StevenTX's 2014 Reading Log - Vol. II

Esto es una continuación del tema StevenTX's 2014 Reading Log - Vol. I.

Este tema fue continuado por StevenTX's 2014 Reading Log - Vol. III.

CharlasClub Read 2014

Únete a LibraryThing para publicar.

Este tema está marcado actualmente como "inactivo"—el último mensaje es de hace más de 90 días. Puedes reactivarlo escribiendo una respuesta.

1StevenTX

On the Reading Shelf

These are the books I'm planning to read over the next few months. My goal is to read an average of at least one book from each category per month. The cover you see here is not necessarily the edition I'm reading.

Classics of Western Literature

Reading chronologically, re-reading works I read more than 20 years ago. In some cases I will be reading only selections from the "Complete Works" shown below.

Science Fiction

Reading chronologically, taking most ideas from Anatomy of Wonder.

Fantasy, Horror, Decadent, Surrealist and Gothic Fiction

Reading chronologically, taking ideas from a variety of sources.

1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die

Reading chronologically from the list.

LT Group Themes

Themed selections for groups such as Literary Centennials and Reading Globally. Selections are taken from the "1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die" list whenever possible. This category is highly subject to change.

Books in Progress and Books in Series

Finishing books and series that I've already started but don't necessarily fit any of the categories above.

These are the books I'm planning to read over the next few months. My goal is to read an average of at least one book from each category per month. The cover you see here is not necessarily the edition I'm reading.

Classics of Western Literature

Reading chronologically, re-reading works I read more than 20 years ago. In some cases I will be reading only selections from the "Complete Works" shown below.

Science Fiction

Reading chronologically, taking most ideas from Anatomy of Wonder.

Fantasy, Horror, Decadent, Surrealist and Gothic Fiction

Reading chronologically, taking ideas from a variety of sources.

1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die

Reading chronologically from the list.

LT Group Themes

Themed selections for groups such as Literary Centennials and Reading Globally. Selections are taken from the "1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die" list whenever possible. This category is highly subject to change.

Books in Progress and Books in Series

Finishing books and series that I've already started but don't necessarily fit any of the categories above.

2StevenTX

Index to My 2014 Reading

The book titles link to the work page; the date read links to my Club Read post and discussion.

Anthony, Piers - Eroma - August 9

Aristophanes - The Acharnians - January 18

- The Knights - February 3

- The Wasps - August 31

- Peace - September 7

- Thesmophoriazusae - September 8

Azuela, Mariano - The Underdogs - August 2

Banville, John - Kepler - August 25

- The Newton Letter - September 6

Barbusse, Henri - Under Fire - March 18

Beckett, Samuel - How It Is - August 17

Blatnik, Andrej - Skinswaps - April 29

- Law of Desire: Stories - May 1

Brown, Charles Brockden - Wieland - September 3

Cervantes, Miguel de - The Trials of Persiles and Sigismunda - May 29

Chevallier, Gabriel - Fear: A Novel of World War I - April 10

Coover, Robert - The Origin of the Brunists - April 18

- The Brunist Day of Wrath - June 10

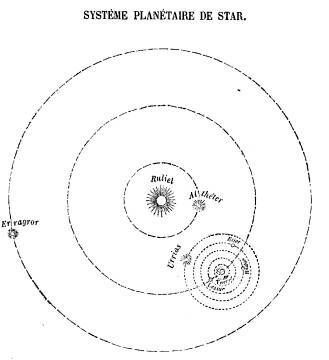

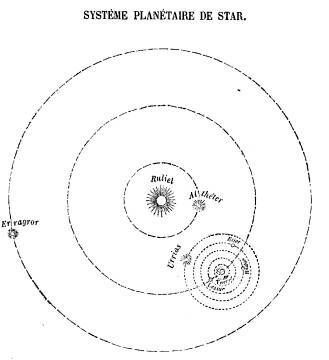

Defontenay, C. I. - Star (Psi Cassiopeia) - June 29

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal - The Conquest of New Spain - July 16

Euripides - The Suppliant Women - January 22

- The Phoenician Women - September 14

- Rhesus - September 16

- Orestes - September 17

Fielding, Henry - Shamela - August 8

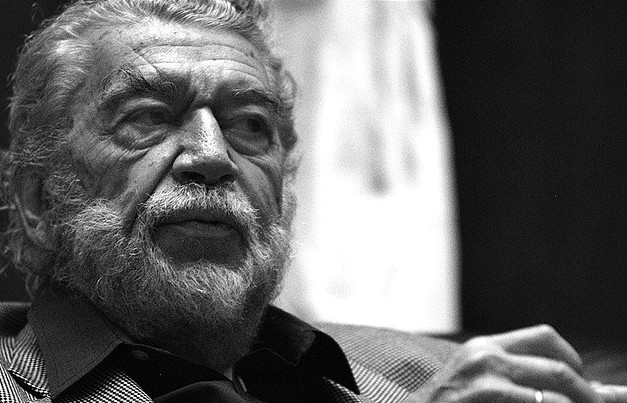

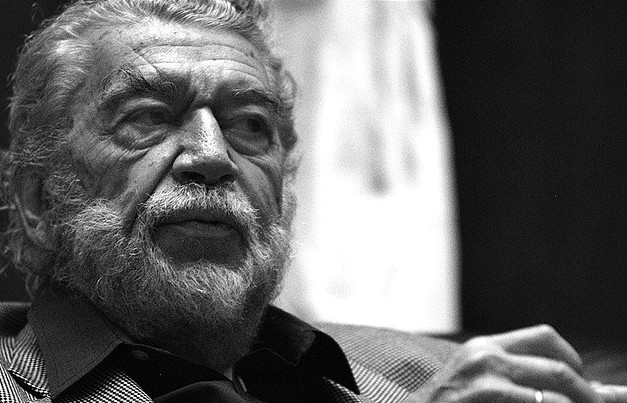

Fuentes, Carlos - The Death of Artemio Cruz - September 1

Godwin, William - Things As They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams - January 23

Grimmelshausen, Hans Jacob Christoffel von - The Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus - September 13

Hale, Edward Everett - The Brick Moon - August 16

Herodotus - The Histories - January 12

Jancar, Drago - The Tree with No Name - May 26

Jiménez, Juan Ramón - Platero and I - January 29

Levé, Edouard - Works -

Mofolo, Thomas - Chaka the Zulu - February 21

Montalvo, Garci Rodríguez de - Amadis of Gaul: Books I and II and Amadis of Gaul: Books III and IV - April 27

Paskov, Victor - A Ballad for Georg Henig - August 7

Paz, Octavio - The Labyrinth of Solitude and Other Writings - June 2

Perce, Elbert - Gulliver Joi - May 27

Radcliffe, Ann - The Italian - May 13

Rhodes, Richard - The Making of the Atomic Bomb - March 7

Robbe-Grillet, Alain - A Sentimental Novel - May 14

Rojas, Fernando de - La Celestina - January 2

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - Julie; or, The New Heloise - July 19

