities galore. For anyone interested that can be easily found on the internet. Walsh described the censorship of the press, the subversion of rules of the law and the courts including the suspension habeas corpus, the destruction of the unions, the thousands of murders and disappearances, the fear of the population. He even describes the death of his daughter. To Walsh though the worst he saved for last. Argentina having borrowed and modeled itself on the Pinochet regime also became another nation advocating neoliberal economic programs to which Walsh accused the government of waging economic warfare against its own population. The truth is the military had no idea how to run a government and had no idea what society meant. (Well Thatcher didn't either). So they created a corrupt mess and enriched and engorged themselves on their people's misery and tore their country apart. On the day that Walsh mailed his open letter to news organizations around the world he was later accosted on the streets of Buenos Aires by armed Navy officers. Walsh was armed too and defended himself. He was last seen gravely wounded being thrown into the trunk of a Ford Cortina. The speculation was his body was later incinerated at the School of Naval Mechanics otherwise knows as ESMA.

Speaking of neoliberal economics Pinochet's Chile was the laboratory for Milton Friedman and his Chicago boys to test out their economic theories. A few years after the Chilean coup Argentina had his own coup and subsequent military dictatorship under a triumvirate of military leaders--Gen. Videla (representing the Army) Adm. Massera (representing the Navy) and Gen. Agosti (representing the Air Force). On the one year anniversary of their taking control the investigative journalist and true crime writer Rodolfo Walsh wrote his Open letter to the military junta--describing and detailing their atrocities galore. For anyone interested that can be easily found on the internet. Walsh described the censorship of the press, the subversion of rules of the law and the courts including the suspension habeas corpus, the destruction of the unions, the thousands of murders and disappearances, the fear of the population. He even describes the death of his daughter. To Walsh though the worst he saved for last. Argentina having borrowed and modeled itself on the Pinochet regime also became another nation advocating neoliberal economic programs to which Walsh accused the government of waging economic warfare against its own population. The truth is the military had no idea how to run a government and had no idea what society meant. (Well Thatcher didn't either). So they created a corrupt mess and enriched and engorged themselves on their people's misery and tore their country apart. On the day that Walsh mailed his open letter to news organizations around the world he was later accosted on the streets of Buenos Aires by armed Navy officers. Walsh was armed too and defended himself. He was last seen gravely wounded being thrown into the trunk of a Ford Cortina. The speculation was his body was later incinerated at the School of Naval Mechanics otherwise knows as ESMA.

15RidgewayGirl

>8 LolaWalser: Capital by John Lanchester?

>9 ELiz_M: Needless pedantry: The News from Paraguay by Lily Tuck is not about Pinochet, but a much earlier (mid-1850s) Paraguayan dictator, Franco Lopez.

Plenty to choose from here. I'll have to take a closer look at my shelves and decide what direction I'd like to go.

>9 ELiz_M: Needless pedantry: The News from Paraguay by Lily Tuck is not about Pinochet, but a much earlier (mid-1850s) Paraguayan dictator, Franco Lopez.

Plenty to choose from here. I'll have to take a closer look at my shelves and decide what direction I'd like to go.

16ELiz_M

>15 RidgewayGirl: Right. The space was supposed to indicate it was a new topic (I thought I would find more books, but got called away from the post). Clearly I need to add a few more headers.

17LolaWalser

>15 RidgewayGirl:

Thanks for the suggestion--not for me, though, I disliked a book of his I read, Debt to pleasure.

Thanks for the suggestion--not for me, though, I disliked a book of his I read, Debt to pleasure.

18rocketjk

I just finished the first two books of British writer Richard Hughes' "The Human Predicament" Trilogy, The Fox in the Attic and The Wooden Shepherdess. (Hughes died before finishing the third novel.) I bring them up here because, among two or three main plot threads, Hughes presented an in-depth fictionalized view of the early days of the Nazi Party, including Hitler's many stratagems in maintaining and consolidating his hold over the movement and in patiently taking advantage of his opportunities when they arose. The first book takes the reader through Hitler's first attempt to seize power, the Beer Hall Putsch, and the second concludes with newly elected Chancellor Hitler's brutal internal (and external) purge of potential (or imagined) rivals to his party dominance, known as the Night of the Long Knives. Hughes the afterwords to both books claimed to have done intensive research into such Nazi party records as still existed and into letters and diaries in order to recreate the most realistic version possible. Of course, I have no idea as to the validity of that claim. The books are uneven, but that aspect of them, I thought, was worth noting here.

19thorold

Slightly tangential to the main topic, I've been diverted by Volker Weidermann's Ostende 1936 into exploring a few writers whose works were banned by the Nazis. The content of the books by Zweig and Roth I've (re-)read so far doesn't really have any direct relevance to the topic of dictatorship, although the fact of their banning does, of course; one interesting comment Weidermann makes is that the writers exiled from Germany in the thirties mostly avoided writing about current events because they didn't have first-hand experience, and went over to historical topics. It looks as though Irmgard Keun might be an exception to that rule, but I haven't got to her later books yet.

20lriley

#19---Alfred Doblin is a favorite of mine and was one of the writers banned by the Nazis and forced into exile.

21thorold

>20 lriley: Definitely!

