Simon GarfieldEntrevista

Autor de Es mi tipo

Entrevista con el autor

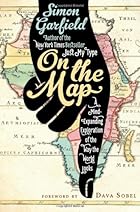

Simon Garfield is a journalist and author whose books include Just My Type: A Book About Fonts and Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color that Changed the World. His latest book is On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks, out this month from Gotham Books.

Simon Garfield is a journalist and author whose books include Just My Type: A Book About Fonts and Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color that Changed the World. His latest book is On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks, out this month from Gotham Books.

I'm going to begin by asking you the first question I asked Ken Jennings when I talked to him about his book Maphead: so what is it about maps, anyway? Why are so many people so fascinated by them?

Maps have helped define what makes us human. Maps were one of the earliest forms of communication, almost certainly existing before language and speech. I'm inclined to agree with Richard Dawkins when he suggests that our ability to draw maps—to show fellow hunters where the juicy elk were—was a key factor in expanding the size of our brains, enabling the leap from apes to homo-sapiens. Beyond all this, maps are frequently beautiful artifacts, telling the best stories in a direct way. The idea of the book was to retell the best of these stories. And occasionally, of course, maps just help us get from A to B.

What first got you interested in maps, and when?

I first got hooked as a boy travelling on the London Underground at the age of 10. The famous Harry Beck tube map—now copied all over the world—was in every carriage and platform. I didn't realize its significance (geographically it's incredibly inaccurate, but as a diagram it's a great piece of information engineering), but I was entranced by the names on it and its possibilities. The prospect of travelling to the end of any of the lines—Amersham at the end of the Metropolitan line, say—seemed as exotic and far away as Antarctica. I've collected tube maps ever since, and now framed copies line my hallway at home.

You've got a collection of early maps, I understand? What's the acquisition you're most proud of?

Apart from a 1908 London Underground Map? Probably a 19th century map of St Ives in Cornwall before it became a tourist attraction. Those surfing beaches sure look empty ...

Of all the maps you got to look at during the research process for your book, which was the strangest?

That would be maps featuring the Mountains of Kong. This was a range that stretched like a belt from the west coast of Africa through half the continent, and featured on world maps and atlases for almost the whole of the 19th century. The mountains were first sketched in 1798 by the highly regarded English cartographer James Rennell, a man already famous for mapping large parts of India. The problem was, he had relied on erroneous reports from short-sighted explorers and his own imagined distant sightings. The Mountains of Kong didn't actually exist, but like an unreliable Wikipedia entry that appears in a million college essays, the mythical range was reproduced on maps by other mappers for more almost a century, until an enterprising Frenchman actually travelled there in 1889 and found that there were hardly even any hills. But they still featured in a Rand McNally map of India in 1890 ...

I also really like a very straightforward map of London on the Internet by a character called Nad. It's a watercolour painted about a decade ago, featuring an oval, the Thames twisting through it, and a small red bulbous area around Kensington and Mayfair marked 'Very Rich'. The whole of the rest of London is simply marked 'Losers'. Humour, politics and simplification in one map—perfect.

What single thing that you learned as you researched On the Map surprised you the most?

What single thing that you learned as you researched On the Map surprised you the most?

Partly it was how much we got wrong about the world as we drew our maps (the Mountains of Kong are only the start of it; there once were more than 120 mapped islands in the Pacific that weren't really there), but partly I was surprised about how much we got right. The maps of the world from the Great Library of Alexandria more than 2000 years ago are remarkable things. Only three continents, but their shapes are very good, and the map makers certainly knew the world was roundish.

A few chapters in On the Map touch on the mistakes that periodically crop up on maps, and sometimes stick around for a while. Obviously each case is different, but give us a couple of examples of how these mistakes happen, and why do you think so many of them are so long-lived?

Well I really should have read all these questions through before I started writing, shouldn't I? But I can certainly comment on the most recent and famous of these mistakes: Apple Maps. How the biggest tech company in the world could get this so wrong is extraordinary, and it took them a week to admit that they'd goofed. Maps and location are the single most important features of phones apart from making calls, and I'm sure it's something Steve Jobs would never have let out the door. The best comment I heard was a tweet: 'I wouldn't trade my Apple Maps for all the tea in Cuba'. I write this on the day when Google have released Google Maps as an app—thank God. (That's God and Dawkins in one questionnaire I hope you realize.)

What's your home library like? What sorts of books would we find on your shelves?

I do like the term 'library'—for me that always suggests leather and ladders and reading rooms. My real library is the London Library, which I pretty much use as an office these days, one of the best membership lending libraries in the world. My bookshelves at home have just thanked me recently for a slight purge, as they were groaning. I have all the books I've bought to help me with my last 14 books, many books sent to me for review, and then my personal choices, which tend to be 70 percent non-fiction and 30 percent novels and poetry. I'm reading a lot of nature and travel writing at the moment.

What have you read and enjoyed recently?

Two books I've loved of late: Walking Home by Simon Armitage, a funny account of a soggy walk across the Pennine Way from Derbyshire to Scotland, reading poetry at some unlikely venues en route to pay his way. And an oldie but goodie: 84 Charing Cross Road by Helene Hanff, the classic epistolary account of a tough American lady's relationship with a London bookshop and its staff (and its books).

Can you tell us a bit about your next project?

The last choice gives it away: I'm working on a book about letters.

—interview by Jeremy Dibbell