Roussel, Raymond - Locus Solus - January 11

Rushdie, Salman - Grimus - February 28

Sand, George - Laura: A Journey into the Crystal - August 10

Sarmiento, Domingo F. - Facundo: or, Civilization and Barbarism - January 4

Seaborn, Adam - Symzonia: A Voyage of Discovery - January 23

Shahnour, Shahan - Retreat without Song - September 4

Shelley, Mary - Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus - March 1

Thucydides - The History of the Peloponnesian War - August 19

Torva, Lucretia - Sex!: The Punctuation Mark of Life - April 28

Trueman, Chrysostom - The History of a Voyage to the Moon - July 13

Tucker, George - A Voyage to the Moon - March 19

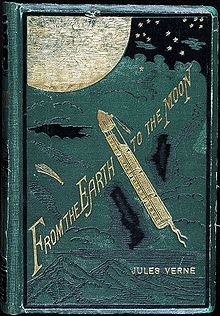

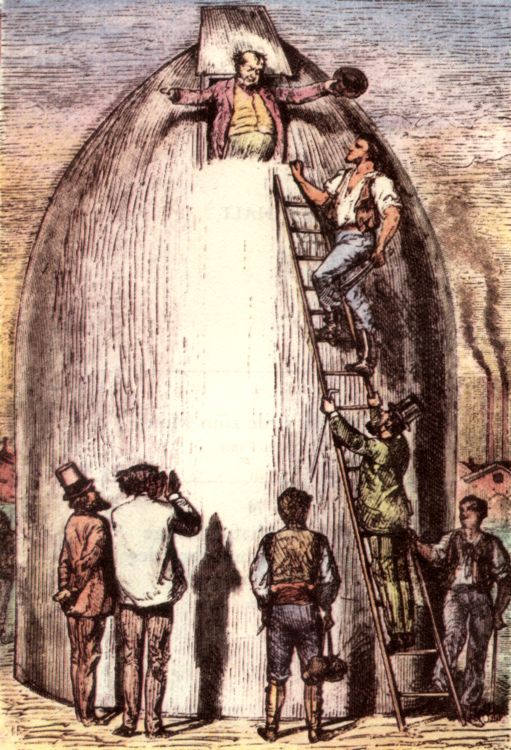

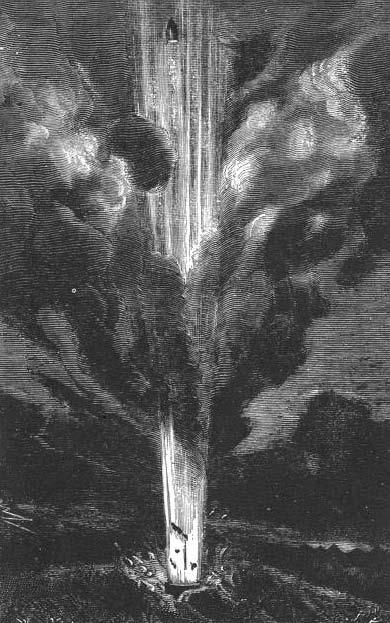

Verne, Jules - From the Earth to the Moon - July 22

- Around the Moon - July 25

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea - September 19

Wells, H. G. - The World Set Free - March 20

Witkiewicz, Stanislaw - Insatiability - August 5

Woolf, Virginia - Night and Day - January 7

Zola, Émile - The Belly of Paris - February 20

2013 Index

The book titles link to the work page; the date read links to my Club Read post and discussion.

Anthony, Piers - Eroma - August 9

Aristophanes - The Acharnians - January 18

- The Knights - February 3

- The Wasps - August 31

- Peace - September 7

- Thesmophoriazusae - September 8

Azuela, Mariano - The Underdogs - August 2

Banville, John - Kepler - August 25

- The Newton Letter - September 6

Barbusse, Henri - Under Fire - March 18

Beckett, Samuel - How It Is - August 17

Blatnik, Andrej - Skinswaps - April 29

- Law of Desire: Stories - May 1

Brown, Charles Brockden - Wieland - September 3

Cervantes, Miguel de - The Trials of Persiles and Sigismunda - May 29

Chevallier, Gabriel - Fear: A Novel of World War I - April 10

Coover, Robert - The Origin of the Brunists - April 18

- The Brunist Day of Wrath - June 10

Defontenay, C. I. - Star (Psi Cassiopeia) - June 29

Díaz del Castillo, Bernal - The Conquest of New Spain - July 16

Euripides - The Suppliant Women - January 22

- The Phoenician Women - September 14

- Rhesus - September 16

- Orestes - September 17

Fielding, Henry - Shamela - August 8

Fuentes, Carlos - The Death of Artemio Cruz - September 1

Godwin, William - Things As They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams - January 23

Grimmelshausen, Hans Jacob Christoffel von - The Adventures of Simplicius Simplicissimus - September 13

Hale, Edward Everett - The Brick Moon - August 16

Herodotus - The Histories - January 12

Jancar, Drago - The Tree with No Name - May 26

Jiménez, Juan Ramón - Platero and I - January 29

Levé, Edouard - Works -

Mofolo, Thomas - Chaka the Zulu - February 21

Montalvo, Garci Rodríguez de - Amadis of Gaul: Books I and II and Amadis of Gaul: Books III and IV - April 27

Paskov, Victor - A Ballad for Georg Henig - August 7

Paz, Octavio - The Labyrinth of Solitude and Other Writings - June 2

Perce, Elbert - Gulliver Joi - May 27

Radcliffe, Ann - The Italian - May 13

Rhodes, Richard - The Making of the Atomic Bomb - March 7

Robbe-Grillet, Alain - A Sentimental Novel - May 14

Rojas, Fernando de - La Celestina - January 2

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques - Julie; or, The New Heloise - July 19

Roussel, Raymond - Locus Solus - January 11

Rushdie, Salman - Grimus - February 28

Sand, George - Laura: A Journey into the Crystal - August 10

Sarmiento, Domingo F. - Facundo: or, Civilization and Barbarism - January 4

Seaborn, Adam - Symzonia: A Voyage of Discovery - January 23

Shahnour, Shahan - Retreat without Song - September 4

Shelley, Mary - Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus - March 1

Thucydides - The History of the Peloponnesian War - August 19

Torva, Lucretia - Sex!: The Punctuation Mark of Life - April 28

Trueman, Chrysostom - The History of a Voyage to the Moon - July 13

Tucker, George - A Voyage to the Moon - March 19

Verne, Jules - From the Earth to the Moon - July 22

- Around the Moon - July 25

- 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea - September 19

Wells, H. G. - The World Set Free - March 20

Witkiewicz, Stanislaw - Insatiability - August 5

Woolf, Virginia - Night and Day - January 7

Zola, Émile - The Belly of Paris - February 20

2013 Index

3StevenTX

2014 Statistics

Summary of Books Read

66 - books read

49 - novels

9 - plays

5 - history

1 - memoir

2 - short story collections

1 - essay collections

Authors

54 - different authors

31 - authors new to me

56 - books by male authors

7 - books by female authors

4 - books by anonymous or unknown authors

Books Read by Author's Nationality

13 - French

12 - English

11 - Ancient Greek

10 - American

5 - Spanish

3 - Slovene

3 - Mexican

3 - Irish

1 - Argentine

1 - Lesothan

1 - Indian

1 - Polish

1 - Bulgarian

1 - Armenian

1 - German

Books Read by Original Language

25 - English

14 - French

11 - Greek

9 - Spanish

3 - Slovene

1 - Sesotho

1 - Polish

1 - Bulgarian

1 - Armenian

1 - German

Books Read by Decade of First Publication

11 - Classical era

1 - 15th century

1 - 16th century

3 - 17th century

1 - 1740s

1 - 1760s

4 - 1790s

2 - 1810s

2 - 1820s

1 - 1840s

2 - 1850s

3 - 1860s

4 - 1870s

1 - 1880s

1 - 1900s

5 - 1910s

2 - 1920s

2 - 1930s

1 - 1950s

3 - 1960s

1 - 1970s

4 - 1980s

2 - 1990s

4 - 2000s

5 - 2010s

2013 Statistics

2012 statistics

Summary of Books Read

66 - books read

49 - novels

9 - plays

5 - history

1 - memoir

2 - short story collections

1 - essay collections

Authors

54 - different authors

31 - authors new to me

56 - books by male authors

7 - books by female authors

4 - books by anonymous or unknown authors

Books Read by Author's Nationality

13 - French

12 - English

11 - Ancient Greek

10 - American

5 - Spanish

3 - Slovene

3 - Mexican

3 - Irish

1 - Argentine

1 - Lesothan

1 - Indian

1 - Polish

1 - Bulgarian

1 - Armenian

1 - German

Books Read by Original Language

25 - English

14 - French

11 - Greek

9 - Spanish

3 - Slovene

1 - Sesotho

1 - Polish

1 - Bulgarian

1 - Armenian

1 - German

Books Read by Decade of First Publication

11 - Classical era

1 - 15th century

1 - 16th century

3 - 17th century

1 - 1740s

1 - 1760s

4 - 1790s

2 - 1810s

2 - 1820s

1 - 1840s

2 - 1850s

3 - 1860s

4 - 1870s

1 - 1880s

1 - 1900s

5 - 1910s

2 - 1920s

2 - 1930s

1 - 1950s

3 - 1960s

1 - 1970s

4 - 1980s

2 - 1990s

4 - 2000s

5 - 2010s

2013 Statistics

2012 statistics

4StevenTX

I'm belatedly beginning a new thread for the new quarter and hoping to get back into the reading groove now that our house redecorating project is winding down.

6StevenTX

Fear: A Novel of World War I by Gabriel Chevallier

First published 1930 as La Peur

English translation 2011 by Malcolm Imrie

Review of an ARC provided via NetGalley

"Would you like to know the chief occupation in war, the only one that matters: I was afraid."

What sets Fear apart from most other autobiographical war novels is the author's stark and unapologetic admission that he was afraid, not just at the most intense moments of combat, but all the time. Nor was he in any way different from his fellow infantrymen. "We were cowards and we knew it and we could be nothing else. The body was in charge and fear gave the orders."

The narrator of the novel, Jean Dartemont, is a 19-year-old student when he is called up for military service late in 1914. His initial feelings of mixed apprehension and curiosity soon turn to disgust for the mechanical and irrational aspects of military life. Nine months later, its training complete, Dartemont's unit is marched down endless dusty roads into the combat zone. "We had just marched over the crest of a hill, and suddenly there before us lay the front line, roaring with all its mouths of fire, blazing like some infernal factory where monstrous crucibles melted human flesh into a bloody lava."