On another note, I've just picked up a copy of Yo el supremo from the Spanish shelf of the charity shop. Looks seriously intimidating - 90 pages of critical introduction followed by 500 pages of heavily-footnoted small print. I suspect it's going to stay on the TBR shelf for a little while...

On another note, I've just picked up a copy of Yo el supremo from the Spanish shelf of the charity shop. Looks seriously intimidating - 90 pages of critical introduction followed by 500 pages of heavily-footnoted small print. I suspect it's going to stay on the TBR shelf for a little while...

23mabith

I highly recommend Ismail Kadare's The Siege, really really great read.

24spiphany

>11 thorold: Wizard of the Crow is great! I was going to recommend it for this quarter's theme read. It's also a surprisingly hopeful and playful novel, given the topic.

I've just been reading a text by a rather forgotten author, Reinhard Lettau, called Frühstücksgespräche in Miami (Breakfast Conversations in Miami), featuring Latin American dictators (current and former) gathered in a Florida hotel. I read this in German; an English translation seems to exist, but I don't know how difficult it would be to track down.

The dictators' discussion topics include the optimal number of deputy presidents, the political value of ugliness, why abdicating is a useful (albeit risky) strategy, the problems of arranging earthquakes in the hopes of benefiting from international aid ("all I ever got were airplanes loads of wool blankets and powdered milk") and much more. Lettau's satirical barbs are not only directed against the absurd posturing of these petty dicators, but also against American interference in Latin America. The piece was written in the 1970s; Lettau, who spent most of his adult life in the US, also published nonfiction reflections entitled Täglicher Faschismus (Daily Fascism) criticizing American politics and society in this period.

Some highlights of the text (which is structured loosely as a play and has been adapted for performance as such):

- You are the dictator before the previous one, are you not?

- No, I'm the final one.

- Are you sure?

- I can't be completely certain of course. One can't always be watching the borders.

- How long were you a dicator then?

(The addressee casts his eyes downwards.)

- Your dictatorship lasted only a day, that's right; strictly speaking you only represented a transitional government. Therefore you can't have anything to say here!

- Listening to you, one could get the impression that in our countries we are not the ones exercising power, but rather the businessmen. In my entire life I have never exchanged a single word with a business leader. Besides, I prefer the company of real men. Whenever anyone came to see me and started on about economic questions or money, I gave him a kick in the rear. We're not Marxists, after all; they also talk incessantly about money. ... The books of both Marxists and industrialists are full of numbers. The one groups counts their own profits, the other group counts the profits of others. I am given the choice between greed and jealousy, and the real questions facing humanity are forgotten.

- I had a policy of censorship, but nobody noticed because it wasn't reported in the newspaper. It wouldn't be news after all, if one were to insert an announcement in the newspaper: "Today there is still censorship!" One could just as well write headlines like: "Today is another day!"

- In Russia there are headlines like that. Once I read the following headline there: "In the past week many saucepans were manufactured!"

- Great headline! One doesn't forget something like that!

- As a dictator one remains an eternal child. Childhood is an early form of dictatorship. At any rate, I maintained a certain childlikeness as a dictator. Do you have an objection to children? They're our most precious resource! Children are the future! And you're not going to speak against the future, are you?

-----

While researching more about Lettau, I stumbled across another rather obscure piece that might be of interest, although it's actually as much an audio piece as it is a written work: Mauricio Kagel's radio play "Der Tribun" (not available in English, as far as I know). He took the language of political speeches and condensed it into a collection of typical phrases, which is then integrated into an audio performance with military musik, the sounds of marching, loudspeaker announcements and shouts from the public.

There are some performances of this online, although I hesitate to provide any links since I'm not sure if all of them respect copyright. It's quite effective, albeit quite difficult to listen to for very long because of the sense of revulsion that it evokes.

I've just been reading a text by a rather forgotten author, Reinhard Lettau, called Frühstücksgespräche in Miami (Breakfast Conversations in Miami), featuring Latin American dictators (current and former) gathered in a Florida hotel. I read this in German; an English translation seems to exist, but I don't know how difficult it would be to track down.

The dictators' discussion topics include the optimal number of deputy presidents, the political value of ugliness, why abdicating is a useful (albeit risky) strategy, the problems of arranging earthquakes in the hopes of benefiting from international aid ("all I ever got were airplanes loads of wool blankets and powdered milk") and much more. Lettau's satirical barbs are not only directed against the absurd posturing of these petty dicators, but also against American interference in Latin America. The piece was written in the 1970s; Lettau, who spent most of his adult life in the US, also published nonfiction reflections entitled Täglicher Faschismus (Daily Fascism) criticizing American politics and society in this period.

Some highlights of the text (which is structured loosely as a play and has been adapted for performance as such):

- You are the dictator before the previous one, are you not?

- No, I'm the final one.

- Are you sure?

- I can't be completely certain of course. One can't always be watching the borders.

- How long were you a dicator then?

(The addressee casts his eyes downwards.)

- Your dictatorship lasted only a day, that's right; strictly speaking you only represented a transitional government. Therefore you can't have anything to say here!

- Listening to you, one could get the impression that in our countries we are not the ones exercising power, but rather the businessmen. In my entire life I have never exchanged a single word with a business leader. Besides, I prefer the company of real men. Whenever anyone came to see me and started on about economic questions or money, I gave him a kick in the rear. We're not Marxists, after all; they also talk incessantly about money. ... The books of both Marxists and industrialists are full of numbers. The one groups counts their own profits, the other group counts the profits of others. I am given the choice between greed and jealousy, and the real questions facing humanity are forgotten.

