Este tema está marcado actualmente como "inactivo"—el último mensaje es de hace más de 90 días. Puedes reactivarlo escribiendo una respuesta.

1rebeccanyc

My review.

This novel, the story of the rise and fall of Gervaise Coupeau, is so compelling I could barely put it down, even as there were times I wanted to slap Gervaise and ask her what on earth she was thinking and even though Zola can be didactic at times about his thesis that susceptibility to alcoholism is passed down from generation to generation and eventually inevitably leads to a downfall. Zola's goal with this book was to depict the people and the world of the new industrial working class living in slummy areas in what were then the suburbs of Paris.

We meet Gervaise when she has moved to Paris with Lantier, the father of her two children (one is Etienne in Germinal and the other is Claude of The Masterpiece); a laundress back in the provinces, she gets a job working in a laundry and it is there that she learns Lantier has left her for another woman, taking their meager possessions with him. Eventually, she succumbs to the pleadings of Coupeau, a roofer, to marry him, because she believes he is a hard-working, nondrininking man, who will help her achieve her goal of being able to "work, put food on your table, have a little place of your own, bring up your kids, and die in your own bed." (p. 42) Things go well at first: they have a daughter, Nana (who will have a book of her own) and save enough so Gervaise can achieve her goal of opening her own laundry (although, in the end, a harbinger of bad times to come, Gervaise has to borrow money from a sweet, but apparently slightly dimwitted, metalsmith, Goujet, who has a crush on her to be able to start the business). Again, things go well for a while, but then they don't. In the second half of the novel, we witness Gervaise's slow but inevitable slide into debt, self-indulgence, sloth, and ultimately drinking and despair, helped along the way by Coupeau, who spends his days and nights drinking, and by Lantier, who reappears, integrates himself into the neighborhood and their home, and who not only is always looking out for himself but also always does so at the expense of others.

This is just a broad outline of the plot. Zola peoples the novel and the neighborhood with dozens of other characters, many vividly drawn, others more walk-ons, and the neighborhood itself is equally a character in the novel. People live on top of each other, everyone knows everyone's business (or thinks they do), the sights and sounds and perhaps above all the smells are pervasive, and there are bars all over. Zola's genius is to relate all these people to each other and to reflect aspects of Gervaise's story in other subplots and characters. He also creates some dramatic set pieces in the Coupeau wedding party's trip to the Louvre, Gervaise's saint's day dinner, and a scene in an insane asylum. There is both depth and breadth in this novel; in some ways, Gervaise's rise and fall is reflected in the different places in which she lives, and her desire for cleanliness, depicted by her work and by her admiration of Goujet's mother's apartment, eventually succumbs to dirt and filth.

One other aspect of this novel, which created quite a stir when it was written, is that a great deal of it is written in working class French slang, some of it said to be arcane. This has has apparently been a challenge to translators; the translator of the Oxford World's Classics edition I read, Margaret Mauldon, has used working class British slang presumably from the same period. Most of this is understandable from the context. There are also lots of sexual double entendres, which also seems to have shocked the literary establishment.

Zola was criticized by both the right and the left for his portrayal of the working class: the right thought him a socialist, the left thought his depiction of the working class demeaning. His plan always was to make Germinal his novel about politics and the working class, and this novel was supposed to be their portrait. It is indeed a vivid one.

PS The picture on the cover of my edition shows a woman with dark hair; Zola makes it clear Gervaise was a blonde.

This novel, the story of the rise and fall of Gervaise Coupeau, is so compelling I could barely put it down, even as there were times I wanted to slap Gervaise and ask her what on earth she was thinking and even though Zola can be didactic at times about his thesis that susceptibility to alcoholism is passed down from generation to generation and eventually inevitably leads to a downfall. Zola's goal with this book was to depict the people and the world of the new industrial working class living in slummy areas in what were then the suburbs of Paris.

We meet Gervaise when she has moved to Paris with Lantier, the father of her two children (one is Etienne in Germinal and the other is Claude of The Masterpiece); a laundress back in the provinces, she gets a job working in a laundry and it is there that she learns Lantier has left her for another woman, taking their meager possessions with him. Eventually, she succumbs to the pleadings of Coupeau, a roofer, to marry him, because she believes he is a hard-working, nondrininking man, who will help her achieve her goal of being able to "work, put food on your table, have a little place of your own, bring up your kids, and die in your own bed." (p. 42) Things go well at first: they have a daughter, Nana (who will have a book of her own) and save enough so Gervaise can achieve her goal of opening her own laundry (although, in the end, a harbinger of bad times to come, Gervaise has to borrow money from a sweet, but apparently slightly dimwitted, metalsmith, Goujet, who has a crush on her to be able to start the business). Again, things go well for a while, but then they don't. In the second half of the novel, we witness Gervaise's slow but inevitable slide into debt, self-indulgence, sloth, and ultimately drinking and despair, helped along the way by Coupeau, who spends his days and nights drinking, and by Lantier, who reappears, integrates himself into the neighborhood and their home, and who not only is always looking out for himself but also always does so at the expense of others.