Dartemont serves the entire rest of the war as a private in the French infantry. His experiences run the gamut from front line combat, to boring rear area duty, to special assignments. At one point he is wounded, recuperates, spends a few days leave at home, and is then sent back to the front. The author's description of trench warfare is as intense, harrowing, and grisly as any you will find. Throughout it all there is fear, but most especially during intense artillery bombardments. "Every explosion of the bombardment hits me in the chest. I am ashamed of the sick animal wallowing in filth that I have become, but all my strings have snapped. My fear is abject. It makes me want to spit on myself."

The narrator's attitude toward war and those who make it is equally frank. Speaking of the beginning of the war, he says "In a few short days, civilisation was wiped out. In a few short days, all our leaders became abject failures. For their role, their only role that mattered, was precisely to prevent all this." Dartemont also blames the Church for "ordering me to kill my brothers," he blames women who insist that their sons and lovers come back as heroes, he blames flag-waving patriots who shame others into dying for empty causes like "national honour," and he blames the industrialists who make war for profit. But ultimately the fault is with mankind itself. "Men are sheep. This fact makes armies and wars possible."

Gabriel Chevallier did not publish his fictionalized war memoir until 1930, by which time memories of the horrors of war were fading into nostalgia and Europe was rearming for another war. His strident anti-war novel met with a cool reception, and was eventually removed from publication lest it impair French morale. Its subsequent obscurity is unfortunate, for Fear is one of the most powerful, vivid, and convincing war novels I have ever read.

First published 1930 as La Peur

English translation 2011 by Malcolm Imrie

Review of an ARC provided via NetGalley

"Would you like to know the chief occupation in war, the only one that matters: I was afraid."

What sets Fear apart from most other autobiographical war novels is the author's stark and unapologetic admission that he was afraid, not just at the most intense moments of combat, but all the time. Nor was he in any way different from his fellow infantrymen. "We were cowards and we knew it and we could be nothing else. The body was in charge and fear gave the orders."

The narrator of the novel, Jean Dartemont, is a 19-year-old student when he is called up for military service late in 1914. His initial feelings of mixed apprehension and curiosity soon turn to disgust for the mechanical and irrational aspects of military life. Nine months later, its training complete, Dartemont's unit is marched down endless dusty roads into the combat zone. "We had just marched over the crest of a hill, and suddenly there before us lay the front line, roaring with all its mouths of fire, blazing like some infernal factory where monstrous crucibles melted human flesh into a bloody lava."

Dartemont serves the entire rest of the war as a private in the French infantry. His experiences run the gamut from front line combat, to boring rear area duty, to special assignments. At one point he is wounded, recuperates, spends a few days leave at home, and is then sent back to the front. The author's description of trench warfare is as intense, harrowing, and grisly as any you will find. Throughout it all there is fear, but most especially during intense artillery bombardments. "Every explosion of the bombardment hits me in the chest. I am ashamed of the sick animal wallowing in filth that I have become, but all my strings have snapped. My fear is abject. It makes me want to spit on myself."

The narrator's attitude toward war and those who make it is equally frank. Speaking of the beginning of the war, he says "In a few short days, civilisation was wiped out. In a few short days, all our leaders became abject failures. For their role, their only role that mattered, was precisely to prevent all this." Dartemont also blames the Church for "ordering me to kill my brothers," he blames women who insist that their sons and lovers come back as heroes, he blames flag-waving patriots who shame others into dying for empty causes like "national honour," and he blames the industrialists who make war for profit. But ultimately the fault is with mankind itself. "Men are sheep. This fact makes armies and wars possible."

Gabriel Chevallier did not publish his fictionalized war memoir until 1930, by which time memories of the horrors of war were fading into nostalgia and Europe was rearming for another war. His strident anti-war novel met with a cool reception, and was eventually removed from publication lest it impair French morale. Its subsequent obscurity is unfortunate, for Fear is one of the most powerful, vivid, and convincing war novels I have ever read.

7rebeccanyc

Fascinating!

9Linda92007

Fabulous review of Fear: A Novel of World War I, Steven. Sounds like one to add to the list.

10baswood

Wow, I had never heard of Fear: A novel of World war I. Great review Steven. Interesting to learn that it has been left to slide into obscurity.

11avidmom

>1 StevenTX: Interesting collection of books! Looking forward to your thoughts on the Paz book.

>6 StevenTX: Sounds like a great book. (The "grisly" might be too much for me though.) Interesting that they stopped publication unless it "impair French morale." Powerful stuff. Who can argue with his list of people, et. al. for war?

>6 StevenTX: Sounds like a great book. (The "grisly" might be too much for me though.) Interesting that they stopped publication unless it "impair French morale." Powerful stuff. Who can argue with his list of people, et. al. for war?

12NanaCC

>6 StevenTX: Terrific review of Fear: A Novel of World War I. I might have to add it to my ever growing wish list of books related to the Great War.

13SassyLassy

Excellent review. The idea that the author actually addresses why the men who make up the armies continue to be complicit in battle is reason alone to read this book: Men are sheep. This fact makes armies and wars possible, but that he also addressed the sheer terror as well, makes him someone to not just read, but to also absorb.

14fannyprice

Great review of Fear. I'll definitely be reading this one at some point.

15StevenTX

>11 avidmom: Actually I probably understated the violence and gore. "Horrific" might be a better term than "grisly." There are scenes and smells of blood, viscera and excrement throughout, as well as gut-wrenching depictions of suffering on the battlefield and in the hospital. And even this is a feeble understatement.

>13 SassyLassy: The author put most of his anti-war diatribe in the first chapter, which probably wasn't the best approach. It's an unproven thesis until you've read his experiences of three years of war. I couldn't help but compare this book with the other famous French war memoir, Under Fire, which I had recently read. Henri Barbusse, writing at mid-war, was at least optimistic that the horrors of WWI would convince humanity never to do it again. He put the blame on the structure of human society, something that could be corrected. Chevallier, more pessimistic, blames human nature itself. He sees that there will be no end to war and inhumanity.

>13 SassyLassy: The author put most of his anti-war diatribe in the first chapter, which probably wasn't the best approach. It's an unproven thesis until you've read his experiences of three years of war. I couldn't help but compare this book with the other famous French war memoir, Under Fire, which I had recently read. Henri Barbusse, writing at mid-war, was at least optimistic that the horrors of WWI would convince humanity never to do it again. He put the blame on the structure of human society, something that could be corrected. Chevallier, more pessimistic, blames human nature itself. He sees that there will be no end to war and inhumanity.

17cabegley

Just adding to the acclaim. That was a great review of Fear, and certainly makes me interested in reading it.

18StevenTX

The Origin of the Brunists by Robert Coover

First published 1966

The Origin of the Brunists is a novel which uses bizarre events to illuminate the lives and ideals of commonplace people. It is set in the 1960s in the town of West Condon, somewhere in the American Midwest. West Condon is a blue collar town with a high proportion of Italian immigrants. Its chief source of livelihood is a single coal mine, Deepwater Number 9, but the coal industry is in decline, and so is the town. A few days after New Years, tragedy strikes: There is an explosion in the mine. Hundreds of panicked workers rush for the exits. Most make it out alive, but 98 are trapped. Days later, rescuers reach the trapped miners. All are dead from burns or asphyxiation but one, Giovanni Bruno, and he is comatose.

When Bruno regains consciousness, his first words are of having been saved by an apparition in the form of a white bird. His vision seems to coincide with that of another miner, a Nazarene minister, who left a cryptic dying message for his wife. A local mystic sees these visions as confirmation of spiritual messages she has received prophesying the end of the world. Before long, a cult is born which calls itself the Brunists. Within weeks the cult's existence becomes an issue which tears at the social fabric of West Condon.

Robert Coover tells this story through the eyes of a number of West Condon residents, but principally two: the skirt-chasing former athlete who now edits the town newspaper, and an aging mine foreman who fears he will never find work again if the mine doesn't reopen. The stress of the mine disaster and the cult seem to bring ordinary events into sharper focus: children rebel against their parents, teenagers clumsily explore sex, politicians and businessmen maneuver for power, ministers strive to control wavering congregations, husbands and wives have extramarital affairs, and gossip continuously feeds the fears, attitudes and prejudices of the community.

The Origin of the Brunists is an outstanding novel which illuminates the individual lives of its characters to produce an excellent composite portrait of an American small town. Yet at the same time it also examines the psychology of religious cults and movements and shows us America's media culture in its formative stages.