- I had a policy of censorship, but nobody noticed because it wasn't reported in the newspaper. It wouldn't be news after all, if one were to insert an announcement in the newspaper: "Today there is still censorship!" One could just as well write headlines like: "Today is another day!"

- In Russia there are headlines like that. Once I read the following headline there: "In the past week many saucepans were manufactured!"

- Great headline! One doesn't forget something like that!

- As a dictator one remains an eternal child. Childhood is an early form of dictatorship. At any rate, I maintained a certain childlikeness as a dictator. Do you have an objection to children? They're our most precious resource! Children are the future! And you're not going to speak against the future, are you?

-----

While researching more about Lettau, I stumbled across another rather obscure piece that might be of interest, although it's actually as much an audio piece as it is a written work: Mauricio Kagel's radio play "Der Tribun" (not available in English, as far as I know). He took the language of political speeches and condensed it into a collection of typical phrases, which is then integrated into an audio performance with military musik, the sounds of marching, loudspeaker announcements and shouts from the public.

There are some performances of this online, although I hesitate to provide any links since I'm not sure if all of them respect copyright. It's quite effective, albeit quite difficult to listen to for very long because of the sense of revulsion that it evokes.

25thorold

>19 thorold: The second of Irmgard Keun's books that I've read turns out to be very relevant to this topic. The review below is cross-posted from my CR thread:

Nach Mitternacht (1937; After Midnight) by Irmgard Keun (Germany, 1905-1982)

Nach Mitternacht was Keun's fourth novel, her second to be published in Amsterdam after the Nazis banned her books in Germany, and the first she wrote in exile.

Sanna, the 19-year-old narrator, is an unremarkably, sane, prudent, young woman whose modest, conventional aims in life - to marry her boyfriend and set up in business with him in a small shop - are clearly not going to work out the way she hoped, as the world they live in seems to have gone mad around them. The action of the book takes place in Frankfurt over two days in 1936, with a series of scenes set in various prominent Frankfurt drinking-establishments and at a private party. (Maybe the extreme booziness of this novel has something to do with the collaboration with her lover Joseph Roth?) Hitler himself makes a brief cameo appearance, as his motorcade arrives at the opera house for him to give a speech, and Sanna watches him from a balcony of the pub.

The main aim of the book seems to be to explain and to satirise the effect of the Nazi dictatorship on ordinary Germans. There is a lot about the absurdities of the racial laws, the climate of fear and the enthusiastic way ordinary people took to the possibilities of denunciation (of neighbours, annoying family-members, business rivals...), the suppression of open criticism that left everyone bubbling over with dangerous political jokes they could hardly resist sharing, the suppression of any literature except uplifting Heimat-fiction and odes to the Führer, etc.

Tellingly, Sanna's drinking companion, the cynical journalist Heini, tells her that there's no point in literature in an authoritarian society. By definition, everything the authorities do is perfect, so there's no reason to write about it, any more than you would want to write articles about the sizes of wings the angels are wearing this year if you were in Paradise...

As we would expect, there are plenty of jokes, but also plenty that is very black indeed. In the final chapters we meet three British journalists who have come to Germany for a couple of days to interview Sanna's brother, a novelist who has tried to accommodate himself to the new régime. Their brief experience has left them impressed with how hospitable, cheerful and optimistic their German hosts are under their new leaders: Keun is making very sure that the reader won't fall into the same error. And we don't.

As a novel, it's a quick and lively read: Keun was a pro, and she knew she had something important to say and had a clear idea how to say it. Factually, it probably doesn't tell you anything about Nazi society that isn't in all the history books, but that's not really the point. There are very few direct contemporary accounts like this of what it felt like to be living in Nazi Germany as a German, written whilst it was still going on. Keun had only been away for a few months when she wrote this, and there are lots of really telling little details that stop you and make you think about things in a new way.

Nach Mitternacht (1937; After Midnight) by Irmgard Keun (Germany, 1905-1982)

Nach Mitternacht was Keun's fourth novel, her second to be published in Amsterdam after the Nazis banned her books in Germany, and the first she wrote in exile.

Sanna, the 19-year-old narrator, is an unremarkably, sane, prudent, young woman whose modest, conventional aims in life - to marry her boyfriend and set up in business with him in a small shop - are clearly not going to work out the way she hoped, as the world they live in seems to have gone mad around them. The action of the book takes place in Frankfurt over two days in 1936, with a series of scenes set in various prominent Frankfurt drinking-establishments and at a private party. (Maybe the extreme booziness of this novel has something to do with the collaboration with her lover Joseph Roth?) Hitler himself makes a brief cameo appearance, as his motorcade arrives at the opera house for him to give a speech, and Sanna watches him from a balcony of the pub.

The main aim of the book seems to be to explain and to satirise the effect of the Nazi dictatorship on ordinary Germans. There is a lot about the absurdities of the racial laws, the climate of fear and the enthusiastic way ordinary people took to the possibilities of denunciation (of neighbours, annoying family-members, business rivals...), the suppression of open criticism that left everyone bubbling over with dangerous political jokes they could hardly resist sharing, the suppression of any literature except uplifting Heimat-fiction and odes to the Führer, etc.