This is just a broad outline of the plot. Zola peoples the novel and the neighborhood with dozens of other characters, many vividly drawn, others more walk-ons, and the neighborhood itself is equally a character in the novel. People live on top of each other, everyone knows everyone's business (or thinks they do), the sights and sounds and perhaps above all the smells are pervasive, and there are bars all over. Zola's genius is to relate all these people to each other and to reflect aspects of Gervaise's story in other subplots and characters. He also creates some dramatic set pieces in the Coupeau wedding party's trip to the Louvre, Gervaise's saint's day dinner, and a scene in an insane asylum. There is both depth and breadth in this novel; in some ways, Gervaise's rise and fall is reflected in the different places in which she lives, and her desire for cleanliness, depicted by her work and by her admiration of Goujet's mother's apartment, eventually succumbs to dirt and filth.

One other aspect of this novel, which created quite a stir when it was written, is that a great deal of it is written in working class French slang, some of it said to be arcane. This has has apparently been a challenge to translators; the translator of the Oxford World's Classics edition I read, Margaret Mauldon, has used working class British slang presumably from the same period. Most of this is understandable from the context. There are also lots of sexual double entendres, which also seems to have shocked the literary establishment.

Zola was criticized by both the right and the left for his portrayal of the working class: the right thought him a socialist, the left thought his depiction of the working class demeaning. His plan always was to make Germinal his novel about politics and the working class, and this novel was supposed to be their portrait. It is indeed a vivid one.

PS The picture on the cover of my edition shows a woman with dark hair; Zola makes it clear Gervaise was a blonde.

2lriley

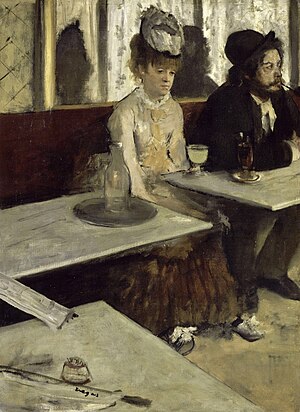

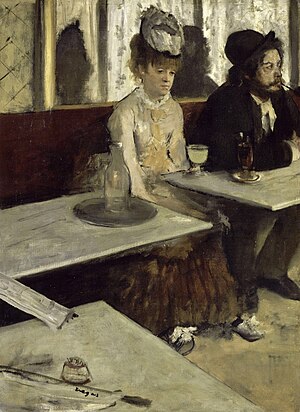

My cover is of a painting called L'absinthe by someone named Edgar--apparently it's in the Louvre. The scene in the insane asylum which more or less ends the novel is quite compelling. An advanced state of the DT's where the sufferer can't stop running.

I don't know if I've reviewed the book or not. I may have. It's been a long time since I've read it though--thinking maybe 10 years. It was one of the first books of his I read--the first I remember was Germinal.

I don't know if I've reviewed the book or not. I may have. It's been a long time since I've read it though--thinking maybe 10 years. It was one of the first books of his I read--the first I remember was Germinal.

3rebeccanyc

The L'absinthe painting I found on Google is by Edgar Degas. Is this the one on your cover?

It's a little more genteel than the way I envision the bar they frequent in L'assommoir.

It's a little more genteel than the way I envision the bar they frequent in L'assommoir.

4lriley

Funny in a way--I was like Edgar?--who?--and it looks very much in the style of Degas now that you got to the bottom of it. The cover is a fragment of the above painting--you see the man, woman, the glass of absinthe--otherwise known as the 'green fairy'--the part missing is the bottle and the second table.

5kesbooks

>3 rebeccanyc: this is the picture on the cover of my Penguin Classic copy of L'assommoir and was the first Emile Zola I read, exactly one year ago. I like your review, rebeccanyc.

I think Zola is an amazing writer, I don't feel like I am reading fiction when I read his books, it feels like he is telling me the truth.

I was captivated by Gervaise and I definitely related to the potential 'to let it all slide'. Luckily I am living in a relatively prosperous environment with supportive loved-ones.

I would love it if L'assommoir was made into a musical/movie like "Les Miserable".

I think Zola is an amazing writer, I don't feel like I am reading fiction when I read his books, it feels like he is telling me the truth.

I was captivated by Gervaise and I definitely related to the potential 'to let it all slide'. Luckily I am living in a relatively prosperous environment with supportive loved-ones.

I would love it if L'assommoir was made into a musical/movie like "Les Miserable".

6rebeccanyc

I was quite fond of Gervaise too and, as with Nana, I just wanted to slap her sometimes and tell her to shape up!

7kesbooks

It is interesting that we want to whisper in these characters ears and say something encouraging like, "come on, you can do it. Live a better life than this". However deep down we can feel the strain that poverty and the living conditions described in these books (whether any reader has every lived in these conditions its irrelevant because Zola and so many others have managed to describe life in these times so well). Seriously can you say you would be able to do anything different than say 'lose yourself in cheap wine' or 'inappropriate love'?

8jfetting

I found Gervaise to be a frustrating character, because I did like her quite a bit and didn't like seeing Lantier and Coupeau walk all over her and take her money. She should have run off to Belgium with Goujet when she had the chance!

>7 kesbooks: Great comment, and very true. I have a bad habit of talking out loud to the books I'm reading, and I found myself multiple times saying "Come on! Don't do that! You know how these things turn out!".

>7 kesbooks: Great comment, and very true. I have a bad habit of talking out loud to the books I'm reading, and I found myself multiple times saying "Come on! Don't do that! You know how these things turn out!".