Robert Coover has just published a sequel to The Origin of the Brunists (48 years after the original!) titled The Brunist Day of Wrath.

Other books I have read by Robert Coover:

Pricksongs & Descants

Spanking the Maid

First published 1966

The Origin of the Brunists is a novel which uses bizarre events to illuminate the lives and ideals of commonplace people. It is set in the 1960s in the town of West Condon, somewhere in the American Midwest. West Condon is a blue collar town with a high proportion of Italian immigrants. Its chief source of livelihood is a single coal mine, Deepwater Number 9, but the coal industry is in decline, and so is the town. A few days after New Years, tragedy strikes: There is an explosion in the mine. Hundreds of panicked workers rush for the exits. Most make it out alive, but 98 are trapped. Days later, rescuers reach the trapped miners. All are dead from burns or asphyxiation but one, Giovanni Bruno, and he is comatose.

When Bruno regains consciousness, his first words are of having been saved by an apparition in the form of a white bird. His vision seems to coincide with that of another miner, a Nazarene minister, who left a cryptic dying message for his wife. A local mystic sees these visions as confirmation of spiritual messages she has received prophesying the end of the world. Before long, a cult is born which calls itself the Brunists. Within weeks the cult's existence becomes an issue which tears at the social fabric of West Condon.

Robert Coover tells this story through the eyes of a number of West Condon residents, but principally two: the skirt-chasing former athlete who now edits the town newspaper, and an aging mine foreman who fears he will never find work again if the mine doesn't reopen. The stress of the mine disaster and the cult seem to bring ordinary events into sharper focus: children rebel against their parents, teenagers clumsily explore sex, politicians and businessmen maneuver for power, ministers strive to control wavering congregations, husbands and wives have extramarital affairs, and gossip continuously feeds the fears, attitudes and prejudices of the community.

The Origin of the Brunists is an outstanding novel which illuminates the individual lives of its characters to produce an excellent composite portrait of an American small town. Yet at the same time it also examines the psychology of religious cults and movements and shows us America's media culture in its formative stages.

Robert Coover has just published a sequel to The Origin of the Brunists (48 years after the original!) titled The Brunist Day of Wrath.

Other books I have read by Robert Coover:

Pricksongs & Descants

Spanking the Maid

19SassyLassy

Enjoyed your review of The Origin of the Brunists. I read this after reading Coover's The Public Burning and was struck in both instances by his style. The follow up, after 48 years as you say, should be interesting. Thanks for adding that bit, I didn't know of it.

20rebeccanyc

I've never read any Robert Coover, but The Origin of the Brunists sounds interesting.

21kidzdoc

Great review of The Origin of the Brunists, Steven.

22labfs39

The Origin of the Brunists sounds like it does well what The Age of Miracles did very poorly: uses bizarre events to illuminate the lives and ideals of commonplace people.

23baswood

Excellent review of The Origin of the Brunists. I won't be tempted by this as it's not on any of my lists. A bit of a change of style for you or did you not realise that the book was written in the mid 20th century.

Are you still reading Amadis of Gaul

Are you still reading Amadis of Gaul

24StevenTX

>23 baswood: - Yes, I slipped up and actually read something written during my own lifetime, didn't I? It wasn't in my reading plans, but I got curious when I saw that fannyprice was getting a lot of interesting books as free advance reading copies from something called NetGalley. I looked into it and, even though I wasn't sure I'd meet their criteria as a "blogger," I decided to give it a try. I put in for four books, thinking I'd be lucky to get one of them. They sent me all four. Fear: A Novel of World War I was the first one, and a perfect fit for this year's WWI theme in Club Read. The second was The Brunist Day of Wrath, the sequel to The Origin of the Brunists which I owned but hadn't read. So that's why I read it just now. Only yesterday did I realize that the sequel I must now read is 1100 pages long. But it will be fun.

Yes, I'm still reading a couple of chapters a day from Amadis of Gaul. It's a much more sophisticated narrative and more interesting story than I expected. I can see why Don Quixote was such a big fan. It must be its length (1400 pages) that has kept it from being as popular as the Arthurian romances. I'm almost 2/3 through. Amadis has just killed the fire-breathing monster Endriago and reclaimed the Island of the Devil for the Emperor of Constantinople, winning lavish praise from the Emperor and his daughter Leonorina (a very beguiling 8-year-old). But Amadis is still pining for his secret love, Oriana daughter of King Lisuarte of Great Britain and the most beautiful woman in the world. He would be even more distraught if he knew that at this very moment Patin, the Emperor of Rome, is approaching British shores intent on claiming Princess Oriana as his bride.

Yes, I'm still reading a couple of chapters a day from Amadis of Gaul. It's a much more sophisticated narrative and more interesting story than I expected. I can see why Don Quixote was such a big fan. It must be its length (1400 pages) that has kept it from being as popular as the Arthurian romances. I'm almost 2/3 through. Amadis has just killed the fire-breathing monster Endriago and reclaimed the Island of the Devil for the Emperor of Constantinople, winning lavish praise from the Emperor and his daughter Leonorina (a very beguiling 8-year-old). But Amadis is still pining for his secret love, Oriana daughter of King Lisuarte of Great Britain and the most beautiful woman in the world. He would be even more distraught if he knew that at this very moment Patin, the Emperor of Rome, is approaching British shores intent on claiming Princess Oriana as his bride.

25OscarWilde87

Every time I read about Amadis of Gaul in your thread I get closer to actually reading it. I've already looked where I could get a copy. What you write about it definitely sounds intriguing!

26fannyprice

>24 StevenTX:, Steven, I had exactly the same experience with NetGalley. I thought, "there's no way I'll get any of these books!" so I requested like 35 books. I got most of them. Ooops.

27StevenTX

Amadis of Gaul by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo

First published 1508 in Castillian

English translation by Edwin Place and Herbert Behm 1974

Published as Amadis of Gaul: Books I and II

and Amadis of Gaul: Books III and IV

Anyone who has read Don Quixote should recognize the name Amadis of Gaul. He was Quixote's role model as the perfect example of a chivalrous knight-errant. By the time Cervantes wrote his novel, the story of Amadis had been in print in Spanish for over a century, and parts of it in a more primitive form had existed in Spanish and other languages since the 14th century. Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo collected and translated the early Amadis texts--which consisted at the time of three books--modified them and added a fourth book entirely of his own invention. He died in 1504, leaving his Amadis to be published posthumously in 1508.

The story of Amadis takes place at a time several generations before that of King Arthur. There is still a Roman Empire, as well as a Byzantine Empire, but Great Britain, Gaul and Spain are independent kingdoms. The tale begins with the meeting of Amadis's parents, King Perion of Gaul and Princess Elisena of Brittany. They have a secret moonlight tryst, then separate. Elisena becomes pregnant as a result, but manages to hide her condition from her parents. When she gives birth to Amadis, her maid takes the baby, puts him in a boat along with a note, a ring and a sword, and shoves him out to sea. He is found (of course), and reared by foster parents in Scotland who call him just "Child of the Sea." Years later Amadis's parents actually get married, but Elisena doesn't tell her husband about the child she bore and abandoned.

The Child of the Sea, having remarkable good looks, physical prowess and moral rectitude, desires nothing more than to become a knight. He finds a patron in King Lisuarte of Great Britain, and falls madly and permanently in love with the king's daughter Oriana. Just as Amadis is the most perfect knight in the world, Oriana is the most beautiful woman in the world. Amadis goes on one adventure after another, fighting other knights, rescuing captives, slaying giants, and doing battle with a fire-breathing monster. Along the way his parentage is disclosed, he learns his real name, and he finds that he has two brothers--both of them exemplary knights. His travels take him to the shores of Bohemia and the isles of Romania (obviously Montalvo's geography was a little fuzzy) and as far as Constantinople. He is aided from time to time by the mysterious sorceress Urganda the Unknown, and tangles more than once with her arch-enemy Arcalus the Enchanter.

Amadis pines constantly for his lady love, Oriana, who loves him just as much in return. They keep their affections secret from all but their closest friends, but when Fortune gives them a night together they make the most of it. Oriana gets pregnant, secretly bears a son named Esplandian, and in trying to hide him accidentally loses him in the woods where he is nursed by a lioness, then reared by a hermit. He is destined, as we are told many times, to become an even greater knight than Amadis and eventually Emperor of Constantinople.

The overriding theme of Amadis of Gaul is the institution of knight-errantry. A knight is expected to go in search of adventures which will add to his glory and honor. His first duty is to help maidens and matrons in need, but he is also to aid and defend the poor and downtrodden of either gender. He is devoutly religious and displays proper Christian virtues, but he fights for personal glory, not the glory of the Church. He also seeks to be worthy of his lady love, if he should have one. Those knights who do not have a lady are free to enjoy the bed of any willing maiden, but once a knight-errant has fallen in love--even if it is his own secret--he must be true to his lady, no matter how many years it will take him to win her. A knight's martial prowess reflects his moral worth, for God would not have made him strong unless he were good. This leads to a system of justice based on trial by combat. Even a beauty contest is decided by a joust, with the damsel whose champion emerges victorious being crowned most beautiful.