Tellingly, Sanna's drinking companion, the cynical journalist Heini, tells her that there's no point in literature in an authoritarian society. By definition, everything the authorities do is perfect, so there's no reason to write about it, any more than you would want to write articles about the sizes of wings the angels are wearing this year if you were in Paradise...

As we would expect, there are plenty of jokes, but also plenty that is very black indeed. In the final chapters we meet three British journalists who have come to Germany for a couple of days to interview Sanna's brother, a novelist who has tried to accommodate himself to the new régime. Their brief experience has left them impressed with how hospitable, cheerful and optimistic their German hosts are under their new leaders: Keun is making very sure that the reader won't fall into the same error. And we don't.

As a novel, it's a quick and lively read: Keun was a pro, and she knew she had something important to say and had a clear idea how to say it. Factually, it probably doesn't tell you anything about Nazi society that isn't in all the history books, but that's not really the point. There are very few direct contemporary accounts like this of what it felt like to be living in Nazi Germany as a German, written whilst it was still going on. Keun had only been away for a few months when she wrote this, and there are lots of really telling little details that stop you and make you think about things in a new way.

26SassyLassy

This was a book I read last year for my alphabet of authors in translation, but since it has not one but two dictators plus a contender, I thought I would add it in here:

The Concert by Ismail Kadare, this 1994 translation from the French by Barbara Bray from the translation from Albanian into French by Jusuf Vrioni

first published as Koncert në fund të dimrit in 1988

Despite its title, The Concert requires no real knowledge of music. What it does require is an interest in Sino-Albanian politics and a fascination with the final hours of Lin Biao. Certainly not a novel for everyone, but definitely one for me.

As negotiations for the Sino American rapprochement were going on, Gjerj Dibra flew to Beijing to deliver a letter from the Albanians, asking that the meeting with the American president be cancelled. Who was little Albania to demand such a thing? China's only ally, a tiny country cut off from the Europe which should have been its natural home dared defy Chairman Mao. Back in Tirana, Chinese diplomats, engineers, scientists, workers and trade delegations were disappearing from Albania as if they had never arrived, abandoning engineering projects, construction sites and trade missions.

This wouldn't be a Kadare book though without elements of the surreal. One nameless man, high in the Arctic, constantly sifts through transmissions in the ether, reading the tea leaves of changes in the rankings of the Chinese Politbureau. Mao Zedong wanders in and out of lucidity in his favourite cave retreat. The x-ray of the broken foot of a Chinese diplomat causes a rift between the two countries.

All these elements are essentially shadows, glimpses of greater realities. It is in this contrast between the world of conjecture and the harsh reality of Enver Hoxha's Albania that Kadare excels, setting up a real and justified paranoia. There are repeated references to MacBeth (was it because Mao and Lin Biao "were both hatching a plot based on treachery at a banquet?"), ghosts and isolation. Alone in China, Albanian Party member Skënder Berema repeatedly works out scenarios for Lin Biao's flight and death.

Finally there is the concert itself. Zhou Enlai had said the way to understand Chinese politics was to study Chinese theatre. Eleven hundred people, including Berema, received invitations on the very day of the concert.

Zhou Enlai, the man who knew all and controlled all, was contemplating his masks.

As the high level audience assembled, speculation ran rife.What was the plot of the performance? Were the movements of the second female dancer going to signify anything? Where and with whom was everyone seated? Hua Guofeng was working on his best imitation of Mao's hair to impress the audience. Finally all were assembled. Tensions built throughout the concert. The end of the performance brought a completely unexpected panic.

Kadare shifts events somewhat and timelines are unclear. Mao may die before Zhou, or the deaths may be the same day. The magic realism he employs, the varying iterations of the same story be it the massacre of Albanians in Kosovo, the war in Cambodia, or the leitmotif of the death of Lin Biao, illustrate the many forms history can take, and the impossibility of knowing the truth. This is classic Kadare.

___________

edited to correct touchstone which bizarrely yielded A Christmas Carol.

The Concert by Ismail Kadare, this 1994 translation from the French by Barbara Bray from the translation from Albanian into French by Jusuf Vrioni

first published as Koncert në fund të dimrit in 1988

Despite its title, The Concert requires no real knowledge of music. What it does require is an interest in Sino-Albanian politics and a fascination with the final hours of Lin Biao. Certainly not a novel for everyone, but definitely one for me.

As negotiations for the Sino American rapprochement were going on, Gjerj Dibra flew to Beijing to deliver a letter from the Albanians, asking that the meeting with the American president be cancelled. Who was little Albania to demand such a thing? China's only ally, a tiny country cut off from the Europe which should have been its natural home dared defy Chairman Mao. Back in Tirana, Chinese diplomats, engineers, scientists, workers and trade delegations were disappearing from Albania as if they had never arrived, abandoning engineering projects, construction sites and trade missions.

This wouldn't be a Kadare book though without elements of the surreal. One nameless man, high in the Arctic, constantly sifts through transmissions in the ether, reading the tea leaves of changes in the rankings of the Chinese Politbureau. Mao Zedong wanders in and out of lucidity in his favourite cave retreat. The x-ray of the broken foot of a Chinese diplomat causes a rift between the two countries.