Knights-errant usually go about in full armor with their helmets secured, thus keeping their identity hidden. Inevitably this leads to several accidental battles between brothers, friends, father and son, etc. Amadis especially seems to make a fetish of secrecy, using assumed names on most of his adventures. (One wonders how he expects to earn glory if no one knows who he is.) In this and other respects, knights-errant are the precursors of our modern-day fictional costumed superheroes. In their less noble aspects they resemble Wild West gunfighters.

The first book of Amadis of Gaul consists of a series of loosely connected short adventures, some of which readers of Arthurian legends will easily recognize as having been borrowed from the exploits of Lancelot, Parzival, Tristan and Gawain. The second and third books, however, appear to have been heavily re-written by Montalvo to weave Amadis's adventures and those of his friends and brothers into a larger, more coherent story. The author keeps several quests going at once, shifting scenes to maintain the suspense. In the fourth book, which is Montalvo's own, action is on a much grander scale, as Amadis and Oriana are the focus of a clash of empires.

The novel regularly addresses several moral and emotional dilemmas. Are we obliged to sacrifice our personal honor for the general good or the welfare of our friends? (Amadis refuses to.) What do we do when our personal honor and our duty to our sovereign are at odds? (Amadis puts his pride before his king, and is praised for doing so.) And how do we handle that moment when we realize that we are past our prime and it is time to let the next generation take the spotlight?

The writing in Amadis of Gaul is the least stylized and formulaic of any of the romances of chivalry I have read. This is not to say that it is the best, or that the language is modern, but that the dialog and feelings of the characters are the most natural, and the actions are the most believable. This is especially true of the many combat scenes. Montalvo writes like a man who has been there. Every joust and every battle is distinctly different and filled with believable and vivid detail.

Montalvo followed up his Amadis with a volume called The Exploits of Esplandian (which he shamelessly plugs throughout Book IV). Other writers of various nationalities followed it up with their own sequels until, by Don Quixote's time, the Amadis franchise consisted of at least 24 volumes. The sequels, however, are markedly inferior to the original four books of Montalvo's as Cervantes himself tells us in Don Quixote. The only complete modern English translation is the edition in two volumes by Edwin Place and Herbert Behm, which is the one I am reviewing. It appears to be a very literal translation, preserving the occasional long and ornate phase at the expense of readability. For a work of such size and antiquity, there are surprisingly few explanatory notes or other aids. Robert Southey's 1803 translation is also widely available, but the prudish poet removed the few references to sexual activity and the female body, as well as some moral asides by Montalvo that he thought were boring. Southey's translation was published in three volumes, but it does contain all four original books. Sue Burke is publishing a translation of Amadis of Gaul on her blog in biweekly installments, but is only about half finished. If you want to sample the story, you can do so at http://amadisofgaul.blogspot.com/.

I found Amadis of Gaul to be often entertaining and occasionally moving or suspenseful even though the leading characters, as is typical of medieval romances, are unbelievably perfect. It would certainly be more widely read if it were shorter, but its length of 1400+ pages no doubt has intimidated translators, publishers and readers alike.

"The Knight-errant" by John Everett Millais shows what could be a typical scene from Amadis of Gaul, the rescuing of a damsel in distress. Amadis finds at least one damsel tied to a tree by a would-be rapist, but her state of dress isn't specified. Note that Millais's knight is wearing armor from a period later than Montalvo's. His moon is also impossible--for the crescent to be perpendicular to the horizon the sun would also have to be in the sky.

This painting, "I Am Sir Launcelot du Lake" by N. C. Wyeth, is probably a more accurate depiction of the armor worn by Amadis than the Millais painting. The helmet did not have a hinged visor, so it had to be unlaced and removed to reveal the knight's face. The body was covered mostly by chain mail, with armor plate in the more exposed areas, but this appears to have varied according to the wearer's wealth and taste. The fallen horse in the background is typical, as horses suffered a higher casualty rate than their riders, mostly from high-speed collisions, but also from errant sword strokes hitting them in the back of the neck. Every knight was also accompanied by one or more squires, as you see in the background. They carried his provisions, extra lances, etc., but were not allowed to participate in combat against knights. On the other hand, if a common thief or other lower-class villain appeared, only the squire could fight him. Knights were prohibited from fighting non-knights except in self defense.

First published 1508 in Castillian

English translation by Edwin Place and Herbert Behm 1974

Published as Amadis of Gaul: Books I and II

and Amadis of Gaul: Books III and IV

Anyone who has read Don Quixote should recognize the name Amadis of Gaul. He was Quixote's role model as the perfect example of a chivalrous knight-errant. By the time Cervantes wrote his novel, the story of Amadis had been in print in Spanish for over a century, and parts of it in a more primitive form had existed in Spanish and other languages since the 14th century. Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo collected and translated the early Amadis texts--which consisted at the time of three books--modified them and added a fourth book entirely of his own invention. He died in 1504, leaving his Amadis to be published posthumously in 1508.

The story of Amadis takes place at a time several generations before that of King Arthur. There is still a Roman Empire, as well as a Byzantine Empire, but Great Britain, Gaul and Spain are independent kingdoms. The tale begins with the meeting of Amadis's parents, King Perion of Gaul and Princess Elisena of Brittany. They have a secret moonlight tryst, then separate. Elisena becomes pregnant as a result, but manages to hide her condition from her parents. When she gives birth to Amadis, her maid takes the baby, puts him in a boat along with a note, a ring and a sword, and shoves him out to sea. He is found (of course), and reared by foster parents in Scotland who call him just "Child of the Sea." Years later Amadis's parents actually get married, but Elisena doesn't tell her husband about the child she bore and abandoned.

The Child of the Sea, having remarkable good looks, physical prowess and moral rectitude, desires nothing more than to become a knight. He finds a patron in King Lisuarte of Great Britain, and falls madly and permanently in love with the king's daughter Oriana. Just as Amadis is the most perfect knight in the world, Oriana is the most beautiful woman in the world. Amadis goes on one adventure after another, fighting other knights, rescuing captives, slaying giants, and doing battle with a fire-breathing monster. Along the way his parentage is disclosed, he learns his real name, and he finds that he has two brothers--both of them exemplary knights. His travels take him to the shores of Bohemia and the isles of Romania (obviously Montalvo's geography was a little fuzzy) and as far as Constantinople. He is aided from time to time by the mysterious sorceress Urganda the Unknown, and tangles more than once with her arch-enemy Arcalus the Enchanter.

Amadis pines constantly for his lady love, Oriana, who loves him just as much in return. They keep their affections secret from all but their closest friends, but when Fortune gives them a night together they make the most of it. Oriana gets pregnant, secretly bears a son named Esplandian, and in trying to hide him accidentally loses him in the woods where he is nursed by a lioness, then reared by a hermit. He is destined, as we are told many times, to become an even greater knight than Amadis and eventually Emperor of Constantinople.

The overriding theme of Amadis of Gaul is the institution of knight-errantry. A knight is expected to go in search of adventures which will add to his glory and honor. His first duty is to help maidens and matrons in need, but he is also to aid and defend the poor and downtrodden of either gender. He is devoutly religious and displays proper Christian virtues, but he fights for personal glory, not the glory of the Church. He also seeks to be worthy of his lady love, if he should have one. Those knights who do not have a lady are free to enjoy the bed of any willing maiden, but once a knight-errant has fallen in love--even if it is his own secret--he must be true to his lady, no matter how many years it will take him to win her. A knight's martial prowess reflects his moral worth, for God would not have made him strong unless he were good. This leads to a system of justice based on trial by combat. Even a beauty contest is decided by a joust, with the damsel whose champion emerges victorious being crowned most beautiful.

Knights-errant usually go about in full armor with their helmets secured, thus keeping their identity hidden. Inevitably this leads to several accidental battles between brothers, friends, father and son, etc. Amadis especially seems to make a fetish of secrecy, using assumed names on most of his adventures. (One wonders how he expects to earn glory if no one knows who he is.) In this and other respects, knights-errant are the precursors of our modern-day fictional costumed superheroes. In their less noble aspects they resemble Wild West gunfighters.