All these elements are essentially shadows, glimpses of greater realities. It is in this contrast between the world of conjecture and the harsh reality of Enver Hoxha's Albania that Kadare excels, setting up a real and justified paranoia. There are repeated references to MacBeth (was it because Mao and Lin Biao "were both hatching a plot based on treachery at a banquet?"), ghosts and isolation. Alone in China, Albanian Party member Skënder Berema repeatedly works out scenarios for Lin Biao's flight and death.

Finally there is the concert itself. Zhou Enlai had said the way to understand Chinese politics was to study Chinese theatre. Eleven hundred people, including Berema, received invitations on the very day of the concert.

Zhou Enlai, the man who knew all and controlled all, was contemplating his masks.

He had three masks: the mask of a leader, the mask of one who obeys, and the mask as cold as ice. The first two he usually wore to government and Politbureau meetings or committees. The third he kept for occasions when he had to appear in public.

The clock on the wall behind him struck six. This was the first time he had gone out without one of his three masks. They were all out of date now. Instead he now wore a fourth. A death mask.

As the high level audience assembled, speculation ran rife.What was the plot of the performance? Were the movements of the second female dancer going to signify anything? Where and with whom was everyone seated? Hua Guofeng was working on his best imitation of Mao's hair to impress the audience. Finally all were assembled. Tensions built throughout the concert. The end of the performance brought a completely unexpected panic.

Kadare shifts events somewhat and timelines are unclear. Mao may die before Zhou, or the deaths may be the same day. The magic realism he employs, the varying iterations of the same story be it the massacre of Albanians in Kosovo, the war in Cambodia, or the leitmotif of the death of Lin Biao, illustrate the many forms history can take, and the impossibility of knowing the truth. This is classic Kadare.

___________

edited to correct touchstone which bizarrely yielded A Christmas Carol.

27SassyLassy

And just because I love Chinese posters, I thought I would add this which ties in with the book above:

Chinese Posters.net tells me that the script says "Long live the friendship of the parties of China and Albania, 1969"

They cite the source as Elez Biberaj: Albania and China - A Study of an Unequal Alliance.

Chinese Posters.net tells me that the script says "Long live the friendship of the parties of China and Albania, 1969"

They cite the source as Elez Biberaj: Albania and China - A Study of an Unequal Alliance.

28chlorine

Thanks a lot for the excellent introduction, SassyLassy!

I happen to have in my TBR Piégés par Staline (trapped by Stalin), by Nicolas Jallot. It's a non-fiction book about how Stalin offered to the Russians who had fled to France during the revolution, and their families, to come back to the USSR.

Officially they would live as first grade citizens, with nice jobs, and there was a lot of propaganda about how life in the USSR was wonderful. In practice they arrived during a famine, their papers were confiscated and they had to provide for themselves as well as they could, isolated as they were from the network of help of people who had never left and treated them as parias. This resulted in the death of the vast majority of these people.

Although it's non-fiction I'll start with this book, then try to read a novel fitting the theme. Ismail Kadare seems very interesting.

BTW earlier this year I've read The dream of the Celt by Mario Vargas Llosa, which is a novel about a historic character who denounced the way Leopold II dealt with the people in Belgium Congo (the book is more complex than that as it also addresses the question of the decolonisation of Ireland by Great Britain, before most of Ireland was an independent country, in a thought provoking way). Highly recommended.

I happen to have in my TBR Piégés par Staline (trapped by Stalin), by Nicolas Jallot. It's a non-fiction book about how Stalin offered to the Russians who had fled to France during the revolution, and their families, to come back to the USSR.

Officially they would live as first grade citizens, with nice jobs, and there was a lot of propaganda about how life in the USSR was wonderful. In practice they arrived during a famine, their papers were confiscated and they had to provide for themselves as well as they could, isolated as they were from the network of help of people who had never left and treated them as parias. This resulted in the death of the vast majority of these people.

Although it's non-fiction I'll start with this book, then try to read a novel fitting the theme. Ismail Kadare seems very interesting.

BTW earlier this year I've read The dream of the Celt by Mario Vargas Llosa, which is a novel about a historic character who denounced the way Leopold II dealt with the people in Belgium Congo (the book is more complex than that as it also addresses the question of the decolonisation of Ireland by Great Britain, before most of Ireland was an independent country, in a thought provoking way). Highly recommended.

29thorold

>28 chlorine: Your mention of Piégés par Staline makes me think of Sous lénine; notes d'une femme déportée en Russie par les Anglais by Odette Keun, which I read a few years ago. For reasons too complicated to go into, Ms Keun (a journalist and a Dutch citizen, but no relation to Irmgard Keun as far as I know) found herself in Odessa without any papers, and she describes travelling through Russia in the immediate aftermath of the revolution and civil war as a "guest" of the Cheka. Well-meant, but at times it reads a bit like Evelyn Waugh's version of Red Cavalry...

30chlorine

>29 thorold: I had never heard of Odette Keun or Evelyn Waugh (I'm quite surprised that Evelyn seems to be a male name btw), but from what I understand Piégés par Staline and Sous Lénine seem to be quite different. :)

31thorold

>30 chlorine: It was just the resonance of the French titles that struck me. No important reason why anyone should have heard of Odette Keun - the only other thing she's known for is having been H.G. Wells's mistress, a distinction she had to share with many other women of her generation... The gender-fluidity of English given names is probably no worse than that of French ones, but possibly more vulnerable to quirks of fashion.