The first book of Amadis of Gaul consists of a series of loosely connected short adventures, some of which readers of Arthurian legends will easily recognize as having been borrowed from the exploits of Lancelot, Parzival, Tristan and Gawain. The second and third books, however, appear to have been heavily re-written by Montalvo to weave Amadis's adventures and those of his friends and brothers into a larger, more coherent story. The author keeps several quests going at once, shifting scenes to maintain the suspense. In the fourth book, which is Montalvo's own, action is on a much grander scale, as Amadis and Oriana are the focus of a clash of empires.

The novel regularly addresses several moral and emotional dilemmas. Are we obliged to sacrifice our personal honor for the general good or the welfare of our friends? (Amadis refuses to.) What do we do when our personal honor and our duty to our sovereign are at odds? (Amadis puts his pride before his king, and is praised for doing so.) And how do we handle that moment when we realize that we are past our prime and it is time to let the next generation take the spotlight?

The writing in Amadis of Gaul is the least stylized and formulaic of any of the romances of chivalry I have read. This is not to say that it is the best, or that the language is modern, but that the dialog and feelings of the characters are the most natural, and the actions are the most believable. This is especially true of the many combat scenes. Montalvo writes like a man who has been there. Every joust and every battle is distinctly different and filled with believable and vivid detail.

Montalvo followed up his Amadis with a volume called The Exploits of Esplandian (which he shamelessly plugs throughout Book IV). Other writers of various nationalities followed it up with their own sequels until, by Don Quixote's time, the Amadis franchise consisted of at least 24 volumes. The sequels, however, are markedly inferior to the original four books of Montalvo's as Cervantes himself tells us in Don Quixote. The only complete modern English translation is the edition in two volumes by Edwin Place and Herbert Behm, which is the one I am reviewing. It appears to be a very literal translation, preserving the occasional long and ornate phase at the expense of readability. For a work of such size and antiquity, there are surprisingly few explanatory notes or other aids. Robert Southey's 1803 translation is also widely available, but the prudish poet removed the few references to sexual activity and the female body, as well as some moral asides by Montalvo that he thought were boring. Southey's translation was published in three volumes, but it does contain all four original books. Sue Burke is publishing a translation of Amadis of Gaul on her blog in biweekly installments, but is only about half finished. If you want to sample the story, you can do so at http://amadisofgaul.blogspot.com/.

I found Amadis of Gaul to be often entertaining and occasionally moving or suspenseful even though the leading characters, as is typical of medieval romances, are unbelievably perfect. It would certainly be more widely read if it were shorter, but its length of 1400+ pages no doubt has intimidated translators, publishers and readers alike.

"The Knight-errant" by John Everett Millais shows what could be a typical scene from Amadis of Gaul, the rescuing of a damsel in distress. Amadis finds at least one damsel tied to a tree by a would-be rapist, but her state of dress isn't specified. Note that Millais's knight is wearing armor from a period later than Montalvo's. His moon is also impossible--for the crescent to be perpendicular to the horizon the sun would also have to be in the sky.

This painting, "I Am Sir Launcelot du Lake" by N. C. Wyeth, is probably a more accurate depiction of the armor worn by Amadis than the Millais painting. The helmet did not have a hinged visor, so it had to be unlaced and removed to reveal the knight's face. The body was covered mostly by chain mail, with armor plate in the more exposed areas, but this appears to have varied according to the wearer's wealth and taste. The fallen horse in the background is typical, as horses suffered a higher casualty rate than their riders, mostly from high-speed collisions, but also from errant sword strokes hitting them in the back of the neck. Every knight was also accompanied by one or more squires, as you see in the background. They carried his provisions, extra lances, etc., but were not allowed to participate in combat against knights. On the other hand, if a common thief or other lower-class villain appeared, only the squire could fight him. Knights were prohibited from fighting non-knights except in self defense.

28baswood

Great review of Amadis of Gaul. I think I will be one of those readers put off by its length.

Interesting to see those pictures of knights in armour. The Wyeth painting looks much more realistic; the armour actually looks heavy in that picture as it must have been in real life.

Interesting to see those pictures of knights in armour. The Wyeth painting looks much more realistic; the armour actually looks heavy in that picture as it must have been in real life.

29NanaCC

>27 StevenTX: Steven, Your review of Amadis of Gaul is excellent. Very interesting.

30rebeccanyc

I agree with Barry's first paragraph!

32labfs39

Fascinating illustrated review. I wish the knight in Millais' painting would keep his eyes on what he is doing. Lots of potential for inadvertent injuries!

33dchaikin

>27 StevenTX: kudos Steven - great review and congrats for reading the entire thing.

>18 StevenTX: this review of The origin of the Brunists leaves me so curious. How does it tie into the historical Giovanni Bruno, and does it take the freedom of science of approach, the pantheist approach, or some other parallel or not so parallel approach? Might need to keep this one in mind. Good luck with the sequel.

>18 StevenTX: this review of The origin of the Brunists leaves me so curious. How does it tie into the historical Giovanni Bruno, and does it take the freedom of science of approach, the pantheist approach, or some other parallel or not so parallel approach? Might need to keep this one in mind. Good luck with the sequel.

34rebeccanyc

>33 dchaikin: Dan, I think the historical person was Giordano Bruno, not Giovanni, but the parallel of names is interesting.

35StevenTX

>33 dchaikin: - I'm sure you were thinking of Giordano Bruno, as Rebecca said, but the association of the two by readers is inevitable, therefore it has to be considered an intentional choice by the author. There is also the fact that Giovanni Bruno is the Italian equivalent of John Brown, another historical martyr figure. And there are a number of aspects to Bruno's experience which parallel that of Christ, such as the fact that he was entombed for three days before being rescued and "rising from the dead." What I think Coover is doing is showing how we construct meaning out of cultural association, even to the point of redirecting our lives on the basis of what is actually only a coincidence. There is one example after another in the book where people who are looking for spiritual direction find "signs" in ordinary or random events that they have just chosen to interpret as pointing them in the direction they already wanted to go.

I'm not sure if that answers your question about the author's approach. Here again, what we take from the book depends on what we brought with us. I see it as a satire of all religions, but a Baptists might come away with the message to "beware false prophets," while a Catholic just sees that those crazy Protestants are at it again. From the little I've read of the sequel, however, it appears to be a broader and more vicious satire of religion in general--but it's too early to be sure.

I'm not sure if that answers your question about the author's approach. Here again, what we take from the book depends on what we brought with us. I see it as a satire of all religions, but a Baptists might come away with the message to "beware false prophets," while a Catholic just sees that those crazy Protestants are at it again. From the little I've read of the sequel, however, it appears to be a broader and more vicious satire of religion in general--but it's too early to be sure.

36SassyLassy

>27 StevenTX: Great review, putting the book in context.

How did you learn about armour?

On another note, I would agree that Coover is satirizing belief, but I also found a strong association between the subjects of his satire and the less advantaged of the town. That just made the line about the poor being always among us pop into my head. Coover certainly wasn't a hopeful writer. No wonder the townspeople were looking for signs of a better life!

How did you learn about armour?

On another note, I would agree that Coover is satirizing belief, but I also found a strong association between the subjects of his satire and the less advantaged of the town. That just made the line about the poor being always among us pop into my head. Coover certainly wasn't a hopeful writer. No wonder the townspeople were looking for signs of a better life!

37StevenTX

Sex! The Punctuation Mark of Life by Lucretia Torva

First published 2014

Review of an ARC provided via NetGalley

Sex! The Punctuation Mark of Life is an autobiographical work focusing entirely on the author's sex life. Its purpose is to present "real stories with real men, and women... not some made up fantasy that is highly improbable," to demonstrate that sex is not only fun, but is important to our physical, emotional and spiritual health. She condemns the "puritan, or guilt-ridden point of view" that only "leads to more perversions and addictions." The stories are taken from her own life, are presented in chronological order, and appear to have been fictionalized only to the point of disguising the identities of Torva's sex partners.

The stories span the author's entire adult life from age 18 to the very recent past (she is now in her 50s). Most of the episodes deal with her first experience with a particular sex act or combination of partners, including bisexuality and group sex, and are quite explicit. Romance is noticeably absent. With only a single exception, her encounters are with casual acquaintances or, more recently, with men and women whom she meets via the Adult FriendFinder dating service. She limits herself to one or two meetings with any single partner to avoid stale, long-term attachments. Torva promotes sex as a form of recreation like bridge or tennis, not as the culmination of a love affair.

Unfortunately the author's message is clouded by some of the few details she gives us about her life outside of the bedroom. She had two failed marriages followed by a long period of dependency on anti-depressants. She needs alcohol to release her inhibitions before having sex, and not long ago was celibate by choice for several years. These admissions seem to contradict her claim that an adventurous sex life has brought her emotional and spiritual well-being, or at least to beg for further explanation. Still, she makes a good point when she says "I feel that I need to be uncomfortable with regularity whether it's about sex or business or art or whatever. I don't grow without being uncomfortable."

The language in which the book is written is youthful, casual and conversational. Interjections like "Tee hee!" and "Yum!" aren't to my taste, but some readers will enjoy them. What I found more objectionable is that the author includes only her adventures where everything goes perfectly, so while these may be "real stories" they aren't all that different from the "made up fantasy" of flawless bodies and uninhibited pleasure typical of most erotic fiction. Getting drunk and going off to have sex with a stranger, as she does more than once, is also not a wise thing for a woman to do. So while this book's ideal audience may be a young person who needs some erotic instruction or a pep talk on getting the most out of his or her sex life, it could lead both to inflated expectations and risk-taking if taken too seriously. The author's claims regarding the therapeutic value of recreational sex may be true, but her memoir is best treated as erotic entertainment only.

First published 2014

Review of an ARC provided via NetGalley

Sex! The Punctuation Mark of Life is an autobiographical work focusing entirely on the author's sex life. Its purpose is to present "real stories with real men, and women... not some made up fantasy that is highly improbable," to demonstrate that sex is not only fun, but is important to our physical, emotional and spiritual health. She condemns the "puritan, or guilt-ridden point of view" that only "leads to more perversions and addictions." The stories are taken from her own life, are presented in chronological order, and appear to have been fictionalized only to the point of disguising the identities of Torva's sex partners.

The stories span the author's entire adult life from age 18 to the very recent past (she is now in her 50s). Most of the episodes deal with her first experience with a particular sex act or combination of partners, including bisexuality and group sex, and are quite explicit. Romance is noticeably absent. With only a single exception, her encounters are with casual acquaintances or, more recently, with men and women whom she meets via the Adult FriendFinder dating service. She limits herself to one or two meetings with any single partner to avoid stale, long-term attachments. Torva promotes sex as a form of recreation like bridge or tennis, not as the culmination of a love affair.

Unfortunately the author's message is clouded by some of the few details she gives us about her life outside of the bedroom. She had two failed marriages followed by a long period of dependency on anti-depressants. She needs alcohol to release her inhibitions before having sex, and not long ago was celibate by choice for several years. These admissions seem to contradict her claim that an adventurous sex life has brought her emotional and spiritual well-being, or at least to beg for further explanation. Still, she makes a good point when she says "I feel that I need to be uncomfortable with regularity whether it's about sex or business or art or whatever. I don't grow without being uncomfortable."

The language in which the book is written is youthful, casual and conversational. Interjections like "Tee hee!" and "Yum!" aren't to my taste, but some readers will enjoy them. What I found more objectionable is that the author includes only her adventures where everything goes perfectly, so while these may be "real stories" they aren't all that different from the "made up fantasy" of flawless bodies and uninhibited pleasure typical of most erotic fiction. Getting drunk and going off to have sex with a stranger, as she does more than once, is also not a wise thing for a woman to do. So while this book's ideal audience may be a young person who needs some erotic instruction or a pep talk on getting the most out of his or her sex life, it could lead both to inflated expectations and risk-taking if taken too seriously. The author's claims regarding the therapeutic value of recreational sex may be true, but her memoir is best treated as erotic entertainment only.

38LolaWalser

Interjections like "Tee hee!" and "Yum!"

Bleargh! Urgh! Yuck!

(teheeheehee...)

That book sounds like it demonstrates the opposite of what the author intended. And that, at least, is funny.

Bleargh! Urgh! Yuck!

(teheeheehee...)

That book sounds like it demonstrates the opposite of what the author intended. And that, at least, is funny.

39StevenTX

>36 SassyLassy: - How did you learn about armour?

I'm no expert on the subject--there's just a lot of realistic detail in Amadis of Gaul. For example, the knight's shield was actually hung from his neck with a sling, not just held in his hand, and his sword was attached to his wrist with a lanyard. Both of these were so he could retrieve them if they were knocked from his grasp while on horseback.

One of the most memorable scenes was a large battle in which eager, undisciplined knights in the rear ranks kept pushing forward until the opposing front lines were so crammed together that there was no room to swing a sword. All the knights on the front line could do was grapple the enemy by hand and try not to be crushed or thrown to the ground. Montalvo says that they were in far more danger of being trampled to death by their own side than of being killed by the enemy. John Keegan's landmark study The Face of Battle describes just such scenes from medieval warfare, which tells me that Montalvo was a man who had participated in knightly combat himself and whose descriptions can be trusted.

Thanks for your comment about Coover's view of the lower classes. His sympathetic look at poverty and the despair of unemployment is yet another aspect to the novel that makes it worth reading. The sequel seems less sympathetic (so far, at least). Many of the Brunists seem to be more dimwitted than disadvantaged.

I'm no expert on the subject--there's just a lot of realistic detail in Amadis of Gaul. For example, the knight's shield was actually hung from his neck with a sling, not just held in his hand, and his sword was attached to his wrist with a lanyard. Both of these were so he could retrieve them if they were knocked from his grasp while on horseback.

One of the most memorable scenes was a large battle in which eager, undisciplined knights in the rear ranks kept pushing forward until the opposing front lines were so crammed together that there was no room to swing a sword. All the knights on the front line could do was grapple the enemy by hand and try not to be crushed or thrown to the ground. Montalvo says that they were in far more danger of being trampled to death by their own side than of being killed by the enemy. John Keegan's landmark study The Face of Battle describes just such scenes from medieval warfare, which tells me that Montalvo was a man who had participated in knightly combat himself and whose descriptions can be trusted.

Thanks for your comment about Coover's view of the lower classes. His sympathetic look at poverty and the despair of unemployment is yet another aspect to the novel that makes it worth reading. The sequel seems less sympathetic (so far, at least). Many of the Brunists seem to be more dimwitted than disadvantaged.

40labfs39

>39 StevenTX: very interesting. Although I doubt I will ever read Amadis of Gaul, The Face of Battle seems within the realm of possibility. Whether I do or not, I always learn something from your thread, Steven. Thanks

41StevenTX

Skinswaps by Andrej Blatnik

First published in Slovenian 1990

English translation by Tamara Soban 1998

Skinswaps is a collection of short stories, most of them using skin as a motif and often as a metaphor for identity. The stories have various settings, including the author's native Slovenia which, at the time of his writing, was still a part of Yugoslavia but had a growing independence movement. Political themes are obvious in several of the stories.

In the chilling story "His Mommy's Voice," a boy sees a horror movie in which a killer deceives a child by pretending to be its mother. Coming home from the movie, the boy becomes convinced that his mother is an enemy in disguise. It isn't difficult to warp the innocent so that they fear what they should love and love what they should fear.

Several stories, like "Two," are abstract and metafictional. "I can feel the animal lick my hand hanging over the side of the bed," the narrator begins, but does it exist? Does it exist only because he is thinking of it? Does the animal want him to keep on thinking of it until it is strong enough to kill him? Or is the animal thinking up the narrator too?

Other selections are about people who have walled themselves off from social and interpersonal relations, retreating into the private shells of their skins. In "Actually" it is a writer who has withdrawn into his writing to the extent that everything that happens to him in real life is immediately transposed into a story he is writing. He never moves from his desk, typing every word he speaks or that is spoken to him as it is being spoken.

Perhaps the most disturbing story is "The Taste of Blood," which deals with the aftermath of violence and oppression when any uniform is something to fear. A lonely young woman named Katarina comes upon the body of a drowned girl on a riverbank as two policemen are waiting for the hearse to remove it. Katarina is fascinated by the sight. The policemen tease her, then proceed to making sexual advances and threats. Not long ago, policemen such as these had killed her father. They laugh and reassure her that they mean her no harm, but can she believe them? Does she even want them to be bluffing? Or has the taste of blood entered her system to where she needs violence and coercion?

Skinswaps is an excellent collection with a mix of settings, moods and themes. Though most of the stories are darkly ironic, there is enough humor mixed in to provide relief when it is needed.

First published in Slovenian 1990

English translation by Tamara Soban 1998

Skinswaps is a collection of short stories, most of them using skin as a motif and often as a metaphor for identity. The stories have various settings, including the author's native Slovenia which, at the time of his writing, was still a part of Yugoslavia but had a growing independence movement. Political themes are obvious in several of the stories.

In the chilling story "His Mommy's Voice," a boy sees a horror movie in which a killer deceives a child by pretending to be its mother. Coming home from the movie, the boy becomes convinced that his mother is an enemy in disguise. It isn't difficult to warp the innocent so that they fear what they should love and love what they should fear.

Several stories, like "Two," are abstract and metafictional. "I can feel the animal lick my hand hanging over the side of the bed," the narrator begins, but does it exist? Does it exist only because he is thinking of it? Does the animal want him to keep on thinking of it until it is strong enough to kill him? Or is the animal thinking up the narrator too?