32berthirsch

Trujillo of Dominican Republic

sections of Junot Diaz The Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

The dictatorships in Argentina

The Peron Novel and Purgatory by Tomas Eloy Martinez

Nathan Englander- The Ministry of Special Cases

All are excellent

sections of Junot Diaz The Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

The dictatorships in Argentina

The Peron Novel and Purgatory by Tomas Eloy Martinez

Nathan Englander- The Ministry of Special Cases

All are excellent

33berthirsch

Feast of the Goat-Dominican Republic.

Llosa on dictatorships:

http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/243291/vargas-llosa-on-defeating-dictators-with-li...

Llosa on dictatorships:

http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/243291/vargas-llosa-on-defeating-dictators-with-li...

34spiphany

I don't know how much politics are wanted here, so I'm going to phrase this obscurely (and would be happy to delete if deemed inappropriate): I'm finding that this theme read is touching just a bit too close to home at the moment.

I think I'm going to have to go in search of encouraging stories about resistance to oppression, or else join >8 LolaWalser: and creatively reinterpret the theme.

Bakhtin's writing on the carnavalesque feels like it might be worth revisiting. And the second part of Andrei Sinyavsky's Ivan the Fool has some encouraging things to say about the ability of people to continue to find ways to express their beliefs even under authoritarian government.

A friend here has been encouraging me to read Leon Feuchtwanger's Erfolg as an eerily prescient portrait of Munich on the eve of Hitler's rise. We'll see if I can stomach reading it this quarter.

I think I'm going to have to go in search of encouraging stories about resistance to oppression, or else join >8 LolaWalser: and creatively reinterpret the theme.

Bakhtin's writing on the carnavalesque feels like it might be worth revisiting. And the second part of Andrei Sinyavsky's Ivan the Fool has some encouraging things to say about the ability of people to continue to find ways to express their beliefs even under authoritarian government.

A friend here has been encouraging me to read Leon Feuchtwanger's Erfolg as an eerily prescient portrait of Munich on the eve of Hitler's rise. We'll see if I can stomach reading it this quarter.

35SassyLassy

>33 berthirsch: Thanks for the article. I particularly like the quote Literature is the enemy of any dictatorship

re: The Feast of the Goat... That was one of the novels that inspired the idea of dictatorships as a theme. An amazing work.

>34 spiphany: It's hard to discuss this topic without politics! Writings about resistance to oppression are both welcome and valid, as is Lola's interpretation.

re: The Feast of the Goat... That was one of the novels that inspired the idea of dictatorships as a theme. An amazing work.

>34 spiphany: It's hard to discuss this topic without politics! Writings about resistance to oppression are both welcome and valid, as is Lola's interpretation.

36spiphany

>35 SassyLassy: Well, it was more not wanting to derail this thread with a heated discussion about current events which some subset of the population clearly sees very differently than I do (probably not too many in a group called "reading globally," but all the same).

I do think there is value in reading stories of dictators and tyranny as a way of bearing witness, but there are few books I had been thinking of reading that are now probably going to have to wait.

I just noticed while looking back over the titles in this thread that nobody has brought up the topic of plays. This is interesting, because I feel like the theme of demagoguery on the one hand and oppression on the other (if not always dictatorships per se) is quite common in a literary form that is meant for performance and thus often has a political function.

I'm most familiar with German drama, and it's realy striking how many plays -- particularly from the second half of the twentieth century, for obvious reasons -- deal with this theme. The ones that spring to mind are Max Frisch, Andorra and Peter Weiss, The Investigation and Marat/Sade, but there are plenty of others.

And of course, the "monarch play" is a well-established genre in European theater, and some of these include stories about monarchs-as-dictators or resistance to tyranny, starting with Shakespeare (Julius Caesar and Schiller Wilhelm Tell).

I do think there is value in reading stories of dictators and tyranny as a way of bearing witness, but there are few books I had been thinking of reading that are now probably going to have to wait.

I just noticed while looking back over the titles in this thread that nobody has brought up the topic of plays. This is interesting, because I feel like the theme of demagoguery on the one hand and oppression on the other (if not always dictatorships per se) is quite common in a literary form that is meant for performance and thus often has a political function.

I'm most familiar with German drama, and it's realy striking how many plays -- particularly from the second half of the twentieth century, for obvious reasons -- deal with this theme. The ones that spring to mind are Max Frisch, Andorra and Peter Weiss, The Investigation and Marat/Sade, but there are plenty of others.

And of course, the "monarch play" is a well-established genre in European theater, and some of these include stories about monarchs-as-dictators or resistance to tyranny, starting with Shakespeare (Julius Caesar and Schiller Wilhelm Tell).

37BLBera

Also on Trujillo: Julia Alvarez's In the Time of the Butterflies. The Feast of the Goat is also great.

38chlorine

I've finished Piégés par Staline (Trapped by Stalin) by Nicolas Jallot.

As a book I did not find it great (there are lots of repetitions and sometimes it's a bit hard to see the author's point), but as a documentary I found it quite interesting.