Other selections are about people who have walled themselves off from social and interpersonal relations, retreating into the private shells of their skins. In "Actually" it is a writer who has withdrawn into his writing to the extent that everything that happens to him in real life is immediately transposed into a story he is writing. He never moves from his desk, typing every word he speaks or that is spoken to him as it is being spoken.

Perhaps the most disturbing story is "The Taste of Blood," which deals with the aftermath of violence and oppression when any uniform is something to fear. A lonely young woman named Katarina comes upon the body of a drowned girl on a riverbank as two policemen are waiting for the hearse to remove it. Katarina is fascinated by the sight. The policemen tease her, then proceed to making sexual advances and threats. Not long ago, policemen such as these had killed her father. They laugh and reassure her that they mean her no harm, but can she believe them? Does she even want them to be bluffing? Or has the taste of blood entered her system to where she needs violence and coercion?

Skinswaps is an excellent collection with a mix of settings, moods and themes. Though most of the stories are darkly ironic, there is enough humor mixed in to provide relief when it is needed.

42labfs39

I was curious as to how you came across this title, and looked up the publisher. I got all excited when I saw that it was part of a series called Writings from an Unbound Europe. Sadly, I then read the following in a blog entry by Chad Post at Three Percent:

The editors of Northwestern University Press have decided to end the run of Writings from an Unbound Europe, the only more or less comprehensive book series devoted to translated contemporary literature from the former communist countries of Eastern/Central Europe. The final title in the series, the novel Sailing Against the Wind (Vastutuulelaev) by the Estonian Jaan Kross (1920-2007) will appear in a translation by Eric Dickens some time in 2012. With that title Unbound Europe will have published 61 books since its inception in 1993. Among the highlights of what has been published over this twenty-year period are the first English-language editions of David Albahari, Ferenc Barnas, Petra Hůlová, Drago Jančar, Anzhelina Polonskaya, and Goce Smilevski. By far the best selling title in the series is Death and the Dervish (Drviš i smrt) by the Bosnian writer Meša Selimović (1910-1982), which has sold close to 6000 copies since it appeared in 1996. In recent years, however, changes in book-buying habits and diminished interest in Eastern/Central Europe in the English speaking world have led to significantly lower sales, even for masterpieces by such major writers as Borislav Pekić and Bohumil Hrabal. I would like to thank the series co-editors Clare Cavanagh, Michael Henry Heim, Roman Koropeckyj, and Ilya Kutik as well as several generations of Northwestern University Press editors and directors for their work on this project. Most of the books published in the series remain in print and will continue to be available on the Northwestern University Press backlist.

Andrew Wachtel

General Editor

It's such a shame that translated fiction gets such short shrift in the US.

Nevertheless, I will start looking for titles in this series.

The editors of Northwestern University Press have decided to end the run of Writings from an Unbound Europe, the only more or less comprehensive book series devoted to translated contemporary literature from the former communist countries of Eastern/Central Europe. The final title in the series, the novel Sailing Against the Wind (Vastutuulelaev) by the Estonian Jaan Kross (1920-2007) will appear in a translation by Eric Dickens some time in 2012. With that title Unbound Europe will have published 61 books since its inception in 1993. Among the highlights of what has been published over this twenty-year period are the first English-language editions of David Albahari, Ferenc Barnas, Petra Hůlová, Drago Jančar, Anzhelina Polonskaya, and Goce Smilevski. By far the best selling title in the series is Death and the Dervish (Drviš i smrt) by the Bosnian writer Meša Selimović (1910-1982), which has sold close to 6000 copies since it appeared in 1996. In recent years, however, changes in book-buying habits and diminished interest in Eastern/Central Europe in the English speaking world have led to significantly lower sales, even for masterpieces by such major writers as Borislav Pekić and Bohumil Hrabal. I would like to thank the series co-editors Clare Cavanagh, Michael Henry Heim, Roman Koropeckyj, and Ilya Kutik as well as several generations of Northwestern University Press editors and directors for their work on this project. Most of the books published in the series remain in print and will continue to be available on the Northwestern University Press backlist.

Andrew Wachtel

General Editor

It's such a shame that translated fiction gets such short shrift in the US.

Nevertheless, I will start looking for titles in this series.

43StevenTX

>42 labfs39: That's a shame about the Writings from an Unbound Europe. I've read several in that series and have a few more on the shelf I haven't gotten to yet.

I should probably explain why I read this book now when it isn't related to any of my current reading themes. I actually bought it more than a year ago when Reading Globally was doing a theme on Eastern Europe, but I didn't get to it before the quarter ended. Then, earlier this month, I joined NetGalley and saw a new book by Blatnik listed, a collection of stories titled Law of Desire. I put in for it and got it, but I decided to read his earlier work first as background. Law of Desire will be published in August by Dalkey Archive as part of their Slovenian Literature Series, which has nine titles so far.

I should probably explain why I read this book now when it isn't related to any of my current reading themes. I actually bought it more than a year ago when Reading Globally was doing a theme on Eastern Europe, but I didn't get to it before the quarter ended. Then, earlier this month, I joined NetGalley and saw a new book by Blatnik listed, a collection of stories titled Law of Desire. I put in for it and got it, but I decided to read his earlier work first as background. Law of Desire will be published in August by Dalkey Archive as part of their Slovenian Literature Series, which has nine titles so far.

44baswood

Sex! The punctuation mark of life. Are you sure NetGalley is such a good idea.

45StevenTX

>44 baswood: - Are you sure NetGalley is such a good idea.

I'm just going to be more selective from now on. After all, look at the other books I've reviewed or received: Fear: A Novel of World War I, The Brunist Day of Wrath, and most recently three books from Dalkey Archive Press.

I'm just going to be more selective from now on. After all, look at the other books I've reviewed or received: Fear: A Novel of World War I, The Brunist Day of Wrath, and most recently three books from Dalkey Archive Press.

46labfs39

I wish I read on a device. It sounds as though you are able to find some real gems and from interesting presses too.

47StevenTX

>46 labfs39: I wish I read on a device.

I just happened to notice today that Kindles are on sale for Mothers Day. The Paperwhite, their best e-reader model, is just $99.

I just happened to notice today that Kindles are on sale for Mothers Day. The Paperwhite, their best e-reader model, is just $99.

48labfs39

I'm tempted. Yet I am still so fond of possessing the books I read that I fear I would want to then buy in paper those books that I read and enjoyed electronically. Also, my desire to read e-books is mostly because of the availability of free and inexpensive versions, which contradicts my desire to support and help sustain the publication of paper books, especially those in translation, and bookstores.

49rebeccanyc

>42 labfs39: >43 StevenTX: I see that I have two unread titles from the Writings from an Unbound Europe series (one of them the best-selling Death and the Dervish), but the whole series sounds intriguing. How disappointing that they're discontinuing it.

50edwinbcn

Wonderful review of Amadis of Gaul.

52StevenTX

Law of Desire: Stories by Andrej Blatnik

First published in Slovenian 2000

English translation 2014 by Tamara M. Soban

Review of an ARC provided via NetGalley

Law of Desire is a collection of fifteen short stories about people struggling to understand and communicate their needs and wants. The settings are typically modern, some of them in regions of recent conflict such as the war-torn countries of the former Yugoslavia, others in the United States or unspecified urban locations. The characters are typically troubled and insecure, often wanting nothing more than to be understood, but finding it the most difficult of all to obtain.

In "What We Talk About," a young man and woman are attracted to each other, but their relationship can't get past their awkward fumbling for something to talk about.

"When Marta's Son Returned" describes a mother's frustration in trying to break her son out of the shell into which he has withdrawn since returning from a war. She finally uses music to get him to talk, but what he says leads her to a conclusion that is a gut-wrenching and unexpected statement about war and society.

"Electric Guitar" takes us inside the mind of an abused child whose father is trying for force him to learn the accordion. His attempts are hopeless, but while he is being punished for his failures he secretly dreams of playing an electric guitar. (The electric guitar is a motif in several of the stories in the collection.)

In the chilling "Letter to Father" the protagonist is not a single character, but Mankind itself writing a letter to its god: "Father. Are you there? Are you listening? I'm tired, Father. I can't tell your stories any more. I've forgotten my own."

And in "Just As Well," a man comes home early to find his wife in bed with his best friend. He can't decide whether to shoot his friend, his wife, or himself. None of his options is good, but things can't just go back to the way they were, can they?

Blatnik's stories range in mood from dark comedy to bitter irony. Among other things, they demonstrate how our failure to achieve our desires is often because of the obstacles modern life seems to throw in the way of simple communication.

First published in Slovenian 2000

English translation 2014 by Tamara M. Soban

Review of an ARC provided via NetGalley