Instead of focusing on the lives of the people who came back to USSR just after the war, he focuses on the reasons: why did Stalin offer an amnisity to the people who fled during the revolution? Why did the people want to go back? What was the role of the French state in this?

It's a quick read so I'd recommend it to anyone interested in this part of history, otherwise feel free to give it a pass.

For what it's worth a bit of personal history: my mother's father was born in Russia and fled during the civil war with his mother. When she was a student (this must have been circa 1966), my mother was offered to go on a trip to USSR. This trip was offered to children of Russien emigrants, to show them how great USSR was. Reading this book made me retroactively fear for my mother's safety. Arguably she went there long after the facts in this book, but I'm all the more glad they let her come back to France after reading this book. :)

As a book I did not find it great (there are lots of repetitions and sometimes it's a bit hard to see the author's point), but as a documentary I found it quite interesting.

Instead of focusing on the lives of the people who came back to USSR just after the war, he focuses on the reasons: why did Stalin offer an amnisity to the people who fled during the revolution? Why did the people want to go back? What was the role of the French state in this?

It's a quick read so I'd recommend it to anyone interested in this part of history, otherwise feel free to give it a pass.

For what it's worth a bit of personal history: my mother's father was born in Russia and fled during the civil war with his mother. When she was a student (this must have been circa 1966), my mother was offered to go on a trip to USSR. This trip was offered to children of Russien emigrants, to show them how great USSR was. Reading this book made me retroactively fear for my mother's safety. Arguably she went there long after the facts in this book, but I'm all the more glad they let her come back to France after reading this book. :)

39mabith

I've also temporarily put aside some of my planned books for this theme, but I should pick it back up. I'd been going to start one of Victor Klemperer's diaries, and Irmgard Keun's Child of All Nations. In the end I think that this kind of reading will help us be active in fighting against hateful rhetoric, but I definitely need a little time first.

40mabith

I think most of Ismail Kadare's books at least loosely fit this theme!

Twilight of the Eastern Gods by Ismail Kadare

I'm so glad I have a friend who is a diehard Kadare fan, because otherwise I might not have encountered him. I've only read three books by him, but I feel like he's one of those authors who excels at putting layers into his books. There is a straight story that's enjoyable on it's own and then there's the allegory, the historical undercurrents, the absurdist humor, etc...

This book is quite autobiographical covering his time in Moscow at the Gorky Institute, to the extent of using the real names of his fellow students (though presenting caricatures of them). Kadare is an Albanian and was in Moscow from 1958-1960, just before relations between Albania and the USSR cooled. He was also there when Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize and witnessed the media campaign against him and this is a major focus of the book.

There was a sort of lull in the book for me occupy about the second quarter of it, too much angsty romance that didn't feel genuine. Once I got to the halfway point I reengaged and enjoyed the rest of the book. The Siege is still my favorite that I've read by him.

Twilight of the Eastern Gods by Ismail Kadare

I'm so glad I have a friend who is a diehard Kadare fan, because otherwise I might not have encountered him. I've only read three books by him, but I feel like he's one of those authors who excels at putting layers into his books. There is a straight story that's enjoyable on it's own and then there's the allegory, the historical undercurrents, the absurdist humor, etc...

This book is quite autobiographical covering his time in Moscow at the Gorky Institute, to the extent of using the real names of his fellow students (though presenting caricatures of them). Kadare is an Albanian and was in Moscow from 1958-1960, just before relations between Albania and the USSR cooled. He was also there when Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize and witnessed the media campaign against him and this is a major focus of the book.

There was a sort of lull in the book for me occupy about the second quarter of it, too much angsty romance that didn't feel genuine. Once I got to the halfway point I reengaged and enjoyed the rest of the book. The Siege is still my favorite that I've read by him.

41BLBera

Human Acts tells the story of the 1980 massacre of protestors in the city of Gwangju, a city in southern South Korea. Told from various points of view of people who participated in or who were affected by the massacre and its aftermath, this is a heartbreaking story that is, as the translator Deborah Smith says, "a reminder of the human acts of which we are all capable."

Han Kang's poetic writing makes the scenes of brutality and torture all the more shocking. One protestor remembers what prompted his participation: "Those snapshot moments, when it seemed we'd all performed the miracle of stepping outside the shell of our own selves, one person's tender skin coming into grazed contact with another, felt as though they were rethreading the sinews of that world heart, patching up the fissures from which blood had flowed, making it beat again."

Each voice, from that of the middle school student and his mother, to the young women factory worker, to the writer trying to make sense of what happened, each adds to the story, revealing a crime that the world should recognize. An important, breathtaking novel.

We hear a lot about the repressive regime in North Korea, but it sounds like South Korea is also repressive. I had never heard about this incident but will look for more information after reading this wonderful novel.

Note: This is not for the faint of heart. It is a novel that will stay with me for a long time. Han Kang writes beautifully of horrific events - I think a lot of credit goes to the translator.

42SassyLassy

>41 BLBera: A novel I had not heard of, but by the sounds of it, definitely one I should track down. Thanks for the review. I keep meaning to read The Vegetarian but haven't seen that as yet in my travels.

43cindydavid4

Off topic - I am new to LT and just discovered this topic. Having themes like this is so up my alley; Im sorry I missed out on some of them but suspect I can go read the discussion. Eager to jump into this one

I didn't notice that this was mentioned, but a horrifying book to read is King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa .

For a fictional account of Pinochet's Chile, read The House of Spirits and Eva Luna, by Isabelle Allende.

I didn't notice that this was mentioned, but a horrifying book to read is King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa .

For a fictional account of Pinochet's Chile, read The House of Spirits and Eva Luna, by Isabelle Allende.

44spiphany

I just finished Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz, which turned out to be especially timely in some ways that I hadn't expected. The novel is a love story set in Nero's Rome; the slaughter of the Christians after the great fire has a central place in the story.

The book has a bit of an implicit Christian message, I guess, but Sienkiewicz doesn't really proselytize the reader -- what struck me (as someone who doesn't consider herself a believer) was that he makes the emergence of Christianity and the reasons why early Christians embraced the religion plausible in the historical context. Christianity seems to be an anecdote to the pleasure-seeking, egoism, and arbitrary cruelty of Nero and his court (and even of the Roman gods, who are viewed with some supersition, but largely as beings to be appeased, tricked, or bribed). I found the characters -- or rather, the love story -- not entirely convincing, but on a more philosophical level the novel mostly works. However, I have extremely mixed feelings about the end of the novel. The killing of the Christians in the amphitheater is described in nauseating detail, and while revulsion may have been the effect the author intended, the passivity of the Christians going to their martyrdom is particularly unnerving in this context. As is Vinicius's blind determination to save his Lygia from a terrible fate: while we are supposed to root for these two characters surviving and being reunited, their fellow Christians go unprotesting to their deaths by the hundred, and somehow everyone is resigned to this, even embraces it, because it will unite them with Christ.

While reading, I found myself reflecting on the difference between tyranny and fascism. Fascism may not be quite the right word here, but I'm thinking particularly of the heavily bureaucratized nature of the authoritarian governments in Europe in the twentieth century. The impenetrable, ideology-driven bureaucracy in which the atrocities are embedded is part of what gives Nazi Germany its horror. Nero seems fairly harmless by comparison, at least until his egomania gets out of control and he arranges for Rome to be set alight as inspiration for his tragic poetry.

Nero's government is an arbitrary one based on his moods and narcissism; although he does seem to have police forces to enforce his will, much of his power seems to come from the vast funds he uses to put on private and public displays, and from the other members of his court, who try to flatter and appease and influence him to their own ends. Nero -- whom the characters in the novel refer to, when he is not present, as "the copper-bearded one" -- feels very familiar, as does his use of public spectacles to whip up the emotions of the masses. The novel is a reminder that reality TV and viral social media may be relatively new, but the principle is not. Part of Nero's fascination seems to be precisely his arbitrariness, the danger he presents. One of the characters talks about gambling in this context -- yes, it would be safer not to bet, but that would take away the anticipation and the thrill of possibly winning.

The book has a bit of an implicit Christian message, I guess, but Sienkiewicz doesn't really proselytize the reader -- what struck me (as someone who doesn't consider herself a believer) was that he makes the emergence of Christianity and the reasons why early Christians embraced the religion plausible in the historical context. Christianity seems to be an anecdote to the pleasure-seeking, egoism, and arbitrary cruelty of Nero and his court (and even of the Roman gods, who are viewed with some supersition, but largely as beings to be appeased, tricked, or bribed). I found the characters -- or rather, the love story -- not entirely convincing, but on a more philosophical level the novel mostly works. However, I have extremely mixed feelings about the end of the novel. The killing of the Christians in the amphitheater is described in nauseating detail, and while revulsion may have been the effect the author intended, the passivity of the Christians going to their martyrdom is particularly unnerving in this context. As is Vinicius's blind determination to save his Lygia from a terrible fate: while we are supposed to root for these two characters surviving and being reunited, their fellow Christians go unprotesting to their deaths by the hundred, and somehow everyone is resigned to this, even embraces it, because it will unite them with Christ.

While reading, I found myself reflecting on the difference between tyranny and fascism. Fascism may not be quite the right word here, but I'm thinking particularly of the heavily bureaucratized nature of the authoritarian governments in Europe in the twentieth century. The impenetrable, ideology-driven bureaucracy in which the atrocities are embedded is part of what gives Nazi Germany its horror. Nero seems fairly harmless by comparison, at least until his egomania gets out of control and he arranges for Rome to be set alight as inspiration for his tragic poetry.

Nero's government is an arbitrary one based on his moods and narcissism; although he does seem to have police forces to enforce his will, much of his power seems to come from the vast funds he uses to put on private and public displays, and from the other members of his court, who try to flatter and appease and influence him to their own ends. Nero -- whom the characters in the novel refer to, when he is not present, as "the copper-bearded one" -- feels very familiar, as does his use of public spectacles to whip up the emotions of the masses. The novel is a reminder that reality TV and viral social media may be relatively new, but the principle is not. Part of Nero's fascination seems to be precisely his arbitrariness, the danger he presents. One of the characters talks about gambling in this context -- yes, it would be safer not to bet, but that would take away the anticipation and the thrill of possibly winning.

45mabith

The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule by Igort

This non-fiction comic is the result of years of travel and interviews with people in Russia and Ukraine. Igort is the pen name of Igor Tuveri, an Italian artist. The book is sometimes more illustrated text than comic and it all flows around.